Continuing through September 8, 2012

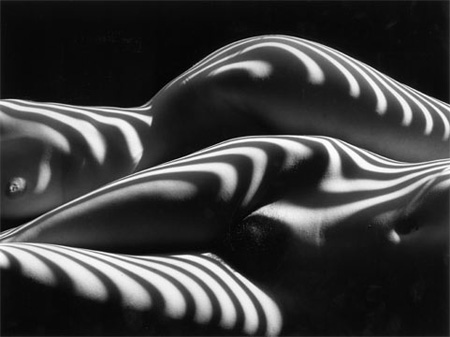

In this selection of photographs by Lucien Clergue we are witnesses to the re-birth and transformation of ordinary things. Undulating sand dunes become nudes in a re-vision that pulls together lines and forms into an erotic illusion. Waves and boulders unite and become wombs. Animal and human worlds merge into zebras. Drawn from more than a half-century of work, Clergue’s powerful but simple vision compels the viewer to experience images shaped by a lifetime of exploring the possibilities of the camera.

A native of Arles (born in 1934) he was a son of divorced parents who lost everything in the Allied bombings of World War II. His mother recognized the artist in the child, and at the age of thirteen bought him a cheap camera. She died when he was eighteen, he left school and began working in a factory. But even under these circumstances he dreamt of making films like those of his idols, the Italian social realist directors. Encouraged by the writer, Jean-Marie Magnan, a fellow Arlésien, he acquired a Semi-Flex 6x6 and began taking photos of Arles and its ruins, its Roman necropolis and its crumbling buildings. Creating tableaux vivants of children dressed as harlequins, he conjured the past, the comic and tragic life of thecommedia. These static and theatrical visions are a dichotomy: movement captured by the photographic still.

His passion was and remains Arles. In 1952, in its Roman amphitheater he met a guide, a painter who would become a friend, a critic, a mentor and a subject: Pablo Picasso. Through his presence, his world expanded. He encountered and made friends within Picasso’s circle: Jean Cocteau, with whom he would collaborate, and Max Ernst, his first collector. In 1956, he began photographing nudes on the beaches of the camargue. These would appear in his first book, "Corps Mémorable" with poems by Paul Eluard and an introductory poem by Cocteau.

The year before, on impulse, he joined the gypsies who had come to Arles on a pilgrimage. Through them, he asserts, he found the sun. He met and became friends of José Reyes, the father of the Gypsy Kings, and of Manitas de Plata, the Flamenco guitarist. He would forge a life-long bond with the gypsies, taking photos of their dances, their music making and of the bullfight.

These painters, poets, musicians, writers all shared similar thoughts, feelings and ideas. Not simply biographical footnotes, these friendships, these encounters become the tools that formed and continue to inform Clergue’s masterly eye. There would be more: Ansel Adams, Edward Steichen, Saint-John Perse, Robert Rauschenberg, David Hockney, among others. He would travel the world and receive countless accolades and honors. But he remains faithful to the history of the camera and of film. These interrelationships with the creators of modernity challenge Clergue to probe beyond the visual object, uncovering the line and flow, the composition that constructs the image.

In “Langage des Sables (Language of the Sands), Camargue" (1976) the ebb and flow of the tide on the sand, the tracks and traces of seaweed recede into an abstraction of lines and patterns that emerge from the rock formations along a shore. The suite from which this is drawn was accepted as his doctoral dissertation at the University of Marseilles-Provence upon the recommendation of the philosopher, Roland Barthes. Photographs of sand, mud salt water and sun were created on the beaches of the Camargue, Point Lobos and White Sands, New Mexico.

“Nu Zebre, New York" (2005) is a composition of waves of black and white stripes. A single eye peers out from within the folds. What we see is the stark simplicity of curvilinear forms. This union of zebra stripes and a nude is a haunting reminder of the relationship between human beings and the animal kingdom. Are we them and are they us in this cosmological configuration?

In "Two Nudes" we are again torn between thought and feeling. What we see is an undulating landscape. What is there are nudes. We waver between what we rationally think we see and what is truly there. What we feel is the pulsating rhythm of the lines and curves before us.

Referring to “Langage des Sables, Clergue" Barthes wrote “… through the culture of Trace, Clergue touches upon two distinct levels of photography. The first is painting. The second is magic, which is essentially an inspired reading of Traces.” Barthes goes on to assert that “… for pagan man, nature is nothing but that surface of the Earth that has been marked by the track of the Gods.” Barthes is not alone in defining these photographs as works of magic. Under their spell, we discover new views, and I reiterate: we become witnesses to the re-birth and transformation of ordinary things.

Published courtesy of ArtSceneCal ©2012