Given his importance in defining the West Coast art scene over the past six decades, there is a strong temptation to claim Peter Selz as a West Coast figure, to proclaim him as a "pioneering West Coast curator and art historian." In fact, while he was--and is--all that, as this engaging biography by Paul J. Karlstrom makes clear, Selz's remarkable career played out on a national and international stage. Born in Munich in 1919, to a German Jewish family, in what was to be the Bavarian heart of Hitler's Germany, Selz fled to the US ahead of the storm while a teenager. From his first experiences with the 57th Street galleries in New York, he joined the army and emerged at the University of Chicago, where he did his dissertation on German Expressionism. By the time Selz arrived in sleepy Pomona, California in 1955, on the outskirts of Los Angeles, his was already a finely-honed intellect with a deep appreciation for European art history. From Pomona, where Selz helped identify the movement known as Abstract Classicism, or hard-edge painting, Selz was plucked to be the curator of modern painting and sculpture at the high temple itself, New York's Museum of Modern Art. During his tenure, he curated "New Images of Man, as well as significant monographic exhibitions on Rothko, Dubuffet, Beckmann and Giacometti. In 1965, Selz returned West, this time to Berkeley, as director of the University Art Museum. Berkeley in the Sixties had become a hub of political activism, and (literally) a hotbed of sexual and social experimentation, and both spheres apparently appealed to Selz.

Karlstrom's book delves freely into the public and private aspects of Selz's life and the behind-the-scenes struggles that marked both, giving testimony to the zeitgeist Selz inhabited and his own, cultural joie de vivre. It is, intentionally, a warts-and-all biography; Karlstrom, a devoted interviewer and former West Coast director of the Smithsonian's Archives of American Art, quotes not just Selz, his friends, and family, but also those who disagreed with him along the turbulent trajectory of his public career and personal life. The result is not so much an artistic hagiography, but more of an affectionate, Rashamon-type deconstruction of long-past events, jumping back and forth in time and POV, at times rather dizzyingly. As such, it is a highly engaging journey. Despite the many artists Selz knew and worked with, from Rothko and de Kooning in New York, to such iconoclastic figures as Bruce Conner, Hans Burkhardt, and Nathan Oliveira on the West Coast, Selz fully occupies the heart of the narrative and remains a complex and compelling protagonist. The book's subtitle, "Sketches of a Life in Art," defines its vision best: the volume is not just about the art per se, but about the lives of those who made it, promoted it, defined it, debated it, and at times, fought over it. But who also loved it, lived it and breathed it. Today, at 93, Selz remains active as a curator and historian; a new show he curated called "The Painted Word," on visual art by San Francisco Beat-era poets and writers of the '50s and '60s, runs through June 9, at the Meridian Gallery. (By way of happy disclosure, he is also a regular contributor to art ltd.). This excerpt discusses Selz's return to California from New York, and his seminal exhibitions, "Kinetic Art" and "Funk," in 1967, during his first heady years at Berkeley.

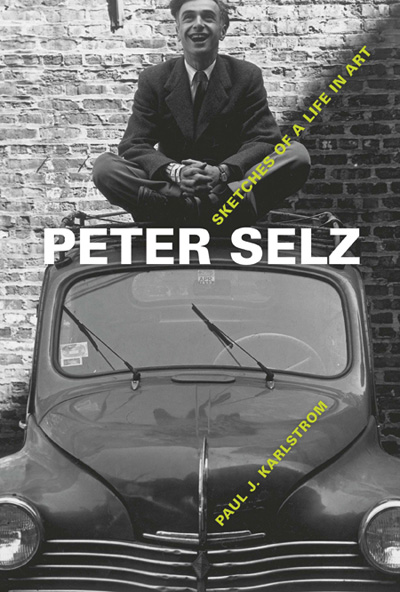

- George Melrod

The move from New York to "laid-back" California put Peter in touch with a counterculture that seemed organic and natural to the place rather than invented or imposed. It provided the context for him to realize the full liberation he had sought earlier and that in a fundamental way represented his authentic personal identity. Aligning himself with artists and their natural readiness to step outside the rules of art and society, Selz still likes to think of himself as a sympathetic mediator between artists and the essential institutions-- museums, universities--that serve them, or should do so. Each of his books and exhibitions was based on the idea that the creative individual, the artist, was at the center of the whole cultural enterprise, not the scholar or the curator. Peter places himself in the artists' camp.

Selz's exhibition record at Berkeley, whether at the old Powerhouse or in the new Ciampi building, is an impressive one. The kinetic art show, the first with Selz as director, remains the one he generally points to as his most historically significant. "Directions in Kinetic Sculpture" grew out of Selz's encounter with the work of Jean Tinguely and most immediately the 1960 installation at MoMA. Selz was fascinated by the introduction of motion and change into art making, with the subject of the sculpture becoming movement itself. And he saw the issues and ideas involved, especially time and change, as fundamental to modernist thinking...

