Continuing through October 12, 2013

The face serves as the dramatic center of interest in the larger than life sized canvases favored by Eric Pedersen. His series of "Sleeping Giants" have, as the unifying title suggests, their eyes closed. They might be standing, but details of body language convey the passive recline of each model without the need to depict the bed or other surface on which they lie prone.

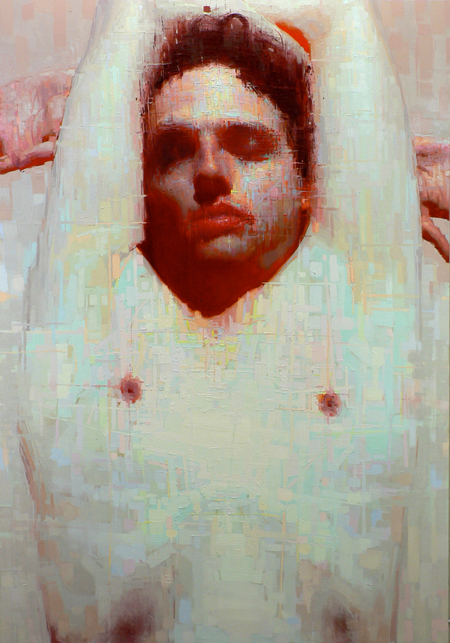

Pedersen alternately pushes the model's face to the very front of the picture plane, offering no spatial context beyond its relative position as it gets in your face (for example "The Untitled Painting of Aaron Half Asleep"); and pulls back to include the pale upper torso ("The Untitled Painting of Jonny Sleeping"), which serves as a foil to the deep set eyes, flame red hair, or dramatic shadow that separates, even beheads the sitter from the rest of their body. The contrast is both sexy and classic, setting off a pleasurable visual and visceral tension.

But the artist has a more profound issue in mind, arriving at not so much a portrait as "an arrangement of countless moments, events and experiences" suggested analogously through a layered network of brush and knife pyrotechnics. The series of poses depicting the sleeping model (or "half" sleeping state, whatever that might mean) is arguably a gimmick that rids Pedersen of the need to contend with movement, psychological or emotional expression, or interaction between artist and model. What I see, however, is a deliberate objectification of the person into a vehicle for the artist to meditate on the connection between physical appearance and animating spirit. In short, brushwork and observation functions as the pure means of reconstructing humanity. It is a bit like performing an oratorio with a solo guitar and vocal.

The trap of these images is therefore their facility. If that is what they are about, the formal problem (the single face and body in repose) lacks sufficient interest or degree of difficulty to impress. That is not to dismiss the elements of physical presence and atmosphere that Pedersen executes with aplomb. Still in his early thirties he has demonstrated these chops for years already. The crisscross flickering of paint application, therefore, is not only obvious, and commendable for the honesty of that, it must be only the opening salvo to a far larger project. If, that is, the ambition here is genuinely aesthetic.

Let me prop this work against perhaps two of our most fully realized historical models, each of which offers Pedersen a target that he may fire away at for some decades. Monet's brushwork, at its best, remains far ahead of almost anyone's because it is so unpredictable to the eye yet convincing in the resulting image it produces. It suggests a remarkable energy of engagement together with a magnificent technical skill in its visual resolution. Pedersen's hand operates primarily in a crosshatch manner that, yes is gestural, but by comparison to this master it is both limited and repetitive. There is a good deal of interest for the eye to take in, but there remains a good deal of distance yet to be made up.

A very different ambition is expressed in the work of Chuck Close. An essentially photographic image is built on a grid structure, with each square of the grid itself functioning as a singular image. Pedersen does not exactly take his brushwork in this direction; it is more a thatch work of lines that draw passing attention individually, and work more as a collective visual hum. But he makes this point in the quote cited above: Pedersen wishes to acknowledge the atomized bits that ultimately add up to an individual identity.

When the visual model of the pixel first gained an aesthetic foothold during the 1980s, the idea that extremely supple wholes could be constructed from essentially simple bits was a revelation that continues to echo throughout the art world. Pedersen, and his generation perhaps, are beginning from a different place that makes it clear that far from nearing exhaustion, we are only beginning to attack the complexity of one of art's key challenges.

Published courtesy of ArtSceneCal ©2013