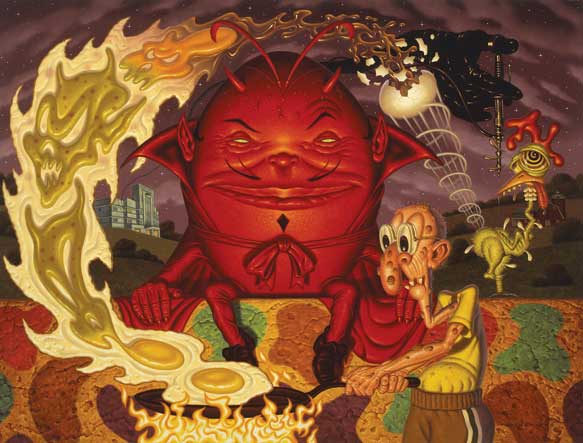

The Deviled Egg 2000 Todd Schorr Acrylic on canvas 30 x 40 inches

Collection of Elizabeth Wang-Lee and Oliver Hengst

Photo: courtesy of the artist and The San Jose Museum of Art

The vast landscape of the lowbrow art world can potentially be put into a number of pluralistic categories: Pop Surrealism, the emotive, highly stylized illustrative community, graffiti (in its most pure form) and its urban/street subcultures, punk art, surf and skate indulgences, and those from the comic world. As all of these categories have seen an increase in popularity—and a good deal of critical acclaim—in recent years, the discussion about lowbrow’s validity has progressed to an interesting point. Within the last five years or so, a number of regional museums have begun to recognize the abilities of the leaders of the lowbrow movement by giving their work careful consideration within a traditional museum setting. It has been nearly 50 years since the contemporary lowbrow scene’s inception, through comic and hot rod artists planting their anti-art-establishment roots. Now we are gaining the opportunity to gauge the progress and sophistication of the first few generations of that movement on a more level playing field.

A couple of group exhibitions and individual efforts are notable for breaking the elitist barrier into these venues. “Beautiful Losers,” curated by Aaron Rose and Christian Strike, examined the subcultural and visual phenomenon of skateboarding, punk, hip-hop, and graffiti. The exhibition opened at the Cincinnati Contemporary Arts Center in 2004 and focused both on the roots and influential leaders of these movements, including Raymond Pettibon and Jean-Michel Basquiat. The exhibition has since traveled to four continents including multiple regional museums nationwide in the United States.

In 2008, the Laguna Art Museum hosted “In the Land of Retinal Delights: The Juxtapoz Factor,” a retrospective with a similar structure to that of the “Beautiful Losers” project. Assembled by Meg Linton, an independent curator who holds other positions at the Otis College of Art and Design in Southern California, this exhibition focused more on the illustrative and Pop Surrealist factions of the lowbrow movement. Robert Williams founded Juxtapoz Magazine in 1994, and has had an undeniable influence on the Southern California art scene in particular. Both the Laguna Art Museum and the San Jose Museum of Art have been major proponents of elevating the status of lowbrow artists, as well as validating the significance, relevance and sophistication of their work. While it may take some time to reach the galleries of major museums in traditional United States art centers, the first museum doors have been broken down, and those responsible plan to stick around a while.

2007 saw the San Jose Museum of Art host one of its most popular exhibitions, in Los Angeles- based painter Camille Rose Garcia’s “Tragic Kingdom,” which served as Garcia’s first solo museum show outside the Los Angeles area. Now, in late June 2009 the SJMA will unveil “American Surreal,” an extensive mid-career retrospective for one of the most influential leaders of the Pop Surrealism movement, Todd Schorr. This extensive catalogue of work will feature mainly works from 2003-2008, including some of Schorr’s finest pieces such as The Amphibian Frontier (60" x 36", acrylic on canvas, 2008) and the astoundingly detailed Ape Worship (96" x 120", acrylic on canvas, 2008).

Schorr, 55, hails from the East Coast and graduated from the Philadelphia College of Art (now the University of The Arts) in 1976. In 1998, he relocated to Los Angeles to work in the place where a great amount of his critical acclaim and patronage is centered. His desire to be a fine art painter was redirected to the illustration department, which would serve as technical backbone for his work. Influenced greatly by the godfather of lowbrow, Robert Williams, Schorr’s complex formal strategies combine elements of American pop culture from his childhood and beyond with stunning illustrative realism. These lucid dreams manifest themselves in compositions evocative of many of the great masters like Pieter Bruegel and Hieronymus Bosch, while incorporating themes from Dali, Magritte, and de Chirico. Schorr’s work displays a preference for using marginalized outcasts of California pop culture to substitute for both primary and background subjects: carnival sideshows, pulp illustration and comics, classic cartoons, vintage science fiction, post WWII-era advertising iconographies and television, and the seedier sides of celebrity fantasy are all frequently at his disposal and employed throughout his work. Schorr combines these elements seamlessly together as if part of one very long, feverish dream in which seemingly impossibly juxtapositions interact as part of an otherworldly landscape.

One of the finer pieces of this retrospective is 2003’s The Parade of the Damned (60" x 84", acrylic on canvas) in which the artist provides his own contemporary take on Bruegel’s Dulle Griet (Mad Meg), from 1562, based on a Flemish folk tale. Bruegel was known for his emphasis on the vulgar, grotesque and absurd, which he combined with observations of human weakness and folly. Schorr’s finest works are those inspired by classics: his teeming panoramas seem to toy effortlessly with nearly impossible depths of field and are heavily steeped in satire.

