The recent closing of the Seattle Art Museum loan show, “Elles: Women Artists from the Centre Pompidou, Paris” made me think of all the contributions women have made to Seattle’s visual arts culture. Seattle’s remote geographical location, its late flowering culturally, and its openness to eccentrics and outsiders, helped women artists and art administrators develop and flourish, rising to positions of power that many occupy today. I have had the pleasure and privilege of knowing most of them and developing as an art critic under their purview and supervision.

Because of underdeveloped visual arts institutions, everything was not already sewn up when I returned to Seattle in 1976 after living in New York City. Women arts professionals benefited, as did I, from a nascent art scene about to undergo a long period of explosive growth.

Today, all the Seattle art museums are headed by women and programmed by women curators, along with a majority of female art dealers, magazine editors, art critics and arts writers. Their presence and subsequent programming have shaped the visual arts audiences of the region and shaped the writings I have collected in four volumes of reprinted interviews, reviews and essays.

Not that the early days of art in Seattle were dominated by men anyway. While the city once prided itself on having had the nation’s first female mayor, Bertha Landes, the first art collections and museums were also founded by women. Emma Frye’s holdings of 19th- and early 20th-century German, Austrian and Scandinavian painting became the Charles and Emma Frye Art Museum, opening in 1952, eighteen years after her death. The widow of the Fryes’ estate attorney, Ida Kay Greathouse, succeeded her husband as director of the new museum, where she ruled for 38 years. Her anecdotes about buying trips to New York at the old-line American art galleries revealed to me that they did not at first take her seriously until her prescient purchase of a work by Mary Cassatt joined Emma Frye’s daring acquisitions of Lillian Genth and Hortense Trotter. Midge Bowman and current director Jo Anne Birnie Danzker succeeded Mrs. Greathouse. Collector and chief Mark Tobey patron Emma B. Stimson was SAM director during World War II.

An African-American woman, Zoe Dusanne, was the city’s first modern art dealer, joined after 1950 by Henriette Woessner and, after 1964, Francine Seders (still in business today). Women art dealers influenced me as an art critic because, depending upon what they showed, they determined about what and whom I wrote. Before current dealers Susan Grover, Lisa Harris, Young Chang and Phen Huang, the 1970s art scene was dominated by the legendary Linda Farris, along with Carolyn Staley and Diane Gilson, all three of whom could not have been more encouraging and supportive of a young art critic.

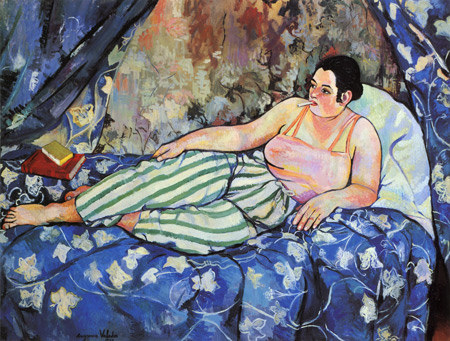

With debuts (for Seattle) of everyone from Louise Nevelson and Alice Neel to locals Sherry Markovitz, Norie Sato and Mary Ann Peters, these women brought new art styles and personal visions to replace the by then tired-out Northwest “mystics.” In so doing, they reinforced my own conviction that the Northwest School needed to be subsumed within American modernism and, for me, replaced by a concentration on abstract artists of the same period.

After a 1993 move downtown by the Seattle Art Museum, new director Mimi Gardner Gates (the Microsoft co-founder’s stepmother) anchored SAM until her departure in 2009. Backed by board president and New York School collector Virginia Wright, Gates oversaw a larger building extension and the huge open-air Olympic Sculpture Park, where SAM contemporary curator Lisa Corrin arranged works by Nevelson and Beverly Pepper around newly commissioned works by Teresita Fernandez and Louise Bourgeois. Gates also retained and hired women for all the top administrative and curatorial positions.

If all this were not enough incentive to younger women artists to move to Seattle, women also dominate the field of art criticism and arts writing. Margaret Bundy Callahan was the wife of Northwest School artist Kenneth Callahan. In addition to her contributions to Town Crier and Seattle Times, my research has led me to surmise that she also ghost-wrote most of her husband’s reviews while he was art critic for Seattle Times over a ten-year period. Following the Callahans at the Times, Anne G. Todd, Thelma Lehmann and Jean Batie preceded Deloris Tarzan Ament, Sue Ann Kendall and Sheila Farr. Similarly, Ann Faber, Sally Raleigh and Sally Hayman critiqued before Regina Hackett at Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Hackett ran a popular art blog after the print edition of the P-I closed but has since dropped out of sight.

With the closing of “Elles: Pompidou” at SAM (which was attacked, by the way, in the British newspaper The Guardian for temporarily replacing all the art by men in the permanent collection galleries with art by women), little has, in fact, changed. Women may not have been at the forefront of art in early 20th-century Paris, but in Seattle, they quickly came to create, if not direct, the art scene well into the mid-century and beyond, up to the present. It has always been thus and I wouldn’t have it any other way.

[The Editor's Roundtable is a column of commentary by our own editors and guest columnists from around the region. Their opinions do not necessarily reflect that of Visual Art Source or its affiliates.]