Continuing through September 29, 2012

The fetishization of fabric and flesh in Storm Tharp’s exhibition, "Holding a Peach," recalls similar fascinations in fashion designer-cum-film director Tom Ford’s cinematic debut, "A Single Man." The languorous affection with which Ford’s camera lingered on crisply starched shirts, cuff links, dress shoes, and bare flesh bathed in nighttime swimming-pool light, tipped the director’s hand as they celebrated sartorial finesse and homoerotic desire. Notably, Tharp is a cinemaphile whose passion for film informs the symbolism in his work. He has long lionized the Hollywood dandy; his stylized portrait of Clark Gable, on permanent view at The Nines Hotel in downtown Portland, is the pluperfect exemplar of camp-inflected matinee idolatry.

In a group show last year titled "Oompf…" Tharp unleashed a series of feverish drawings of male-on-male desire, most notably The unforgettable "No. 4." Two tacks from that work — clothes-horse foppishness and hot’n’heavy man-worship — converge in the sculptures and works on paper in the current show. Tharp, who gained international renown when his jolie-laide portraits were exhibited at the 2010 Whitney Biennial, now abandons the strict portrait form in his series "Spring Picture." The sixteen works on paper in this mixed-media series are variously appointed with ink, gouache, fabric dye, and gold leaf. They are not traditional portraits, but portraits of body parts and garments.

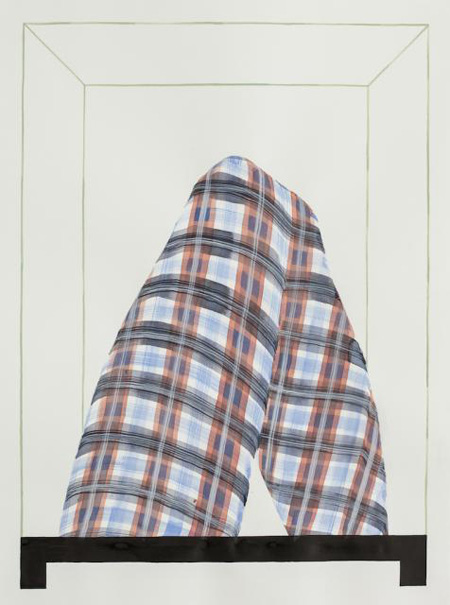

Each work has a subtitle that offers hints to its content. "Knee" shows the eponymous joint outfitted in skin-tight plaid pants; "Athlete" a male derriere in briefs and a belt; "Nude Beach" a hirsute torso slipping out of a yellow-and-white t-shirt; "Aristocrat" a hand reaching for a dress shirt; and "Jock with Veil" an odd admixture of athletic truss and wedding headpiece. These parts are not rendered realistically, but as surrealistic groupings of lumps, humps, and stumps — imagine a thalidomide baby outfitted alternately by Brooks Brothers and International Male. The subtle intricacy of their details, not apparent in reproduction, is striking: the feather-light strokes that read in aggregate as body hair, the vivid yellow of a shirt, the rosy tint of a nipple.

These forms are referenced in a series of sculptural works encased in pedestal-mounted vitrines, each of which contains a fabric-covered, three-dimensional representation of the drawings’ subject matter. With their terrycloth and dyed-fabric upholstery, they resemble eccentric pillows. Many are propped up by shiny brass sculptures with suggestively phallic contours. If Constantin Brancusi had designed sex toys, this is what they would look like.

The pillow motif recurs in a witty installation called "Grande Odalisque," a postmodern take on Ingres’ Mannerist-influenced masterpiece. Each of eleven pillows is emblazoned with a photographic reproduction of a part of Tharp’s body — hands, forearms, hairy chest — and laid out in a fashion to suggest a recumbent figure. The work serves as a cheeky updating and male appropriation of the harem-girl archetype of timeless chauvinist fantasy. In this piece and throughout the show, Tharp demonstrates a thoroughness and ease with diverse materials that is married to a slyly ironic approach to the dual romanticism and grotesquerie of human sexuality.