"Directions in Kinetic Sculpture" featured the work of fourteen sculptors, only four of whom were American, and boasted several "firsts": it was not only Peter's first show at Berkeley but also the first show of kinetic sculpture in the United States; it featured the first catalogue essay by kinetic sculptor George Rickey; and it introduced a struggling young San Francisco sculptor, Fletcher Benton, whose career took off thanks to his inclusion in the exhibition. Benton was eager to go on record recalling his fortuitous "discovery" by Selz, at the same time expressing admiration for what Peter contributed in a broader sense to Bay Area art and cultural life:

"The word got out that this Museum of Modern Art curator had taken a professorship at Berkeley. And he totally changed, from my point of view, the local atmosphere and the hopes of the artists... So we all felt that this man was a god--that he was going to do great things for the Bay Area... One day I got a phone call: 'This is Peter Selz.' And anybody who's talked to Peter knows he has this deep, impressive baritone voice. He had heard that I was making some moving things, wall pieces. And he asked if he could come by to see them... Well, in a few days he showed up, and he was so friendly... He looked at what I had and asked me if I would be interested in being in the show. I had no idea what he was talking about. I didn't even know there was a [kinetic art] movement... And then... Time magazine did an article [on the show]... and my phone started ringing off the hook. I was in many other kinetic shows, but never such a pioneering group as the one Peter brought here."

In a similar way, the "Funk" show helped define Selz's career at UAM, and was certainly at least as important for the local scene. But exactly what was Funk? How was it identified as a distinct phenomenon, and how were the artists selected? Selz found this important question difficult to answer. "Well, I don't know. In the catalogue to the show I wrote that Funk can't really be defined. When you see it, you know it. But it was a kind of art which was totally irreverent, an art that was loud--I said "unashamed"--in a way that relates to Dada and was very different from the Pop Art... A casual, irreverent... art, art which dealt with bodily functions... biomorphic art which was sloppy rather than formal."

Selz thinks of Jeremy Anderson as "sort of the daddy" of Funk, but looking back, he singled out Wiley and Arneson as the leading exponents. He goes on to say, "There were dozens of people in Berkeley, Davis, San Francisco, and up in Marin County who were doing this kind of work." Along with his staff--assistant director Tom Freudenheim and curators Brenda Richardson and Susan Rannells--Selz went to "a great many studios," and together they picked 27 artists who they felt represented the "movement." Selz would not use the term movement today for funk, even though his exhibition implied some cohesiveness. The artists surely did not feel they were part of a movement; in fact, they resisted the idea. Selz now, if not then, is very much aware of the limitations of the term in regard to individual artists and works.

"With all its color and... irreverence," Selz recalled, "it seemed like a marvelous show, [which] put its finger on a certain pulse of this land of funk... this bohemian kind of art." It had a somewhat mixed response, however. The public "loved it, almost as much as they loved the kinetic show. They thought it was a delight... That was a popular response. The art critical response was slightly different: Artforum tore it to pieces. Artforum [founded in San Francisco, then moved to Los Angeles] had moved from California to New York and was taken over by the Greenberg contingent, so they hated it. But in general the response was very, very positive."

From the moment of his arrival in Berkeley, Selz had been interested in the "totally different... local kind of thing" he observed in the art being made in Northern California. He and his museum colleagues, as well as some of the artists themselves, soon began talking about the idea that became the "Funk" show. And Peter says it was at his suggestion that his best artist friend and UC Berkeley colleague, Harold Paris, had published an essay on the subject in Art in America a month before the show opened. Selz was attuned to what was original in reflecting a peculiarly Californian sensibility, and the selection of artists presents a similar attitude and aesthetic: much of the work looks the same. Among the artists, Selz particularly admired one: Bruce Conner. In his opinion, in fact, Conner was possibly the most important artist working in California, from the standpoint of pure creative originality and power of statement...

Several of the artists in the "Funk" show received this preferential attention, but none more than Bruce Conner. Even Harold Paris and Pete Voulkos did not seem to ignite Selz's passion to the same degree. But in a phone conversation a year before he died in July 2008, Conner was unexpectedly withholding--one might even say ungrateful--in his comments... His main complaint in general, but in this case clearly directed at Peter, was that the support he'd received had little influence on sales. He further claimed that he'd had no income for the past five years. Peter was understandably disappointed by this criticism, but he also understood that Bruce was in a sense a perpetual outsider, challenging the art establishment and especially the market, despite his being represented by devoted dealers such as San Francisco's Paule Anglim... [But] Selz's opinion of Conner's importance remains unchanged... "More than the other artists, many of whose work did not go much deeper than a blase surface irreverence, Conner was profoundly engaging the major issues of the human condition."...

