Continuing through January 12, 2013

Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller have long crafted space, whether physically manifest with plywood and façade, or immaterially delineated by recorded audio. That space is often a surreal or dreamlike place reminiscent of an empty de Chirico piazza with the sound of children’s laughter echoing in the distance. Cardiff first gained attention with her audio walks in the 90’s, where the viewer put on headphones and ostensibly was guided along a path, but the “tour” was complicated by overlaid audio tracks – snippets of intimate dialogue and ambient noise. The shivery result was the feeling that the viewer had just slipped into somebody else’s skin and intrigue for a few brief minutes. Miller’s solo practice included more electronics, robotics, and surveillance in both a futuristic and nostalgic sense. Together, Cardiff and Miller are deft manipulators of perception and makers of immersive environments. They have created an impressive oeuvre that is ripe for a more complete retrospective. In the meantime, this exhibition, "Lost in the Memory Palace," is a purposeful and concise selection of “room works” spanning 18 years of collaboration that provides a chronology of a diverse range of shapes of space.

Although "The Paradise Institute" (2001) and "Forty Part Motet" (2001) are notably absent, viewers will discover that this show is greater than the sum of its parts and is, in fact, deliberately curated to be an experiential installation as a whole. The Museum has been transformed into a maze of sound corridors and isolated rooms, each containing a single work: a labyrinth intended to provoke wandering and perhaps, a little disorientation. The title of the show aptly references the “memory palace” of the title, a mnemonic device in which a person creates a place or series of places in his mind where he can store information that needs to be remembered. This exhibition can be explored as a tangible memory palace in which every encounter with a meticulously scripted installation is sure to trigger some kind of transmogrified awareness.

The earliest work, "The Dark Pool" (1995), is a memory palace in and of itself that clearly speaks to the obsessive art mind. A cluttered room is carpeted with flattened cardboard and made claustrophobic by makeshift desks on sawhorses covered with stacks of books and dirty tea cups (science experiments?). The viewer’s motions inside the room activate fragments of music, noise, and a story that never quite coalesces. The disjointed and unpredictable audio combined with the sheer quantity of detail of fictional pseudo-scientific memorabilia adds up to a dream-like encounter.

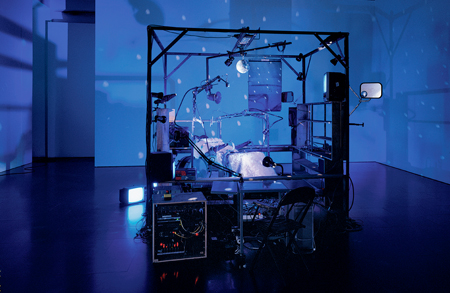

On the other hand, "The Killing Machine" (2007) is an open-walled installation that cannot be entered; the viewer is directed to push a button, which activates what appears to be a torture chamber. Implicated by the start button, the viewer cannot then stop the two large robotic arms that begin a choreographed interpretive “dance” over the empty reclining doctor’s chair; first they hover, then they jab and then drill. Although the impulse of this piece may have been the Abu Ghraib incident during the Iraq War, the theatricality of the piece operates more as sci-fi than an indictment of the horrific spectacle of war. As such "The Killing Machine" forcefully shifts our perception of reality. The sequence of clinical horror is muted by the sense that the enlivened machinery is forever re-enacting a sequence with no real consequence. Since there is no element of surprise, the YouTube video of the installation is as spine-chilling than the real-time experience of the installation. In an era where value can be defined by number of hits, this piece lives on and lives well beyond the museum.

Among the six installations, only "The Muriel Lake Incident" (1999) utilizes binaural technology, a method of recording that produces astonishing fidelity by using microphones in the ears of a dummy head. The viewer stands in front of a diorama of a theater (perfectly to scale) and dons the headphones while watching a video projection on the screen in the miniature cinema. The recorded ambient sounds of a large theater are cunningly layered on top of the soundtrack for the “film.” The audio is so life-like that when an invisible neighbor leans in close and whispers in your ear it feels authentic. Via the audio, the viewer is propelled into the miniaturized space and locked in engagement. Here, as Bartomeu Mari has described it, is an “audio event akin to sculpture.” The space is not so much the plywood box on legs containing the theater, but more the sonic reality projected into the viewer’s mind. A precursor to the award-winning "The Paradise Institute" (2001), which was originally produced for the Canadian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale, Cardiff and Miller continue to mine this rich vein of fabricating an immersive space to house an experience.

Published Courtesy of ArtSceneCal ©2013