It sounds odd to say, but Karl Benjamin could not have passed at a better time. The widely revered painter and pedagogue, who died this past summer, had not produced work for over a decade, but he lived long enough to see his artwork, and that of his peers, honored as seminal phenomena and elevated out of the footnotes of history books. He also spent his last years, working or not, surrounded by younger artists who took great inspiration from Benjamin's ideas, spirit, and example. Here was a painter who worked neither in a vacuum nor in an art hub, was true to his own ideas even as he contributed them to a larger local--and ultimately international--discourse, and was directly or indirectly responsible for the education and dedication of several generations following his own.

Born in 1925, Benjamin was one of the oldest living faces of the Getty's Pacific Standard Time initiative, and also one of the proudest, and most respected. This was to a certain extent ironic, as his artistic origins had been humble and his standing always a bit lower than the rest of his cohorts', among whom he was the youngest. Of the other artists comprising the historic "Abstract Classicists" exhibition, only Frederick Hammersley was close in age to Benjamin, born six years earlier. The other two stalwarts of southern California geometric painting, John McLaughlin and Lorser Feitelson, were a quarter-century older. Helen Lundeberg, excluded from the show but part of the same tendency, was also Benjamin's senior. Benjamin would joke about his being the kid of the group--and about the fact that, in effect, he backed into doing art in the first place.

Having moved to the Inland Empire after his War service, the Chicago-born Benjamin graduated the University of Redlands in 1949 with a humanities degree, planning to be a writer. Already with a family, however, he took an elementary school teaching job in Bloomington, a poor San Bernardino County backwater. As Suzanne Muchnic relates in her account of Benjamin's life and work, published last fall on the occasion of the PST-related micro-survey mounted by Louis Stern Fine Arts, the young teacher set his wards to writing poems and short stories, but was also expected to have them make art. He avoided the requirement until he could no longer, finally passing out paper and crayons. He found the kids' pictorial fallback mode, full of houses and trees, prosaic and boring, so he instructed them to work just with colored shapes -- to "fill up the space with pretty colors," "don't mess around," and "shut up and concentrate." To his relief, they did. And to his amazement, he found the results engaging. "It was coming from the same place as the stories they wrote," he told Muchnic.

By 1951 Benjamin was himself following the instructions he'd given his kids. And he was exposing himself to all the modern and contemporary art he could find--little enough in the Inland region, not much more in Los Angeles, but plenty, at least, available through books and magazines. Locating a nascent art scene bubbling around the Claremont campuses, he moved his family there in 1952, and ultimately earned an MFA at Claremont Graduate School in 1960. He continued to teach on the elementary school level, however, until the 1980s.

You read right. Benjamin taught elementary school up until the '80s. And earned his MFA in 1960, the year after "Four Abstract Classicists" debuted at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and History. The exhibition, which traveled to San Francisco, London, and Belfast, put Los Angeles on the international art map for the first time, hinting to the art world that serious artistic discourse could and did maintain outside New York and Paris. Benjamin had been featured in a one-man show at the Pasadena Art Museum as early as 1954, but the show of what curator Jules Langsner called "hard-edged" painting found Benjamin far advanced beyond the still-referential, often Picassoid or expressionistic subjects he had showed in Pasadena. An entirely non-objective vocabulary had somehow emerged and taken over Benjamin's practice. Barely aware of the artists he was to be paired with, he hadn't been trying to fit into any local or international trend towards geometric abstraction; but, as he recalled to Muchnic, it was simply a matter of '[m]ore and more geometric forms... coming out in my work... I just kept working, trying to get the right line, the right color, hoping that something would gel."

