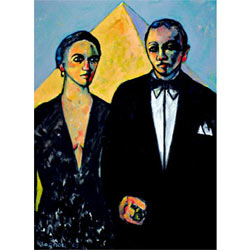

Phil Joanou, 'American Gothic', 2002, oil on linen, 40 x 30'.

Phil Joanou’s large and small figurative-based oil on linen paintings journey heroically toward an integration of the mind, heart and soul’s chaotic impulses and imagery. They do so with playful and clever winks toward well-known art historical precedents. Having worked for years in the advertising business, this Pasadena-based artist never succumbs to mere illustration, but rather applies his formidable skills as a draftsman in each work to fluid and expressive ends.

His version of “Birth of Venus” draws on Botticelli’s central image of the goddess of love emerging full-grown from a clamshell. Joanou, however, veers conspicuously from the Italian master’s theme of feminine purity and softness. In its place we find what at first appears to be a voyeuristic assault on women and the debasement of human sexuality in general to a fetishized commodity. But then there is a twist.

Rather than posing for the admiring gazes of the nearby angels as in the Renaissance canvas, Joanou’s Venus finds a Cannon-type camera aggressively thrust toward, almost into her. Where Botticelli’s spry and alert Venus balances herself erectly on a shell that has washed up on the shore of a refreshing sea, Joanou’s weary goddess and the calcified clam on which she reclines sink into a mob of surrounding tiny, granite colored and dry looking figures, symbolizing the coldness of the undifferentiated masses.

Women serve as both subject matter and muse for the artist in many of these works. Another painting titled “Women II” presents a woman sitting on a curvaceous couch, whose fabric and the room’s surrounding wallpaper erupt in a dance of decadent floral imagery. Unclothed except for a piece of fabric covering her loins,”Women II” references Matisse’s interest in the decorative aspects of art, as well as his and Gauguin’s fascination with women as exotic emblems. Joanou’s contemporary model, by contrast appears relaxed and self-confident about her body, and appeals to us through an appearance that is neither overly glamorous nor sexualized.

What’s more, Joanou’s woman turns the cliché of women as objects of the male erotic gaze on its head in a most inventive manner. Rather than being looked at, she stares both complacently and victoriously at a tiny naked man whom she holds literally in the palm of her hand. One can’t help but think of King Kong cradling Fay Wray, the distressed damsel in the 1933 movie classic. Size evidently matters now as it did then, but whereas in that first Kong film it was feminine “beauty that killed the beast,” in this painting the woman’s giant stature and its accompanying metaphorical power “kills,” or at least reduces the male ego into a pawn-sized figure quite literally at the mercy of this woman’s every wish and whim.

In “Nietzsche’s Dream IV,” Joanou traps the German philosopher inside a Euclidian box-like cage that floats in the air. Crouched, cramped, cowering and scared, this existential thinker who declared that God was dead and championed a “Superman” ideal of a person capable of relying on the intellect and power to transcend human weakness, may very well be wondering who in heaven or earth will let him out?

Published courtesy of ArtScene ©2009