Continuing through October 20, 2013

Going back and thanks to the incandescent music of Bob Marley, Americans have been able to name a single spiritual movement native to the Caribbean, Jamaican Rastafarianism. Long before, victims of the West African slave trade brought their native Yoruban religion to the region and gradually adapted Catholic and Native American components to shape what became Santeria, a deliberately patronizing name bestowed by Catholics who regarded their sentient property as celebrating Saint Days in a childishly deviant manner. In fact the sons and daughters of Africa were celebrating the Yoruban orisha deities, but disguised so as to fool the white priests and slave owners.

"Things That Cannot Be Seen Any Other Way" traces the career of Havana native Manuel Mendive from tame but vigorous student work of the early 1960s to mixed media paintings and sculpture, as well as masks, body painting and video relating to fresh new performances. Mendive's rise to prominence began with a period of tight little folk-style paintings of the late 60s and 1970s that are rich but probably would have ended up as quaint tropes or curios had he not found his way to the far looser, bolder, more poetic visions that he graduated to in the 1980s and 90s.

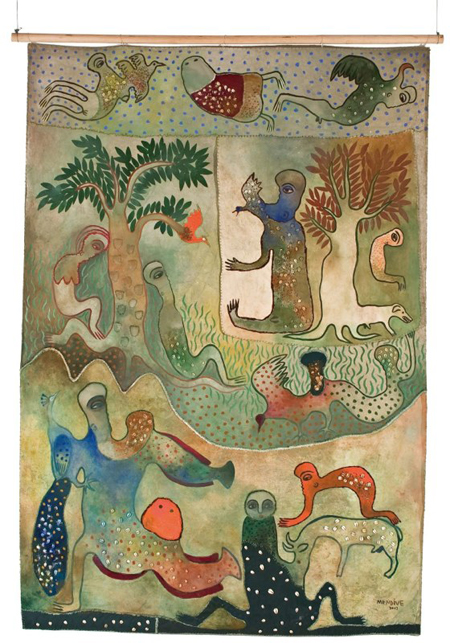

In the recent "Pan Sagrao (Secret Cloth)" (2010) the orisha figures blend human and animal elements in compositions that arrange them in rows and blocks, like loosely arranged tales to an overarching narrative. A large flap in the upper right portion of the work may be lifted to reveal additional figures in storybook fashion. Mendive deploys attractive and fluid blends of color and surface decorative elements, both painterly and affixed (particularly, at times to predictable excess, cowrie shells), all as an extension of his religious practice.

There is a clear path of creative development curated into the exhibition that reflects a series of leaps of both creative freedom and artistic ambition. Throughout, a seriousness of intent - to both convey and preserve a spiritual tradition - mixes effectively with a playfulness of invention that keeps us receptive to the flow of images and eager to see where he takes things. This is not only exhilarating, but also reflective of the artist's increasingly influential role as a spokesman for his religion, and a legitimizing force for it within Cuban society and beyond. In the end the power of Mendive's aesthetic lends substance and legitimacy to his beliefs, but what it really sells is him. Seems like a fair deal to me.

Published courtesy of ArtSceneCal ©2013