Continuing through January 15, 2012

Born, raised, and trained as an artist in Los Angeles, Mark Bradford’s paintings seem an odd yet very precise reflection of French and documentary film influence. That his work bears, in part, the look of the mid-20th century affichistes (French for “poster makers”) Jacques Villeglé and Raymond Hains is less intentional than would be the connection to Chris Rock’s film “Good Hair” (2009), a documentary on the fake straight hair industry directed at African Americans. From the former can be discerned a perhaps unwitting precedent for Bradford’s inclusion of everyday paper stuffs – signs, advertisements, and hair salon accessories – into the large lacerated, woven and layered surfaces of his paintings. The hair salon accessories provide the link between Bradford’s painting and Rock’s film. More to the point is the spirit of a cultural bridge between high and low: the world of blue chip painting to the everyday goings-on of a women’s hair salon, in particular his mother’s in L.A., from which the artist stealthily absconds hair perm endpapers for use in his paintings.

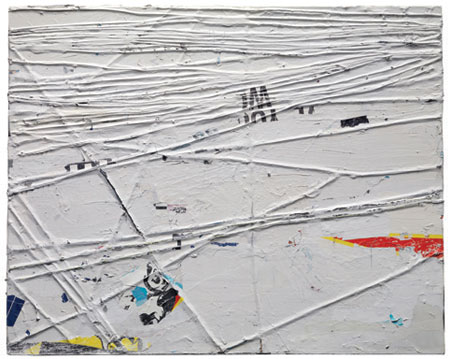

“Enter and Exit the New Negro” (2001) at 9’ x 8’ is mid-sized relative to most in the show, and is covered in onion skin-like rectangular hair perm endpapers. There is a field of white acrylic paint underneath, which is given an off-white, almost yellow patina by the endpapers. While largely an abstract painting, the endpapers introduce a subtle sense of everyday life. Like Villeglé and Hain’s posters torn from the walls along the streets of Paris, the hair perm endpapers inject an unnamable force of urbanism, namely the city life of his mother’s hair salon. At the same time they create a sense of gesture in a white field of paint along the lines, but with such different means, of Robert Ryman’s white paintings. In later works, such as “Scorched Earth” (2006) and “Mithra” (2008), the hair perm endpapers disappear and the works becomes wholly about engagement in the city. “Scorched Earth” is a cartographic interpretation of the Tulsa race riots of 1921. “Mithra” is a three-story hull of a wooden ark that Bradford originally installed in the Ninth Ward of New Orleans as part of the “Prospect.1” art festival there. The proverbial street – as a place for walking, ruminating, begging, sleeping, being beaten, and protesting – is vibrantly present in both of these pieces.

While Bradford’s work is extraordinary, collectively speaking a true feat for painting, the power of his work – its finesse, craft, and savvy combination of sophistication and kitsch – is slightly dampened in this incarnation. With the exception of “Mithra,” which is installed with frankness and aplomb, the work feels at times swallowed up in the vast precincts in which it is installed here. As a traveling show that originated under the auspices of Christopher Bedford at the Wexner Center for the Arts in Columbus, Ohio, we might fathom a slightly tweaked exhibition space, something perhaps more contemporary and intimate and less Roman and anonymous than the barrel vault at the DMA.