Mad Meg is said to be acting out an old Flemish proverb: “She could plunder in front of hell and remain unscathed.” Meg is surrounded by an encroaching Armageddon, charging towards the gate of hell carrying a sword and a basket of pots and pans. In the background, people are mutating into unearthly creatures and the earth is scorched. The army is cowering and on the verge of defeat by Meg’s army of women; a ghastly mouth of hell, with the damned flowing in a river of blood and hideous people turned into half barrels or various animals. Schorr’s version substitutes a vintage Frankenstein character for Meg, flanked and followed by various other iconic entities from the realm of early 20th century film and fantasy. The mutant creature holding the boat with two men on its shoulders standing on a house next to the grain bin is, instead, a classic King Kong figure, holding a ’50s sci-fi spaceship with three extra-terrestrial passengers over his head.

While there is no direct connection between the chosen subjects in the respective works, both artists are cited as chroniclers of their own popular cultures. Bruegel was a painter who was cited as successfully combining the popular culture of his time with high art. Schorr should certainly be seen the same way. Both were able to direct a certain level of folk humor toward their respective targets; with Bruegel, the church and state, and with Schorr, the high art world.

The Corruption of Mankind Jeff Soto 2008 Acrylic on wood panel 144 x 60 inches

December 2008 saw the opening of the Riverside Art Museum’s solo exhibition of their favorite native son, Jeff Soto. Soto is a longtime resident of the inland empire, an area roughly 50 miles east of Los Angeles. In Soto’s work, representations of the area’s politics, economic factors, oil mining infrastructure, and natural vegetation are juxtaposed with dreams of science fiction and toy robots, and translated in a manner derived from skateboarding, hip hop, and graffiti culture. Entitled “Turning in Circles,” the exhibition served as Soto’s coming out party; at the age of 33, he has already influenced countless other artists of his scene and generation, throughout various circles. Soto’s earlier work has fallen victim to imitation, particularly those centering more on environmentalist themes or featuring robots, iconic cacti, and tentacles. Soto does have some roots in the Los Angeles graffiti scene, circa late ’80s early ’90s, before it became influenced so heavily by corporate graphics and incesticized with ad campaigns and product lines. But to my knowledge, you won’t be finding any shoes or fragrance bottles bearing Soto’s name.

Rob and Christian Clayton, both alumni of Pasadena’s Art Center, and fellow museum exhibitors, also taught at Art Center, where Soto was a pupil. From early on, Soto had stated a desire to master photorealistic painting; the Claytons and some of his other instructors influenced him to adopt a more traditionally painterly approach, wherein one’s inaccuracies can be seen within a piece along with successful risks taken, in order to more fully reveal the artist’s thought and technical process. The Riverside Art Museum exhibition highlighted a significant evolutionary period in the artist’s young career. Soto’s older work, from earlier in the decade, saw the construction of highly stylized characters that mostly existed in a world of warmer palette. These works often conveyed allegorical allusions to a range of issues, from the struggles by the human race to control the forces of nature for its own benefit, to man’s dependency on technology, and the physiological fusion of man, animal, and machine. Soto’s techniques over the years have varied, incorporating stencil, collage, spray paint, markers and drawings. To create the backgrounds of his paintings, Soto often uses images that are geographically familiar to him, such as cactus, desert flowers, telephone wires and the rolling hills of the high desert. These landscapes provide a backdrop for comic-like vignettes of interactions of man, machine and colorful anthropomorphic creatures.

Starting in 2008, we’ve seen a sophisticated intensity develop in his more recent darker work. Through his extraordinary technical skills and compositional formulas, Soto has clearly begun to distinguish himself from the rest of the pack of artists, boasting both an illustrative and graffiti background. Compare, for example, the progression between 2005’s Crying is Alright (111" x 21", acrylic on wood) and 2008’s The Corruption Of Mankind (144" x 60", acrylic on wood panel). Gone are the warmer, sunnier desert influences contributing to the flat, more cartoon-like work; in the newer work, a more radical symbolic language has become prevalent. Much of this body of work can be seen as representing a microcosm for many parts of the country during the current economic crisis, as Soto alludes to many regional issues, such as the suburban decay that has begun to set in to some parts of Southern California and the extensive job loss that has had a crippling effect on the citizens of Riverside and San Bernardino Counties. From a more formal standpoint, the recent emphasis on positive and negative space has become one of the strongest tools in Soto’s arsenal, heightening the tension within the work. Whereas older installations would flow continually into one another, the viewer is now forced to manage this condensed, capsulized imagery. For all these reasons, the Riverside Art Museum exhibition, which opened in December 2008 and ran through mid-February, marks the pinnacle thus far of Soto’s young career.

The partnership between these smaller-market museums and these outcasts of traditional highbrow institutions is particularly significant as we see other small American cities emerge as stronger art markets, and establish their significance in the face of the big three: New York, Chicago and Los Angeles. Look for the first major museum show for the Clayton Brothers at the Madison Museum of Contemporary Art in Madison, Wisconsin. For those planning on a trip to the Bay Area in the next few months, Todd Schorr’s “American Surreal” will run through September 16, 2009 at SJMA.

The lowbrow genre has never been considered to be on the same level as “high art,” especially with the latter having such close ties to traditional academic institutions and being more dependent on theory, which is less of an emphasis for the lowbrow community. However, in spite of resistance from various parts of the art world, lowbrow artists like Mark Ryden and Camille Rose Garcia have gone on to enjoy enormous financial success, and a great deal of critical acclaim, even before they’ve achieved regional museum exhibitions. The ascendance of their work in the marketplace, like these recent museum exhibitions, only strengthens the argument that these artists’ work deserve substantial attention, by all tiers of the art community.

This article was written for and published in art ltd. magazine ![]()