Sometimes, when I am writing, I get stuck and can’t seem to make a sentence work. Frustrated, I go into the kitchen to make a cup of tea. Inevitably, the shift in mental focus moves me past the sticking point and I figure out what to do with the pesky sentence that sent me there in the first place. So I leave the kitchen, return to the computer and continue writing. Hours can pass before I remember the tea water. I have ruined several teapots and burned untold number of pans by boiling the water away, which is pretty risky, since I live in a wood shingle bungalow. (I finally broke down and bought an electric water boiler, so writing rarely endangers my house these days.)

The point is that writing can put me in what Mihaly Csikzentmihalyi calls the “flow,” the state of total concentration — indeed, total absorption — in creative activity. As Csikszentmihalyi notes in "Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience" (1990), this creative state is also intensely positive. It can be characterized by joy, even rapture, while performing the task at hand.

Csikzentmihalyi began studying the flow more than thirty years ago, after learning about artists, particularly painters, who get so involved in their work that they disregard their need for water, food, or sleep. Fascinated by his ideas, I decided to speak to a few contemporary artists and see how they feel about the flow.

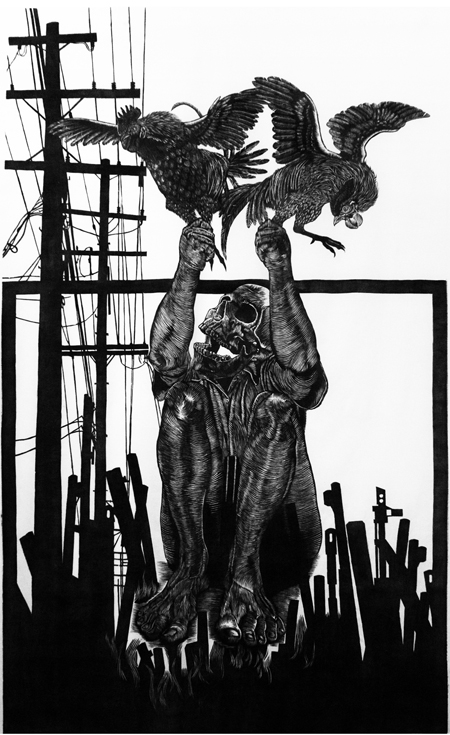

The first artist I spoke with was Abel Alejandre, whose immense woodcut “A Tale of Two Birds” was recently featured at Coagula Curatorial. I told him briefly about Csikzentmihalyi’s ideas and he started talking:

“My work is very meditative. Because it is very process-oriented, it’s easy to get lost. I happen to hypoglycemic, so what happens when I forget is I start feeling really, really weird and it’s like, oh that’s right, I haven’t eaten since yesterday. I often suspend the idea of time when I’m working. It seems like only an hour has gone by, but a whole day has gone by.

“’A Tale of Two Birds’ represents over 900 hours of work. I started with a study on paper. Then I transferred the drawing onto the woodcut by putting it face to face with the woodblock and rubbing it from behind with a spoon. Then I completed the drawing on the wood and began to cut. The wood fights you back. (Unlike linoleum, which cuts fast, like butter.) It’s a very, very slow process, like watching paint dry. I worked 12-16 hours a day for about three months. I didn’t take a day off.”

The woodcut is glorious; a ravishing image of skeletal figure holding up two battling roosters, their feathered bodies rippling with finely cut texture. The thousands of grooves cut into the original wood block provide elegant testimony to Alejandre’s laborious — and yet joyous — process.

Later that same day, I spoke with Mark Steven Greenfield, whose “Animalicious” series of ink drawings was exhibited at Offramp Gallery in March. Many of the works focus on old television and film images that deploy African American stereotypes, from blackface actors to cartoon characters. Behind and around them surge Greenfield’s signature textures, abstract concatenations that hover somewhere between elegant Islamic calligraphy and nervous doodles. Densely packed, the drawn textures are composed of hundreds, sometimes thousands of individually limned forms.

When I called Greenfield, he laughed, and told me a story.

“I’ve been involved in Transcendental Meditation since 1973, and periodically they recommend that you get a checking, so about a year ago, I went to see one of the instructors to get a checking. I was talking with her about my work and she chuckled and said, ‘A little known secret is that artists get into a meditative state when they’re doing their work. All kinds of beneficial things happen. Stress levels drop. It’s a by-product of doing the work.’

“And then she told me something particular to my work. ‘What you’re doing is manipulating the medium in such a way as to create individual mantras. Each of those little glyphs is a mantra. So when you create a field like that, you’re diving actually beneath the conscious and subconscious levels to the source of creativity. You are double-dipping daily. You mediate and then, when you make art, you go into the Universal Consciousness. And in that journey into the Universal Consciousness, you’re expelling stress and things that have brought trouble into your life.’

“When I told her I liked working between 12 and 4 at night, she said, ‘That’s Brahman time. Everyone else is in dream state, it permeates the atmosphere, and you’re just mining it.’”

Focusing back on the calligraphic fields in his work, Greenfield added, “It looks like it’s obsessive compulsion. It’s so consistent, it looks like I’ve done it in one sitting — which suggests obsession — but actually it was done over three months.”

Both of these artists — Alejandre and Greenfield — speak about their work process in terms that would be familiar to Csikzentmihalyi. Each relishes their intensely focused — and intensely pleasurable — time in the flow. Alejandre forgets to eat, Greenfield goes into a deep almost meditative state. Our artists are entering into Csikzentmihalyi's flow in equally distinct ways, which I'll continue to examine in my next column.