Last December the art critic Irving Sandler posed (www.brooklynrail.org) fourteen broadly philosophical questions to fellow art critics who are trying to understand where art is going. Today, the third question, Q3: Is there a crisis in art criticism?

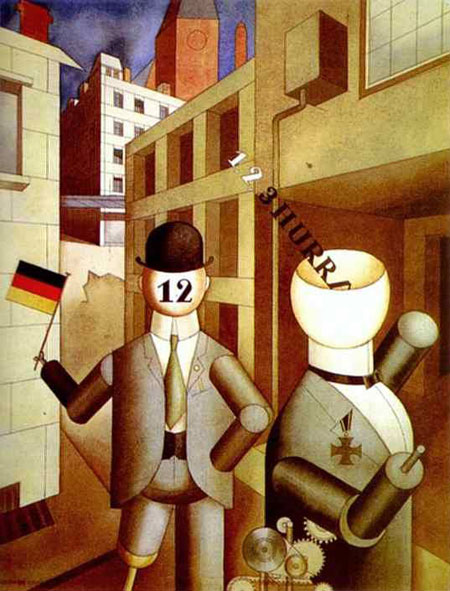

Well, yes, sort of. But first a trip down Memory Lane. In 1925, the Dadaist/Expressionist George Grosz and the publisher Wieland Herzfelde (brother of the photomontage artist John Heartfield) published a diatribe against the avant-garde art of the time, which they considered out of touch with reality, and a defense of Dadaist sociopolitical iconoclasm, entitled “Art is in Danger,” referring to the alarums of “foes of Dada.” It’s a pithy, funny rant, and partisan in the extreme, excoriating the “the head-in-the-clouds tendency of so-called holy art, whose disciples brooded over … the ‘really’ revolutionary problems of form, color, and style … while the generals were painting in blood.”

If we, a century after The Great War, now oscillate between holy art and aesthetic iconoclasm, and often confuse the two, well, there’s nothing new here under the global capitalist sun, either. Grosz and Herzfelde: “Formal revolution lost its shock effect a long time ago. The modern citizen digests everything ... [I]ce-cold, aloof, he hangs the most radical things in his apartment. ... Rash and unhesitating acceptance so as not to be 'born yesterday' is the password ... [C]ool, objective to the point of dullness, skeptical, without illusions, avaricious, he understands only his merchandise, for everything else — including the fields of philosophy, ethics, art — for all culture, there are specialists who determine the fashion, which is then accepted at face value. Even the formal revolutionaries ... do fairly well, for, underneath, they are related to those gentlemen, and have ... the same indifferent, arrogant view of life.” (That Grosz later repudiated his words, or at least depicted his earlier radicalism with irony, does not invalidate the 1925 analysis.)

The worldview of the consumer, or more richly the flâneur, pervades the art world, and it’s no good pining for “holy” art again, in either its realist or abstract incarnations. But to the extent that art exercises an influence on us, even shapes us, we need to be conscious of the values that it embodies, and what pleasure (or pain) centers in our brains it stimulates.

If there is a crisis in art criticism — and I say there is — its cause is the crisis in art at present. There is no consensus about its purpose or function beyond being a marker of social status. Art criticism for the most part divides into formalist exposition and description without analysis, or politically correct tendentious tract. This is because meaning has been leached from art in the name of total creative freedom, a phrase that has become a misnomer.

In the interactive age, viewers of art ironically play little role except as passive audience. Today we are conditioned to invest blind faith in the artist and the art world, at the risk of seeming culturally retrograde. The last domain of free thought that many of us saw in art once upon a time has gradually become (or is in danger of becoming) an entertainment for the fashionable conformist: what Aldous Huxley in "Brave New World" labeled Centrifugal Bumble Puppy. That is the crisis in art, which is reflected in art crit, and more broadly it is a reflection of contemporary society. We cannot afford to remain arrogantly above and indifferent to — and perpetually distracted from — this critically important crisis at our doorstep. Art can still be part of the solution; it should not exult in being part of the problem, or to participate in covering it up.