Continuing through May 12, 2013

In an essay about Eric Fischl’s early painting,”Barbecue" (1982), the comedian Steve Martin has some fun with the formalist analysis of art, as exemplified by scholars superimposing compositional triangles onto Raphael Madonnas: “This is supposed to illustrate the [geometric, abstract] solidity of the painting’s construction ... I can’t help but think that a woman cradling a baby creates a triangle shape every time, unless she were wearing a big flat hat, which would create a square ... I have seen paintings with no observable triangular structure in them, and they seem to be perfectly fine. So I’m not sure what we gain by pointing out Raphael’s triangle, except that it’s fun to do, and we get to discuss something other than what the painting’s about.” The wild and crazy guy goes on to poke fun of “negative space” and “psychological loading”; to mete our praise for the female derrieres so delectably rendered by the sculptor Canova; and to catalogue the features of Fischl's painting, which he owns. Its scene is recognizable from Martin's own 1960s adolescence in Orange County — tract houses, pools, palm trees, and family barbeques with psychological undercurrents — all good fodder for a teenager aspiring to creative nonconformity. He interprets the central figure of a fire-breathing teenager, ignored by his square (unhatted) dad and his frolicking topless mother (or sister) as “a portrait of the artist as a young man,” confessing to complicity with what Fischl labels “the profound anti-authoritarian aspect to our attitudes,” and praising the work’s “mystery; it continues to keep its secrets ... imply[ing] meaning that is greater than the explicit message of the work itself.”

It’s always fun to mock pretentious art jargon, and we who labor in the art-crit vineyards can take a joke. Martin as an American Cyrano in "Roxanne" may have declared, “We don’t get much irony around here,” but the art world swims in it, and being uncool is the gravest breach of protocol. But an hour or so spent at the small retrospective "Eric Fischl and the Process of Painting" leaves me with the unsavory task of playing the art jerk, of singing the praises of triangles and negative space, and differentiating between the mystery of art — immanence and imminence cohabiting the same visual space — and surficial or superficial mystification.

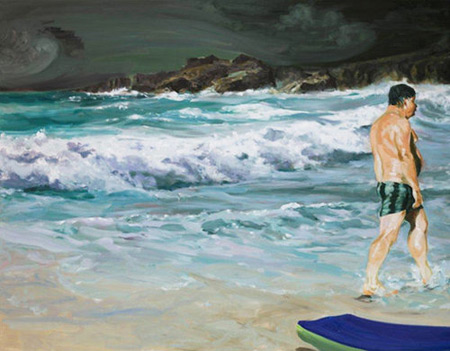

Robert Hughes described Fischl in 1988 as “the painter laureate of American anxiety in the eighties[,] ... documenting the discontents of the White Tribe [of] ... unreachable kids, grotesque parents, small convulsions of voyeurism and barely concealed incestuous longing” in their suburban “failed Eden.” Fischl came to prominence with Neo-Expressionism’s resurgence of figurative art, his loosely rendered sexual psychodramas, provocatively violating cultural taboos, and in doing so achieving notoriety and approval. In that climate, the artist’s lack of polish was no obstacle; it may have been interpreted as a token of sincerity. (At the time, figure painting was so taboo as to be unthinkable; Fischl recalls grad school as an “absolute zoo” in which one visiting professor memorably went onstage naked and tried to get an erection through hypnosis.) Fischl, to his credit, decided that painting the human figure was still a going concern. Unfortunately, after all these years, the paintings still alternate between the slapdash and the belabored, sliding, as Hughes wrote, between “assured colloquialism to ... awkward smearing and prodding.” The figures are neither realistic nor expressionist, but, unsettlingly, somewhere in-between, overly brushy and fleshy, as well as weightless and boneless; not distorted for deliberate expressive effect, as in, say, Egon Schiele or Alice Neel, but as if the artist could not discern their physical and psychological unreality. Some simply look unresolved. Fischl states, “I’m not interested in realism; I’m interested in drama,” but drama requires a suspension of disbelief and an emotional commitment from the viewer, and that must come first from the artist.

The narratives implied by Fischl's “soap opera ... cast of characters” fare equally insubstantial. Here’s the artist, in an interview, on the characters’ stories:

"So I take that body shifting some way, that head starting to turn, and I put that into a painting, into a context ... okay, are they looking at something or are they turning away from something? ... Is is something good? Is it something bad? Is it something meaningless? Or did a fly just land on their shoulder and they are kind of going like that? ... This person is turning away because they’ve just been rejected by something. What is it that they have been rejected by? Is it a lover or was it their dog? ... for me it’s not a preconceived narrative, it’s a discovered narrative."

The artist’s light concern becomes the viewer’s. The paintings thus live in the gap between figuration and abstraction without quite belonging to either (let alone to both): if the rendering seems wobbly, think about stories; if the stories don’t jell, enjoy the painterly painting. The painter’s casual ambiguity and ambivalence toward his own subject matter becomes clear in his discussion of another early painting, “A Visit to/A Visit from the Island" (1983), which was included in the earlier version of the show, at Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, but is not included in San Jose. This large diptych contrasts two views: on the left, sun-kissed naked Americans disporting themselves with speedboats and kayaks; on the right, Haitian boat people, imperiled by gloomy weather and rising waves, abandoning their dead. Fischl:

"… when I look at the people, the family frolicking in the beautiful waters of the Caribbean without a care in the world, I long for a stronger reality. I long for a drama. I long for a life-and-death experience that makes me feel alive. And so I paint these [boat] people, these heroes, these desperate people trying to find a better life. I see the toll it takes and it’s terrifying; all I want is to run back to the other side of the painting and be in this safe, comfortable, ridiculous environment of ennui … I can’t exist in either place for very long; that one is too terrifying, too difficult; that one is too ridiculous, too boring, and both of them make me want to run out of there. So I exist in the very thin strip between these two spaces."

There are some wonderful pieces in the show, such as “Untitled (Study for Year of the Drowned Dog)" (1983), an oil painting on four sheets of paper (as if the artist kept getting new ideas and expanded laterally, like a ranch house), displays a wonderful watercolor-like feeling for light and atmosphere, even if it employs what Hughes mocked as “artsy shaped-canvas garnish.” Bronze figures made from Fischl’s clay renderings of figures he’d photographed are surprisingly convincing. Source photos for a few of the paintings are on view as well, including shots taken at a nude beach in St. Tropez, one of which features the odalisque with Lolita sunglasses that would recur in many prints. There are erotic scenarios shot with hired actors in the galleries of a German museum for "The Krefeld Project," one of which includes artworks by Beckmann, Richter, Warhol and Nauman. The paintings made from single photographs, like the Krefeld paintings, make for more satisfying images, but at least one of the paintings composed on the computer, “Scenes from Late Paradise: The Parade" (2006-7), with its cavalcade of human flesh, suggestive of both Norman Rockwell and John Currin, manages to exploit its Mannerist artificiality. “Untitled (The Prices: Richard, Judy, Annie and Gen)" (2008), a composite portrait of the writer’s family, poolside, flatters nobody, though it boasts, to be sure, an aesthetically stable pyramidal Renaissance composition — and no square hats.