February 26 - May 26, 2012

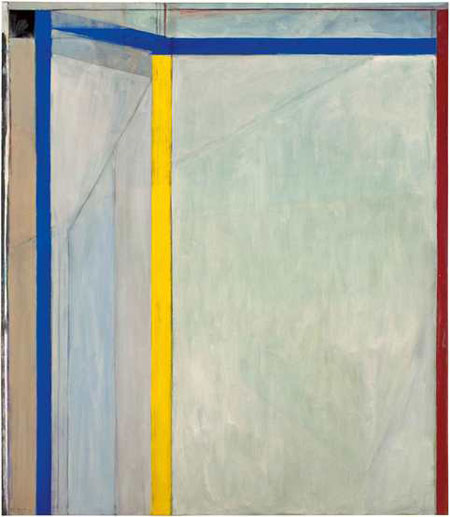

Many regular visitors to OCMA have long been enamored with this venue’s "Ocean Park #36" (1970) by Richard Diebenkorn, acquired some 35 years ago and currently ensconced in this latest contribution to Pacific Standard Time. Distinguished by its sharp blue and yellow lines and luminous interior space, the work relates to the nearby sea and sky. "The Ocean Park Series" is also a homecoming of sorts, as Diebenkorn was friendly with Newport Harbor Art Museum’s (OCMA’s prior name) former chief curator Paul Schimmel. It encompasses 20 large paintings, 18 small and medium prints, 30 small drawings and collages, and 12 very small paintings, including pieces on cigar box lids. While dense, the show is also spacious, allowing visitors to study the smaller pieces; as well as the lines, dimensions and varying layers of the larger pieces.

A comprehensive timeline accompanying the exhibition chronicles an artist who pursued his lifelong passion through drawing, painting, dialogues with fellow artists and inveterate museum visiting. A seminal moment occurred in 1943, while on active Marine duty. Diebenkorn was assigned to Quantico, Virginia, from which post he visited museums all over the East Coast, often attending Washington, D.C.’s Phillips Collection, spending long hours looking at works by Henri Matisse, whose approach to painting influenced the aspiring artist. In “The Art of Richard Diebenkorn” © 1997, the artist is quoted in 1974 about seeing a Phillips-owned Matisse that inspired many of his later compositions. He said about the Matisse, “I noticed its spatial amplitude; one saw a marvelous hollow or room yet the surface is right there … right up front.” The Phillips Collection, itself the owner of "Ocean Park #38" (1971) from the current show, includes in its didactics that this Diebenkorn work, “is characterized by broadly brushed surfaces of luminescent and atmospheric color, specifically that of bright yellows … [he] activates the corners of the work and unifies the canvas through varied linear elements — both horizontal and diagonal — to ensure the viewer will examine the entire surface.”

In 1966, Diebenkorn moved to Santa Monica’s Ocean Park area. Living in this light-filled environment inspired him to devote the rest of his life to abstraction. He explained, “The abstract paintings permit an allover light which wasn’t possible for me in the representational works, which seem somehow dingy by comparison.” He began creating each "Ocean Park" painting first by sketching directly onto the canvas, following that with paint, working laboriously while continually refining the work. Curator Sarah Bancroft writes in the accompanying catalog, “The artist worked and reworked the canvases … building up not only layers but an array of abstract geometric relationships and lines as well, atmospheric fields and planes.”

As with many abstract works, viewers often try to explain what the artist is representing. Some people say that "Ocean Park" pieces depict Diebenkorn’s studio window view, others, the luminous Southern California light. Still others describe the works as being influenced by the aerial landscape. The artist himself said in 1987, “I was first struck by the aerial views when I was flying back to California from Albuquerque … I guess it was the combination of desert and agriculture that really turned me on, because it has so many things I wanted in my paintings. ”

Indeed the paintings rely on a variety of southwestern colors, including blues and greens, tans, warm grays and yellows. Diebenkorn’s use of color, set into a broad and luminous painterly field, is often cited as reflective of his Ocean Park neighborhood. Peter Levitt, who lived there as well, explains in the catalog, “… the paintings call forth how it actually felt to live bathed in a wash of such color and light, to feel the steady, calm and gradual movement of time reflected in the environment as one lived one’s moments, days, months and years in a small seaside town …” Yet toward the end of the artist’s life, and influenced by his mother’s death, he gravitated to browns and blacks. Among these darker works is "Ocean Park #138" (1985) with its broad swath of black paint.

Early works from 1968 also tend toward darker colors and imply elements of figuration. In "#6," vertical organic forms that mimic the female body dominate, while smudges across the center suggest activity. The fields of luminous blue in "#16" are applied in many thin layers in counterpoint with thick red, yellow and orange lines. OCMA's "#36," with its broad plane of misty blue paint, has architectural features and lines that mirror Matisse. One of the few horizontal pieces, "#68" (1974) is dominated by greens, applied in layers, with stripes of blue and black that feel like a broad green lawn seen from a porch. There is greater opacity in "#79," "#83" and "#87," all from 1975, along with well defined vertical and horizontal planes.

The smaller works, including the cigar box lids, echo the compositions and colors of the major paintings, but their surface is rougher and more textural; many are on wood with more diverse mediums, including watercolor and graphite. Several of these smaller pieces, however, provide contrast; three "Untitled" pieces (1980-81), on paper with varying media, have shapes and patterns that quote the biomorphic works of Miro and other early modernists.

In a recent interview, I asked Sarah Bancroft how she feels seeing so many "Ocean Park" paintings gathered together. Her answer: ”Exquisite bliss and calm … Each one is captivating, but together, they start singing and having visual conversations, and it feels like being embraced by a beautiful choir full of abstract altar pieces. When you're working in the galleries, you feel that the work is communicating directly to you. During the installation, it's just the crew, me and the artwork and I'm meditating on the placement and flow of the exhibition and it is very joyous and Zen. The paintings set the tone."

Published courtesy of ArtSceneCal ©2012