Continuing through May 5, 2013

How a master of ambivalence can emerge as such a passionate voice, how a mix of humor and cynicism arrives at such clarity, how bitterness transforms into affection are mysteries that explain why the art world long underestimated Llyn Foulkes then finally embraced him. If a single artist's career trajectory was altered by Pacific Standard Time it was Foulkes'. Long respected, Foulkes was historically relatively marginalized because most everything fit, just not correctly. Most glaringly, the elements of Pop Art arrived late in his work, and once Warhol and company convinced us that celebrity culture could be celebrated (particularly if it offered witty references and critiques of the art world), he seemed to have it all wrong. In his adopted hometown, the young Bohemian never really took to his Light and Space contemporaries (despite brief early participation in the Ferus Gallery circle). Instead, he hewed closer to the Beat disarray of George Herms and Wallace Berman than the sleek purity of Doug Wheeler or Craig Kaufman. Essentially, the surf, car and aerospace culture most of the others reveled in made Foulkes want to puke.

This full dress retrospective turns out not to be "long past due" as admiring critics frequently say; it's actually perfectly timed. Laid out in conventional linear fashion, the curatorial mentality is that of a classic Hollywood biopic director. Starting with a photograph of the artist as a young man, eyes staring out at us with the same searing intensity as Picasso, the message is driven throughout that Foulkes and his art are bound together as one. The pair of introductory galleries take us back to his adolescent worship of Salvadore Dali with knock-offs that are cutely imitative (Dali's presence, like many elements of Foulkes artistic history, would return, embodied here by "Dali and Me" [2006]). Thank goodness Foulkes' early success was sufficient to sustain him but not so great as to propel him to the front of his class. Dali would never entirely leave his psyche or aesthetic, but Foulkes was not to echo his early master's descent into self-imitative promotion.

Lack of professional esteem has never been a problem for Foulkes. Once settled in Los Angeles in 1957 (as a student at Chouinard) following military service in post-war Germany and subsequently several years getting it out of his system with tough but aesthetically undistinguished existential despair paintings and assemblages, he discovered and fell in love with under appreciated areas of Southern California, such as the northwest corner of the San Fernando Valley. The rock formations there became a cornerstone of a long series of rag paintings. Fragments of sixties trends flow through this series, their scale drips with ambition and expectation, but ultimately both image and technique provide no more than a backdrop for what was to come.

Perhaps Foulkes' signature image is "Who's On Third" (1971-3), a self portrait whose face is covered by what might (or might not) be a denim rag with bloody red paint dripping down like straggly long hair to stain the artist's shirt collar. The send-up of a slapstick pie in the face (if he'd painted the rag as a pie tin, the blood would be cherry juice, think about it), together with the Abbot and Costello title are all yucks; yet the image is convincingly scary even now. It's not just the feeling that the paint is blood, it's the eradication of the posed figure's identity. The implication of wanton tragedy is palpable, but the laugh track is equally present and accounted for. The one element without the other would have been all bloated pretension on the one hand, derivative silliness on the other. For the first time that impossible balance between exceptional, dedicated self-discipline and abandoned self-indulgence comes into full view. All the basic elements were then in place on which Foulkes would build a remarkable body of work over the coming forty years.

What makes it all click, a volume of creative productivity that keeps getting richer with both expression and content, with a handful of culminating points in which Foulkes invested exceptional care and craft, turns out to be a single act of late 1970s skullduggery by Foulkes' former father-in-law Ward Kimball, a Disney animator. Kimball snuck a copy of the Mickey Mouse Club handbook to the son-in-law, who promptly concluded that the Disney media corporation had been brainwashing his and other American children into a sickening cultural passivity for years. With a somewhat paranoid sense of energy and purpose Foulkes has been delivering blows against the empire and its Mickey Mouse logo ever since, not to mention regular barbs at authority figures (such as Ronald Reagan ["The Golden Ruler," 1985] and generic local real estate developers ["Rape of the Angels," 1991]), heroes (the aforementioned Dali, Frank Gehry ["Portrait of Frank Gehry," 2011]) and, repeatedly himself.

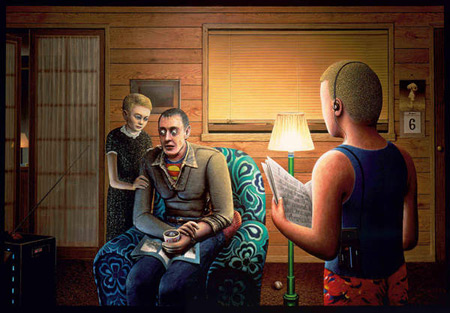

The tail end of the exhibition provides a crescendo that puts the show over the top. "Pop" (1990) and "The Lost Frontier" (1997-2005) are staged in their own dramatically lit rooms, each a rich, complex tableaux that summarize much of what has gone before without losing a bit of focus or intensity. The use of collaged elements gets ridiculously detailed, keeping the eye buzzing around for as long as you are willing. They masterfully render space well beyond their bas-relief surfaces, arousing the kind of fascination I used to feel as a kid visiting the Natural History Museum's diorama exhibits. The rage and disappointment stemming from Foulkes' certainty of our culture's irredeemable corruption and decline stands undiminished; but so too is his worshipful attraction for the landscape we have inherited, his love of the Three Stooges' slapstick and Spike Jones' musical humor (why his one man music Machine does not receive pride of place here is beyond me; perhaps the prospect of living without it for a few months was more than the artist could bear). That is why I'm pleased to see him get his due these last couple of years, now that he's pushing 80. If it all starts to make him flabby at this point then, Mr. Foulkes, you are entitled. You are now at the head of your class. Go be Dali if you want.

Published courtesy of ArtSceneCal ©2012