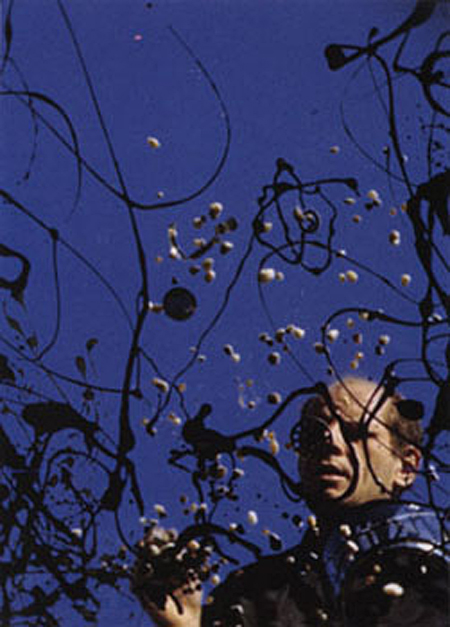

What did it feel like to be Jackson Pollock painting "Lucifer" in 1947 — what did his arms and wrists and legs physically feel like as he stalked the canvas, drizzling, dripping, and flinging paint? We’ve all seen Hans Namuth’s film footage of Pollock from 1950, with Namuth’s camera underneath a pane of glass, gazing up at the painter in the act of creation. And while watching that footage does afford an idea of the physicality of Pollock’s process, it can’t impart the actual sensations of what it was like to make that painting. The gulf between our experience as viewers and that of the artist during the heat of making work, will always be an unbridgeable divide — or will it?

I thought about this recently while playing the piano, something I do strictly as a hobbyist during those rare hours I’m not looking at, or writing about, visual art. The piece I was learning was one of J.S. Bach’s intricately contrapuntal "Two-part Inventions," and as I played it, it occurred to me that to play Bach fluently is to inhabit, if only for the duration of the piece, the mind and fingers of a genius. To play the work allows a far more intimate mind-meld with the composer than one gets merely from listening to a recording or live performance. It is thanks to the rather magical phenomenon of musical notation that musicians may travel through time to temporarily approximate the composer’s own experience of creating a given piece.

Similarly, the notation of dance choreography allows contemporary dancers to replicate the movements predicated by Nijinsky, Balanchine, Cunningham, and Fosse. And in the realm of literature, if one is inclined (as was gonzo journalist Hunter S. Thompson during his formative years) to transcribe — that is, to physically type out — the novels of Fitzgerald and Hemingway, one may experience the sensation of brilliant sentences issuing from one’s own hands, in the hopes (as Thompson believed) that the very act would osmotically improve one’s own writing.

Such notations and transcriptions are not currently possible in the visual arts, but we may imagine a time in the near future when virtual reality programs could approximate real-time creative acts. A painter, draftsman, sculptor, or video artist, for example, might be able to “record” their exact movements in a fashion that could be “played back” in our own bodies for didactic or recreational purposes.

Virtual reality hardware and software already exist to help golfers improve their swings and musicians to perfect their techniques. Flight simulators replicate the experience of flying a plane, while tank simulators have become an integral military tool. For now, though, didactic technology for artists is ploddingly primitive. We can “Paint by Numbers.” We can pull up the late Bob Ross on YouTube and follow his formula for “happy little trees.” We can watch California painter Albert Contreras’ video (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=17z4cyOCsI0) instructing would-be minimalists how to create their own “X” paintings. Sol LeWitt famously created detailed written blueprints for preparators to execute his wall drawings, but his purpose in so doing was anything but the transfer of subjective artistic experience.

Until technology reaches the point that the Leonardos or Brancusis of tomorrow can don full-body recorders as they create masterpieces for the hoi polloi to re-experience, laypeople will have to content themselves with appreciating art the old-fashioned way: by looking at it. That’s probably a good thing, given that technology leads as often to dystopic ends as often as it renders beneficial ones. There is a fair chance that the artists recruited to create virtual-art simulators will not be the Leonardos of the future, but the Thomas Kincades. I hope to be long in my grave before that brave new day dawns.