Continuing through December 1, 2012

Despite its technical-sounding name, “Ant Farm Media Van v.08” looks as if it has been unearthed from a deep bog that caked it with the blackest mud. An actual 1972 Chevy van, it is entirely covered in a black, plaster-like material, even over the windows. Original members of the famed counterculture art collective of the 1970s, Ant Farm, would probably say - in the mellowest of tones - that it is what’s inside that counts. In fact, two members of the group, Chip Lord and Curtis Schreier, along with Bruce Tomb, created this 21st century reincarnation of the media van that so shattered conventionalities back in the day.

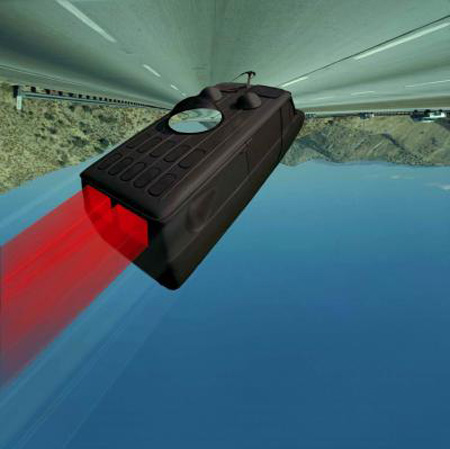

The Ant Farm Media Van of 1970 traveled the country shooting photos and video, installing inflatable shelters and offering the beginnings of performance art. The van was tricked out with the new video technology of the time and had a clear dome on the roof that served as a kind of open-road crow’s nest for the artists and architects in the collective. Inside the van was a small but working television studio, as well as lots of seating and a bed.

As the exhibit explains, Ant Farm was among the first groups to take advantage of video technology and guerrilla TV to conduct irreverent cultural critiques as part of their Truckstop Network Tour. But as they traveled their merry way, Ant Farm managed to create some serious art, notably, “Media Burn,” in which a customized Cadillac crashed through a burning wall of televisions, and “Cadillac Ranch” outside of Amarillo, Texas.

Flash forward to 2012 and the Ceramics Research Center across from the ASU Museum, where there is space to display the new media van as well as to pay tribute to the original Ant Farm through photos and video. This time around, the van has a name, HUQQUH, pronounced “hookah,” and the interior is spare in its accoutrements, with hard benches and a TV screen. Given how far technology has come in speed and miniaturization over the years, though, the simplicity makes perfect sense.

The visitor need only step into the van, called a “conversation pit,” and participate in creating the “ASU Time Capsule Triptych” by plugging in his or her own mobile device, be it smartphone, tablet computer, camera or music player. A small steering wheel with a screen on top gives way to various USB and other cables. To continue the “hookah” theme, visitors are asked to “give a toke” from their devices. When there is enough of a crowd in the van, friends and strangers create what the artists call a “social condition.”

The show has already had enough traffic to gather hundreds of digital files. When the show ends, the van will be sealed, like a time capsule, only to be opened again in 2030.

The Media Van’s debut at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in 2009 also spawned a time capsule, and a wall of thumbnail images from that show indicates that visitors like to share photos of family and friends, all kinds of music, scenic photos and random pictures of their surroundings at the museum.

The fact that the installation is interactive probably helps viewers engage with the anarchic ways of Ant Farm. But one leaves the exhibit wishing that it included even more archival material regarding the group’s history. Doesn’t the current, plugged-in generation need to know what a long, strange trip it’s been?