Back in December, when it seemed that even art-world nabobs like Dave Hickey and Charles Saatchi had somewhat ironically had enough of the commodification and corporatization of art, I ran across a list of fourteen questions that the veteran critic Irving Sandler was posing to his peers; and was foolish enough (having rolled my eyes at many a safe, bloodless review) to take them as a template for further investigations into the current art scene.

Today’s question, Sandler’s No. 1: What should art criticism be doing? Jonathan Swift in "Gulliver’s Travels" describes Laputan scientists as so “taken up with intense Speculations” on mathematics and astronomy that servants carrying “blown Bladders fastened like a Flail to ... a short stick” are hired to “gently ... strike with his Bladder the Mouth of him who is to speak, and the Right Ear of him or them to whom the Speaker addresseth himself ...” It is tempting to imagine oneself as one of these Flappers (for art), which I conceive to be the role of the critic, of course, but a fatal mistake. Art is as enthralling as any other form of intellectual speculation, but also extremely subjective, and always changing. History teaches us that it is almost a fool’s errand, fraught with art-historical head-knockings in an effort to accomplish more than utter vague approbations. Nevertheless, one must say (and post) something after taking up the Sandler gauntlet, and walk the risky meta-critical tightrope.

Writers who question the art world’s status quo are as valuable to its health as artists who question current art practice. A friend recently loaned me John Carey’s "What Good Are the Arts?," an informed and compulsively readable summary of the issues regarding aesthetic production which ends, by the way, with a long defense of literature, that bugaboo of both modernism and postmodernism. In the first half of the book, Carey, Chief Book Reviewer for The Sunday Times of London, considers such hoary grad-seminar questions as: What is a work of art? Is “high” art superior? Can art be a religion? Do the arts make us better?

The answers are, of course, ambiguous and contingent. Carey summarizes the aesthetic theories of Kant and Hegel, so dependent on Platonic idealism, and so long influential in Western art, that artists depict a transcendental poetic realm that is universally comprehensible — to persons of cultivated discrimination and innate taste, but not to the masses. In 1925, Ortega y Gasset described modernism, with its calculated insults to bourgeois taste in art, as serving the social purpose of dividing the hoi polloi from the educated elite, who possess “an organ of comprehension denied to the others.” As we all know, modern art triumphed, but at the cost of its vaunted outsider’s posture of moral superiority — and also of art’s aesthetic value as objects that are more than objects. The critic Arthur Danto locates this schism in 1964, with the appearance of Andy Warhol’s silkscreened simulacra of Brillo boxes that were indistinguishable from their models. What conferred the status of art would no longer be its visual qualities, but critical consensus, the acclamation of art-world insiders. Carey himself seems to adopt this democratic, through hardly populist point of view.

Of course, the problem today, with fashionably anti-aesthetic art-worlders embracing anything and everything in the name of political correctness — capitalism bad; inclusiveness good! — is that everything and nothing is art, which makes for the hawking of aesthetically null products: “investment capital,” in the words of Robert Hughes. Given this context I regard the job of art critics today, marshaling as much knowledge and self-awareness as possible, to restore some balance and perspective to art discourse, and not to exacerbate the aesthetic confusion. That is, is to save art from becoming irrelevant: just another status marker for the monied classes.

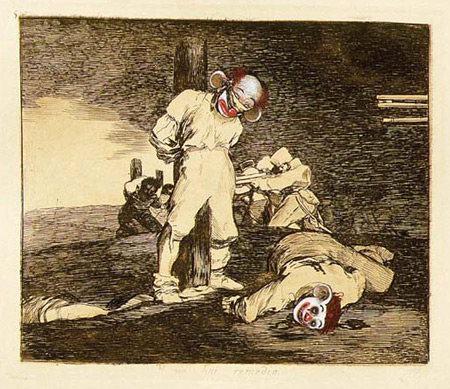

An anecdote from Carey demonstrates my point. In 2003, the artist team of Jake and Dinos Chapman acquired a rare set of vintage prints from Goya’s "Disasters of War" and painted clowns’ heads on them, incorporating them into a work entitled — ahem — "Insult to Injury." (Que barbaro! to quote Goya.) A self-described “comedy-terrorist” named Aaron Barschak threw red paint on the walls, the art, and one of the brothers, shouting “Viva Goya!” Carey: “He claimed in his defense that he was creating his own artwork, made out of another’s art just as the Chapmans had adopted Goya, and that he intended to enter his work for the Turner Prize. Finding him guilty, District Judge Brian Loosley said, ‘This is a serious offense of wanton destruction of a work of art ... a publicity stunt. Even by modern standards and even stretching the imagination to incredulity this was not the creation of a work of art.” The job of the critic is not to be uncritical; it may be, even, to keep art alive when so many forces are figuratively throwing paint, with sound and fury, meaninglessly.