Wally Hedrick provides insight into one of the controversial aspects of the Funk art exhibition. Many of the artists, despite the recognition that the invented catch-all term conferred, objected to it, Hedrick chief among them: "Yeah, I think Selz was just trying to give us a working term... And he has given the artists a style. [But] the artist's job is to do the work. The museum person should be accurate and check his facts, try to get them straight... And this is what I guess maddened the people I talked to, it [the show and term] gets international recognition, and it's all based on an inaccuracy. Here's a reputable guy who is now known internationally for something that's a fraud. I personally don't care, but a lot of people are upset about it."

Harold Paris provided a much less angry response and a more evocatively descriptive view of the phenomenon in his "Sweet Land of Funk" article for Art in America:

"The artist here [San Francisco Bay Area] is aware that no one really sees his work, and no one really supports his work. So, in effect, he says 'Funk.' But also he is free. There is less pressure to 'make it.' The casual, irreverent, insincere California atmosphere, with its absurd elements--weather, clothes, 'skinny-dipping,' hobby craft, sun-drenched mentality, Doggie Diner, perfumed toilet tissue, do-it-yourself--all this drives the artist's vision inward. This is the Land of Funk... Idiosyncratic, eccentric, its doctrine amoral... In essence 'a groove to stick your finger down your throat and see what comes up.'"

In its rhythmical cadence and random listing of arbitrary characteristics, this description reads very much like a Beat-era poem. Indeed, the attitudinal connections between these artists and poets and jazz musicians characterized the creative community of the Bay Area, where there was, above all, the intersection of art and politics. This is what Peter was looking for and found in California.

Curator Connie Lewallen, describing the unusual situation at Berkeley in the 1960s, outlines the cultural framework that not only distinguished Selz's new environment but also pointed in the direction the new museum was to take. Berkeley, more than any other location, brought the antiestablishment forces at work in America together in a university-based protest counterculture that is generally regarded as without precedent in this country. The major social and political issues of the day took hold in and around the Berkeley campus, providing a focal point for debate and action, a kind of mirror to contemporary American social change. The broader context, Lewallen points out, was the Vietnam War, which "defined the consciousness of the late 1960s and 1970s... The fulcrum of protest against inequality at home and the war abroad was the University of California, the scene not only of countless antiwar demonstrations but also of the Free Speech Movement, the 1969 third-world student organization strike, which met with violent police action, and conflicts over People's Park."

Within this volatile atmosphere, the University Art Museum demonstrated, from its earliest years, a commitment to radical, politically engaged new art. It was in Peter Selz's nature to pick up the activist cause immediately upon arrival (in fact, he claims that confrontational politics were part of his attraction to the Berkeley job), and he did so looking to the Bay Area assemblage movement on which the "Funk" show was based. Lewallen called it Selz's "eponymous 1967 exhibition," pointing to the characteristic use of found objects and urban debris that was suggestive of decay. Sexual and political overtones characterized the work of the Beat-era literary and art underground, which provided the foundation for the decade's cultural "upheavals" and the emergence of a new avant garde. Lewallen's claim that the art museum was one of the major sites to recognize and bring to public view radical changes in the visual arts does not seem overstated.

In a surprising contradiction, however, Selz says that making such sweeping claims for Funk as a series of illustrations of the times is overreaching... In the case of the "Funk" show and the admittedly varied works on display, he insists that he and his colleagues... had no large goals in mind. They were interested simply in recognizing what they saw as a regional manifestation of the larger assemblage movement... "We did not think this was an Important Art Movement, but we saw it largely as a fun thing to do in keeping with the work itself... ." Despite this disclaimer regarding art-historical intentions, Selz now describes Bay Area Funk as the last significant regional movement in America...

Art historian Sophie Dannenmuller takes a slightly different point of view in terms of Funk as an art phenomenon with a particular relationship to assemblage. She sees Funk art and California assemblage as two distinct movements, converging in the work of certain artists at specific times. For her, Funk is above all a uniquely Bay Area expression of an aesthetic attitude, one that encompasses assemblage but is not restricted to a single medium (as was assemblage). Politics may be present, but it remains peripheral to the "movement's" core identity, which is a "countercultural and anticonformist [not just non conformist] aesthetic attitude."

The importance of Selz's "Funk" exhibition, according to Dannenmuller, was that it introduced the art world to that specifically Northern Californian aesthetic. (Even France learned of it, through a 1970 article in the magazine L'OEil by art critic Jose Pierre.) It may be that the "Funk" show, with its sly irreverence, playful humor, and sociopolitical commentary, was closest to Peter's own sensibilities, even though the preceding kinetic exhibition was internationally more significant. Funk represented the bohemian ideal of unfettered creative freedom. In its sexual forms and imagery, it reflected aspects of the libertine lifestyle that so attracted Peter and in which, through his friendship with artists, notably Harold Paris, he became an enthusiastic participant. In California, Peter learned that one could do more than just make a living in art; one could actually live art.

This article was written for and published in art ltd. magazine ![]()