Continuing through April 15, 2012

In 1971 on a Saturday morning I wandered into the Gladys K. Montgomery Gallery in the heart of the Pomona College campus. A young artist was quite busily enjoying himself creating an installation in the gallery. He had just begun with his work and was taping large flexible strips of wood in looping curves to the walls and floors of the gallery space using regular masking tape. The wood ranged from factory-fabricated strips of flexible white pine to sticks and tree limbs gleaned from nature. The work was certainly “environmental” in its use of gallery space, but it was also insouciantly impermanent and defiantly transient. There was also a good deal of humorous reflexivity in its placement within a prestigious gallery. The artist was John M. White.

After determining that I was genuinely curious, White asked for my opinion about the nascent work. I applauded its impertinence and the artist gave a sly smile. It was evident to me that I was in the presence of a first rank aesthetic trickster, an artist whose abiding passion was an inquiry into the processes of art-making itself. And that has indeed proven to be the case.

Since the early 1970s, White has engaged in a multi-media attack upon fine art that embraces performance art and installation as well as drawing and painting. The current exhibit focuses on two recent series of paintings and drawings.

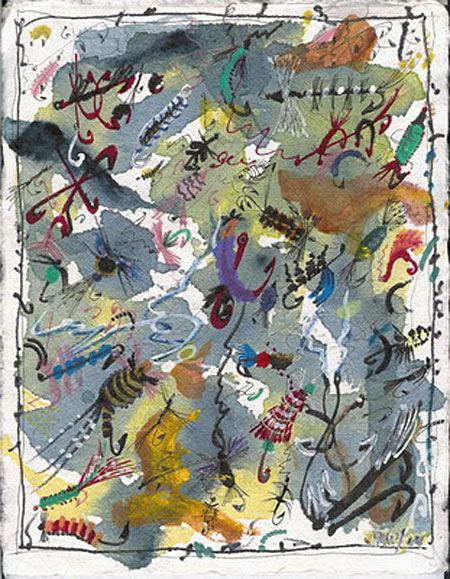

White’s “Artificial Hatch” paintings are playfully gestural and colorfully abstract. The artist is a devout angler, and these paintings are his attempt to convey “the joy and excitement fish must feel in the presence of a fresh insect hatch.” That’s one way to approach the work. With their notational playfulness White creates a language based upon a floating world in which symbols, objects and light collide.

These are works made on paper that possess the immediacy of Japanese calligraphy. Once the pigments and paints hit the paper, they remain what they are. A performative energy, the balance between accident and a studied gracefulness, informs them. This playfulness of the inscribed “accident” makes the work daring and immediate. It nevertheless remains a kind of childlike and alien visual language that is distinctly in White's voice, while also recalling the exploratory abstraction of Joan Miro and Paul Klee.

The black and white “Mind Field” drawings are as much like writing, or a kind of idiosyncratic doodling, as image making. These drawings were initially undertaken as a memorial to a boxer who perished from injuries sustained in the ring. They depict highly biomorphic forms floating on a planar space that are increasingly frenetic as the series progresses. It’s noteworthy that White keeps finding his way back to a childlike approach to making art that is highly personal, with a continuous insistence upon individual expression that is light yet aesthetically serious. That may be, perhaps, account at least in part for White’s enduring appeal and a part of his strategy for continuous self-reinvention.

By reiterating the importance of playfulness in art White has kept the ethos of the trickster alive. This ethos was embodied in the 20th century by Marcel Duchamp, whose aesthetic milieus also reached beyond that of painting into film, performance and conceptualism. White is a 21st century trickster whose art is equally various.