On September 20, the day The Broad opened in Los Angeles, I waited in line 45 minutes to spend 45 seconds (strictly timed on a docent’s iPad) in Yayoi Kusama’s “Infinity Mirrored Room — The Souls of Millions of Light Years Away” (2013). A lot of other people had to wait even longer, so I counted myself fortunate. Still, 45 minutes in a slow-creeping line is time enough to ponder whether an experience is worth waiting for. My conclusion, after biding my allotment inside this vaunted, would-be visual Orgasmatron, was that it wasn’t. I was underwhelmed by the LED-and-mirrors shtick, which struck me not as mystical, but chintzy. During the moments when the door opened and closed and light bled in from the hallway, the glamor was unmasked as low-tech and resolutely un-woo-woo. You could see dust in the air and fingerprints on the mirrors. You could see the water surrounding the viewing plank, looking very much like a kiddie pool. It recalled “It’s a Small World” at Disneyland, except without the boat and with a slightly shorter line.

As much as I’d hoped this immersive environment would indeed transport me millions of light years away, I found myself transported instead into one of those cheesy stretch limousines with fiber-optic moon-roofs. Or to a place back in Portland called Tub And Tan, where you can rent a rather stunningly garish room appointed with green laser-lights fanning out through pumped-in mist, a sound system with 100 channels of music, and a disco ball spinning in the glint of colored lights. There’s a hot tub, too. The “Infinity Room” doesn’t have one of those.

But of course, a Disney ride, a stretch limo, and a hot tub by the hour aren’t art installations, and while their appeals may include irony, post-irony and kitsch, they are not intended as critiques thereof in the ways we’ve become inured to in the echelons of contemporary art. What exactly separates a Kusama installation from a theme-park attraction — or a Jeff Koons porcelain sculpture from a Hummel figurine — is the sort of quandary that has filled art-theory epistles for more than a century now. And at this late date, not only are there no definitive answers to such questions, there also aren’t any criteria to establish the parameters of the questions to begin with. It does seem increasingly evident, however, that the process of supplanting sincerity of intent with irony and critique has exponentially leeched our collective sense of the primacy of the artist’s commitment, which much of pre-Modernist art in the West aimed to evoke. It may still be found, though, in realms outside (notice I do not say “beneath”) the art world.

Every September, when the Portland Institute for Contemporary Art’s Time-Based Art Festival (TBA) rolls around, I hear it repeated in circles both tony and pedestrian that much of what passes for performance art at TBA could not hold a proverbial candle to the less rarefied but arguably more committed performances taking place nearby in the city’s storied burlesque clubs. One type of social practice exists under the rubric of art, the other under the mantle of entertainment, but those labels no longer plot either’s place on a continuum of high to low. In any case, Pop Art obliterated that continuum decades ago.

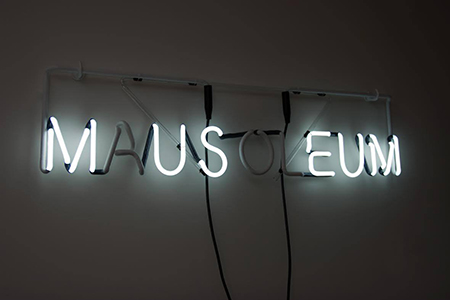

What happens, then, when a non-artistic phenomenon becomes reified as art? Certainly there’s something poignant in the specter of a dilapidated building in a decimated industrial center, but the minute a photographer with a Pratt MFA freeze-dries it with the click of a shutter and exhibits it as “ruins porn,” something essential about the referent has been perverted, perhaps even destroyed. Artists Scott Wayne Indiana and TJ Norris spoke to this in their 2007 neon sculpture, “M_US_EUM [postmortemism],” in which the letters “A,” “O” and “L” of the word “MAUSOLEUM” have been left unlit. Ergo, we infer, the very process of aestheticization inevitably renders the “MUSEUM” a crypt. And in the absence of hierarchy, we are left to look for fleeting glimpses of meaning and beauty, as did Oscar Wilde, in all the halls of the world: august, quotidian and every stratum in between.