Opening January 22, 2012

The precepts and implications of architecture have long captivated New York-based painter, printmaker, installation artist and writer Peter Halley. His instantly recognizable abstractions concretize architectonic rigor; he runs his Chelsea studio with the precision and scrupulously delegated authority of an architecture firm; and after the initial sunburst of critical discourse surrounding the art movement he helped spur in the 1980s, neo-geometric conceptualism (aka “Neo-Geo”), he found that Neo-Geo’s central concerns were taken up by architects such as Rem Koolhaas, even as they were largely dropped by artists. This orientation toward architecture dovetails with a body of thought contending that public and private space — from the rise of agrarian culture to the vertical metropolis of the present day — have been geometricized for purposes of coercion. The seductive geometrics of technology may in fact be instruments of enslavement masquerading as liberation.

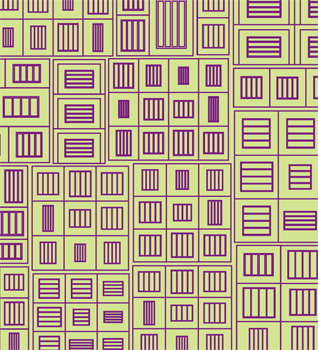

In his widely read essays, Halley applied Foucault’s essay "Discipline and Punish" and Baudrillard’s text, "Simulations" to his own theses and their visual expression: a devilishly iconoclastic vocabulary of squares, rectangles, and connective conduits, garishly colored and laden with the ceiling-popcorn material known as Roll-a-tex. Beginning in 1981, Halley painted prison bars inside the hitherto sacrosanct modernist square and rectangle so exalted by the likes of Piet Mondrian and Barnett Newman. These prisons (and other, barless squares and rectangles, which Halley dubbed “cells”) willfully literalized forms that modernism once held up as spiritual ideals.

It is this same barred, rectilinear motif that Halley deploys in the installation "Prison." The venue is apt. As one of Portland’s most sociable spaces, Disjecta lends itself to this exploration of space and the social. Wrapping around three long walls inside the soaring, barn-like exhibition hall, a smooth, seemingly seamless stretch of prison-patterned appliqué unfurls. With tongue not quite fully in cheek, the artist calls it “wallpaper.” Two adjacent walls, bare except for yellow DayGlo paint, are dappled with colored directional light, which lends acidic, post-nuclear atmospherics, in keeping with Halley’s Pop-influenced predilection for technological, rather than natural, light. Stacked one upon one another like an infinitude of tiger cages, the prisons exert a collective intimidation that verges on the sadistic.

After spending some time in the space, however, viewers may find their initial experience of confinement and dread yielding to feelings of expansion and amphetamenic rush, induced by the frenetic moiré effects of myriad repeated vertical and horizontal lines. The psychological and visceral experience continues to pivot between oppressiveness and exuberance in a whiplash of Charles Jencksian double-coding. On one hand, the prisons seem to metastasize as if on some sinister manifest destiny pulled from the pages of science fiction: the hive mind of "Star Trek’s" Borg, "The Matrix’s" vast network of fluid-filled pods, and the exponentially replicating monoliths of Arthur C. Clarke’s "2010: Odyssey Two."

Conversely, they emanate a wonky good cheer — perhaps even a downright cuddly-cute, stuffed-animal adorability — that flows from Halley’s particular strain of absurdist humor. Perhaps the prisons are more Tribbles than Borg. Either way, opening-night viewers who traversed the space, noshing brie, sipping bad Chardonnay, found themselves turned into players in the codified semiotic game of social and aesthetic intercourse. Whereas Halley’s acrylic paintings present discrete diagrams of contemporary experience, "Prison" expands into vaulting architectural space, rendering the exhibition hall itself a life-sized simulacrum indistinguishable from reality, with viewers the unwitting or complicit pawns in their own corralling. This adds up to an exhilarating, unsettling immersion.