Continuing through August 18, 2013

Painter-fisherman, visionary, and genius are words that Forrest Bess used to describe himself. Like most visionaries, his life and paintings are so intertwined that it is impossible to separate his work from the circumstances of his life. Born in 1911 in the small town of Bay City, Texas, to a father who worked in the oil fields and a housewife, Bess never really fit into small-town life. He was interested in art early on, but his parents refused to let him pursue it as a career, so he agreed to study architecture. When Bess got to Texas A&M and later the University of Texas, he spent much of his time in their libraries, reading on a wide range of subjects that included the writings of Sigmund Freud, Charles Darwin, Greek mythology, and human sexuality. Throughout the remainder of his life, Bess continued to read prodigiously and write prolifically, if privately (there are 25 boxes of his letters).

Leaving college without a degree, Bess spent time in Mexico looking at the murals of Diego Rivera. He settled for a time in Houston, where he established a cooperative gallery with a group of local artists. When the U.S. entered World War II, he enlisted in the military. One night, after drinking heavily, Bess revealed his homosexuality to another man and was beaten badly, sustaining a serious head injury that may have contributed to a psychotic break. After that he had terrifying hallucinations, and an army psychiatrist suggested painting these visions as a way to cope with them.

After Bess’s discharge from the army, he ended up at his family’s bait-fish camp on the Gulf of Mexico near Bay City. There he lived in poverty and isolation for the next 20 years, making a meager living by selling bait, fishing, crabbing, and marketing the occasional painting to friends or through Betty Parsons’ Gallery in Manhattan. He met Parsons in 1948 on one of his rare visits to New York in search of a gallerist who might be interested in his work. Parsons, a former painter, showed American abstract art but also exhibited ancient and primitive art because she believed the two had much in common. She took Bess on, and he had his first solo show there in 1950. She continued to show his work every few years until 1967.

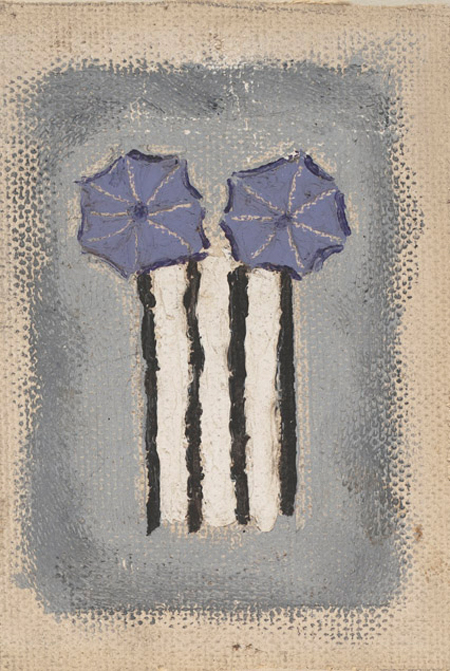

Bess was a self-taught artist who created highly symbolic, mostly small paintings. Emulating his historical mentors, Vincent van Gogh and Albert Pinkham Ryder, he built up thick layers of paint, sometimes with broad strokes of the brush and sometimes with dabs of paint. Most of his paintings feature a strong figure-ground composition rendered in either contrasting colors or black and white with just a touch of color.

“Dedication to Van Gogh” is reminiscent of Van Gogh’s “Wheatfield with Crows” in composition and brushstroke, but Bess’s painting is much simpler. He paints a black sun against a white sky, while Van Gogh places a pair of pale blue suns against a dark blue and black sky. The zigzag of Bess’s field is a combination of Van Gogh’s wheat and the black crows.

In his letters and notes, Bess created an entire alphabet of symbols that he believed were the basis of all artistic expression. Becoming familiar with these symbols can lend insight into his work, but it is not essential to enjoying the paintings. Many of these symbols relate to sexuality, which preoccupied Bess. A young man is represented by the sun, a young woman by the moon, a penis by a snake, and an eye by an orifice. The catalogue contains the keys to 46 of his symbols.

This is the first museum exhibition to focus on Bess’s work in more than 20 years. It includes 40 paintings in a small room along with three glass cases, which display a selection of the artist’s letters, writings, and photographs. It includes a fragment of his “thesis” (now lost), a theory that the unification of both male and female within one’s body can produce immortality. Bess experimented with his own body, performing several operations on his own genitals in an effort to become a hermaphrodite. Before and after photographs of his penis are presented in both the show and catalogue.

Many of Bess’s paintings are untitled, but the titles that do exist provide clues to what the artist was thinking. “Premonition” is composed of three ominous figures, one of which seems to be holding a sharp, white sword-like form. “Bodies of Little Dead Children” has two boomerang shapes lying on a dark background. In “Untitled (The Spider),” also reproduced on the cover of the catalogue, thin white lines on a red ground emerge from a small white circle and run off the canvas in every direction. In many of the canvases, various shapes seem to be swallowing or penetrating one another.

Perhaps the most common organizing principal in Bess’s work, however, is the landscape. Many of the paintings contain a horizon line, and some, like “Untitled (No. 11A)” even have wavelike forms. This is understandable, given the amount of time Bess spent outside, either on or near the water. His letters often include comments about the weather, essential information for one who earns his living from the sea.

In 1961, Hurricane Carla destroyed not only the fishing camp where Bess lived but many of his paintings as well. As she swept away his home and work, the storm seemed also to remove his lifeline to reality. He moved into Bay City, and things were never quite the same. Bess continued to be obsessed with his hermaphrodite theory while painting less and less. He drank heavily and was committed to a mental hospital in 1974. After that, he resided in a nursing home and could no longer paint, eventually succumbing to a stroke late in 1977.

For Bess, like most self-taught artists, there is no life without art. These paintings are small but they are intensely powerful, and the raw images are open to multiple interpretations. He spills his dreams, visions, and hallucinations onto the canvas, and the viewer is left to ponder them as best he can. In the words of curator Claire Elliott, “His legacy lives as a powerful argument in favor of art not as a solution but as a way of seeking.”