For most artists, the human hand is an essential asset. As a tool for making art, the hand is almost always utilized, whether it be for applying paint, molding clay, working in Photoshop, or drawing on an iPad. Yet, when Bay Area artist Katherine Sherwood was just 44, an age when an artist is usually considered to be at mid-career, she lost the use of her dominant hand after suffering a stroke that left her paralyzed on the right side of her body. Displaying her resilience, the right-handed artist subsequently taught herself to paint with her left hand and shifted from working on the wall to working on the floor. This enabled her to reach her canvases more easily while moving around in a chair on wheels. In her recent exhibition at Walter Maciel Gallery, Sherwood addressed the negative stereotyping of people with disabilities, not only by serving as a positive role model, but also by exhibiting clever and compelling paintings that bring dignity and humanity to the subject of physical impairment.

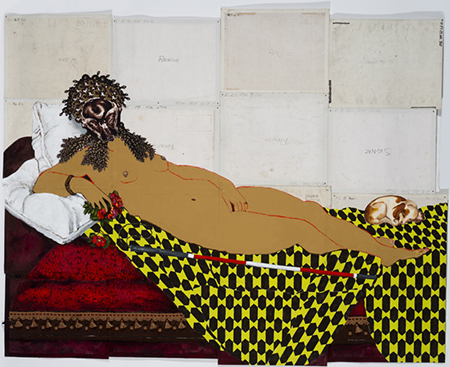

In one series entitled “Venuses,” Sherwood questions conventional interpretations of beauty, using art history as her point of departure. Instead of being painted on canvas, the “Venus” compositions are executed on the reverse sides of fabric art history reproductions that predate slides and digital formats as tools for teaching art history. In each, Sherwood appropriates a nude Odalisque from a well-known painting by such artists as Ingres, Goya and Manet, but substitutes her own brain scans for figures' heads and renders their bodies as either missing a limb, wearing a brace, or accompanied by a cane. Each woman is portrayed as a princess sporting an ornate crown or exotic headdress (also composed of brain scans) while reclining on a bed of vibrant geometric patterns. Metaphorically, these paintings provide an insightful counterargument to the current President's mockery of people with disabilities, suggesting that they can be as attractive, sexually desirable and happy as anyone without a disability.

Sherwood's exhibition also included a related series of still lifes, entitled “Brain Flowers,” that likewise are painted on the backs of art history illustrations. In compositions derived from paintings by Manet, Van Gogh, Matisse, and Cezanne, Sherwood replaced some of the flowers of each bouquet with new ones made from fragments of her brain scans, suggesting that our brains are as organic as flowers, and are but one of many organisms that make up a flourishing human body.

There are in fact a number of high profile artists who, at some point in their life suffered a significant disability, but were nevertheless determined to carry on. Chuck Close, for example, became paralyzed from the neck down as a result of a spinal artery collapse, and subsequently taught himself to paint with a brush strapped to his wrist while seated in a wheelchair. Op Art pioneer Julian Stanczak (1928-2017), who was right-handed, lost the use of his right arm and hand when he was a teenager, the result of beatings he suffered while imprisoned with his family in a Siberian Gulag. As Sherwood would do years later, Stanczak learned to paint with his left hand. He also invented a rotary device for cutting the masking tape used in painting his intricate abstractions. Similarly, San Antonio's Jesse Treviño, also right-handed, suffered severe damage to his right arm and hand after being injured from explosives and a sniper's bullet while serving in Vietnam. In order to learn to use his other hand to make art, he enrolled in college art classes and earned BA and MFA degrees. During the production of his 1997 mural "The Spirit of Healing," Treviño turned a so-called negative into a positive by using the hook of his prosthetic arm to cut most of the mural's 150,000 ceramic tiles.

An even more extreme disability was incurred by the Los Angeles painter Patrick Hogan (1947-1988), who at age five was diagnosed with Werding-Hoffman syndrome, a debilitating muscular disease that kept the artist wheelchair-bound from age ten. Known for rigorous abstract paintings made of acrylic and rope, Hogan reached a point where he could only paint by holding the brush with his mouth, and managed to do so successfully for a time near the end of his abbreviated life. Hogan's and the other artists' stories of triumphant perseverance suggest that there may be something inherent to creativity that enables us to overcome seemingly insurmountable obstacles.