Continuing through August 19, 2012

A Berlin Dadaist is invited to Dallas by a department store executive … Sounds like a set up for a joke, right? It happened in 1952. Leon Harris, Jr., the vice president of the Dallas department store A. Harris & Company, offered George Grosz a major commission to commemorate the store’s 65th anniversary. Grosz arrived in Dallas in May 1952 and spent four days observing and digesting through sketches the people and mores of the city. Focusing the subsequent four months of time in his studio back in New York on Dallas, Grosz created a small body of four paintings and seventeen watercolors capturing his impressions of the city. In October 1952, the work was exhibited at the Dallas Museum of Fine Arts, then located in Fair Park. The current exhibition, "Flower of the Prairie: George Grosz in Dallas," gathers the same work not to recapitulate that exhibition of some 60 years ago, but rather to tell us with superb aplomb about the city of Dallas in the mid-twentieth century as seen through decidedly fresh eyes.

Before emigrating to the United States, Grosz made his name as a caustic critic of the Weimar Republic and its misuse of power. The Neue Sachlichkeit group of painters, in which Grosz was prominent, brought an empirical, if not raw eye to the dysfunction and corruption of Germany in the interwar period. While he moved his family to the United States in 1933, shortly after Hitler came to power, Grosz continued making images critical of the regime based on news.

There is very little sense of cutting Dadaist or Neue Sachlichkeit criticism apparent in the series Grosz created for his Dallas commission. The work is, instead, imbued with a sense of bedazzlement and awe. Grosz the Western European came to Dallas with preconceptions of a barely touched wilderness on the plains, cowboys and Indians, and a small town on the frontier. To his surprise, he was greeted by the Emerald City, a rising modern metropolis with urban-frontier types wandering its downtown cityscape.

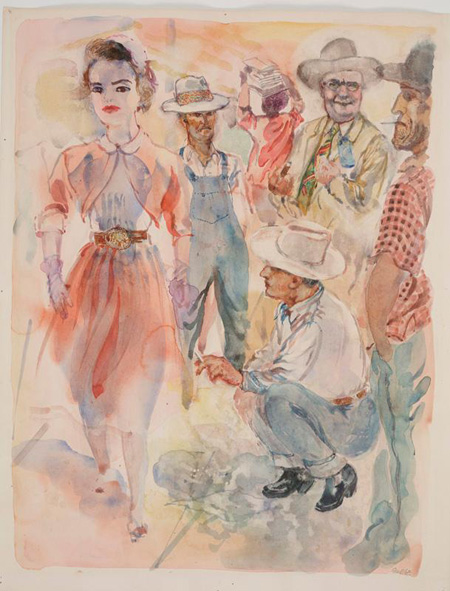

Grosz experienced the city from afar as a steel and glass wonder rising from the horizon, and from within as a teeming urban mass. Having seen the city from a bluff across the Trinity River, Grosz painted “Flower of the Prairie” in which the city’s skyline, dotted by rising skyscrapers, is a hot blue swirl at the center of a field of saturated yellow. “In Front of the Hotel” shows a small taxonomy of Dallas captured in front of the Adolphus, where Grosz stayed: a prim yet curvy woman, the hayseed, the cowboy on the make, and the backside of an African American hoisting newspapers onto his back.

If there is one place where the penchant for harsh social critique begins to be felt it is there, in Grosz’s few depictions of Black Dallas. “Old Negro Shacks” is a soft but telling watercolor of three tumbledown wood-frame houses. An African American man and little girl stand at the far right. They are about to cross the worn and broken macadam that is the street. Another watercolor, “A Glimpse into the Negro Section of Dallas,” shows the bustling retail side of Black Dallas in a crowded view from above onto a street in the Deep Ellum neighborhood.

Curator Heather MacDonald has taken a particular segment of Grosz’s work that is aberrant within the context his larger body of work, and situated the selection of works in the rich urban fabric of Dallas – its history and unique modernist sensibility circa 1952.