I’m not sure why everyone has their knickers in a twist over the possibility that the Detroit Institute of Arts might auction off some of its collection to assist Detroit defray an $18 billion deficit, one that has put the city into bankruptcy. Deaccessioning art has been standard practice for so long as to be an integral part of the museological landscape. I live in Chicago, and since 1990 the Art Institute of Chicago has deaccessioned paintings by Picasso, Braque, Matisse, Chagall, Renoir, Monet, Modigliani, Degas, and many, many more. Packed them up, shipped them out, and disposed of them on the art market. They’re gone; more accurately, they’re gone from Chicago.

That’s the way it works — it might be the museum world’s dirty little secret, but trust me, all museums deaccession, it’s happening where you live, in the museum you love, amidst the permanent collection you always thought was, well, permanent. It’s how museums prune their collections, dispose of duplicate material, etc. (And, as far as I can tell, with little of the art world outrage that has surrounded the current Detroit story.) But there’s a fig-leaf for museums (one less in play in the current conversation about the DIA). When the Art Institute of Chicago or a similar institution sells a Picasso from its permanent collection at Christie’s or the like it is obligated to use all of the funds it accrues — and these can run into millions of dollars — solely in its acquisitions budget. In other words, institutions that are members of the American Alliance of Museums (AAM) have agreed never to sell works from their permanent collections to pay salaries or operating budgets, but are free to deaccession to amass funds to buy that Malevich or LeWitt they’ve always coveted.

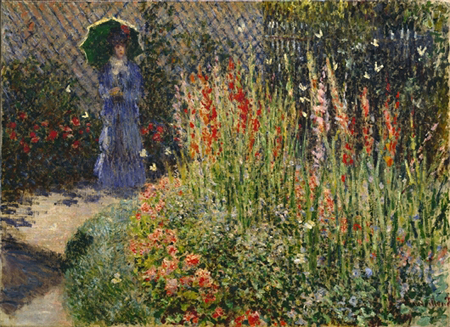

I support deaccession, as long as it’s transparent and fully thought through by curatorial departments and the like. It can be risky (in 1985 the AIC deaccessioned a work they valued at $20,000 by, in their opinion, an unknown follower of Francois Boucher to a dealer who then proved it was an original Boucher worth perhaps fifty times as much) and most museums end up with some egg on their face sooner or later. To me, though, it’s a kind of recycling. If a museum has 30 paintings by Monet (the AIC currently owns 33), why not provide another museum or collector the opportunity to purchase the one your curators believe is the least significant, and in so doing get the funds to buy that Tissot or Morisot that will make your collection broader, richer? The Monet (which wasn’t on public view anyway; not all 33 currently are) isn’t damaged or destroyed, it’s just moved, and if it ends up in Atlanta or Liverpool, why shouldn’t another audience get to enjoy it? I know the AAM regulation is really just pretense, that the funds raised by selling works of art are still used to free up other funds then directed to salaries and operating costs. It becomes somewhat of an actuarial sleight of hand permitting museums to claim their deaccession income is segregated in a lock-box.

Back to Detroit, though — because the fig-leaf of selling permanent collection art to raise funds for acquisitions isn’t at play here — my conclusion is that since that city is in bankruptcy, in fiscal extremis, and as citizens and businesses and tourists are all going to be asked to help, to make sacrifices, why shouldn’t its art museum? Does anyone really believe that the DIA would no longer be a great art museum if they carefully deaccessioned about five or six works — choose among their great Poussin, Van Eyck, Caravaggio, Brueghel, Bellini, Cezanne, Bronzino, Van Gogh, or many others — and raised and then chipped in about $1 billion of the $18 billion Detroit owes? What’s wrong with a museum functioning as a good citizen in a time of crisis? Those paintings, all of which somehow left collections in Europe to come to Detroit in the first place, would just move on to another life somewhere else. Are museums frozen tight, never to evolve, mausoleums for art, or might a little interior ebb and flow actually be interesting, and freshen the eye? I hear no one suggesting that the DIA’s entire collection should be sent tomorrow to Sotheby’s for immediate dispersal (though such an act could theoretically bring in more than $18 billion — what’s the opening bid for their Diego Rivera murals?). But if your community is dying you have to consider what you can do to help it survive. If the Art Institute of Chicago or your local art museum can (and did, and will again) sell something like a first-rate Braque, why can’t the Detroit Institute of Arts sell a first-rate Brueghel? Why?