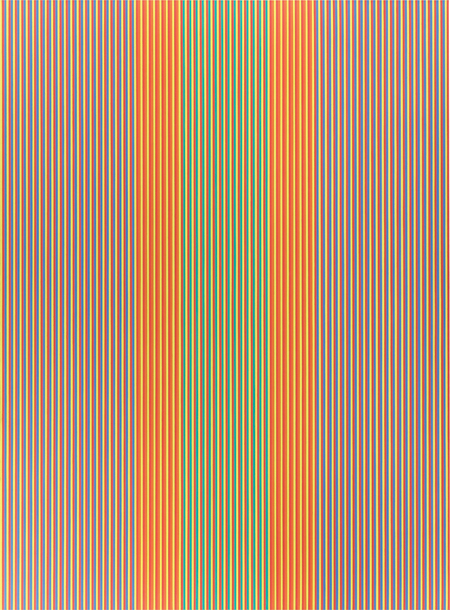

In discussing the "hard-edge" practice he'd identified among Southern California painters, Langsner noted that, "color and shape are one and the same entity. Form gains its existence through color and color its being through form. Color and form here are indivisible." If Benjamin's work up to 1960 had suggested this relationship, after 1960 it embodied it. For the next four decades his painting was all about color taking shape and shapes being colored, the trajectory of his oeuvre less about the evolution of a look--one format would give way, often suddenly, to a very different format--than the exploration of a vast but coherent practice. The shapes can repeat in intricate pattern or shiver into neo-cubistic facets; they can march across the canvas as identically proportioned stripes or they can settle into large areas floating against recessive fields; they can determine almost heraldic designs or they can divide the canvas into grids. Interestingly, what almost never happens is the repetition of color sequence: Benjamin seemingly sets up highly ordered compositional structures in order to disrupt them with colors occurring randomly. One looks, overall and in any single painting, for a broader logic to his color thinking, but it was invariably sourced in taste: a color in a particular unit induced a decision on Benjamin's part to place a particular other color (or occasionally even the same color) in the next unit. Benjamin's logic was the logic of the poet, not the statistician.

Well known throughout Southern California and honored here with exhibitions throughout his career (even when ignored by the rest of the world), Benjamin was not simply an Angeleno, but an Inlander. He came to play paterfamilias to myriad artists of all kinds who studied and settled in eastern Los Angeles County and beyond. Long after he had to stop painting and teaching for reasons of health, Benjamin still delighted in his interactions with his fellow artists, sharing his observations and experiences with them and providing them particular inspiration, no matter what style or medium they worked in. Abstract painters, of course, gravitated to Benjamin, finding their DNA in the work of this decidedly un-gray eminence and answers as well to their questions about formal rhythm and color relationship. Patrick Wilson, Lisa Adams, Alex Couwenberg, Barbara Kerwin, Fatemeh Burnes, and Alexandra Wiesenfeld--to name but a small, if stylistically diverse, coterie--were among those spurred by Benjamin's insight and advice, whether proffered in classroom or studio. But figurative painters, ceramists, installation artists, and all manner of artistic practitioners also received serious attention from the gentle, soft-spoken former K-12 teacher, enjoying precious access to his collections and recollections.

Overall, Karl Benjamin spent more time in obscurity than he did in the limelight, and that's one reason it was so gratifying to see him see himself and his comrades beatified in PST. But even when he stopped teaching and working, he never disappeared from the local scene, not for a moment. He was a "living monument" in a tentative art capital ever unsure of its own history, reminding us even when little else did that Southern California has its own complex and distinctive aesthetic legacy. A teacher his whole life, Benjamin embodied the pedagogical (if not the academic) impulse to artistic discourse in these parts. He went on his nerve, to be sure, but patiently taught others to do the same, providing them pointers on how to do so.

There were, and remain, other inspirational figures like this in Southern California, perhaps more, even per capita, than most. But Karl Benjamin personified an old school, where innovation resulted from workmanlike application impelled by curiosity--the well-behaved but no less inspired version of the surfboard or tattoo artist cranking away in the garage and showing neighborhood kids how to do the same. Benjamin wasn't a mad scientist, but a happy artist, and as such made us happier to be artists, too.

This article was written for and published in art ltd. magazine ![]()