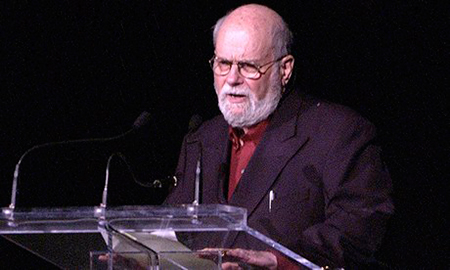

The recent death of philosopher and art critic Arthur Danto was met with sympathy and deserved respect from the art community, a group not generally associated with sober exequies. Danto’s illuminating, gracefully written columns for The Nation examined the contemporary art scene from a broad cultural perspective, combining both curiosity and catholicity, and eschewing the didacticism and moralizing of some of his colleagues. He was an informed but non-judgmental Virgilian guide to the various circles and spheres of art heaven and hell, ”cheerful[ly] eclectic” as Ben Davis writes, in “What Arthur Danto Meant to Me” (http://www.blouinartinfo.com/news/story/977502/what-arthur-danto-meant-to-me). Central to Danto’s legacy is the philosophical epiphany he experienced while contemplating the "Brillo Boxes" of Andy Warhol in 1964:

"… the moment when ... he first became able to see art as the territory of philosophy. How do we know, walking into a gallery, that Warhol’s 'Boxes' are artworks and not actual boxes of scouring pads? The answer, Danto posited, was that we couldn’t be certain without the intervention of thought: “To see something as art requires something the eye cannot descry — an atmosphere of artistic theory, a knowledge of the history of art: an artworld,” he wrote in an essay called "The Artworld" (http://www9.georgetown.edu/faculty/irvinem/visualarts/Danto-Artworld.pdf) in the Journal of Philosophy, also in 1964. “What in the end makes the difference between a Brillo box and a work of art consisting of a Brillo Box is a certain theory of art.” Theory was all; the thing was nothing — or rather it had now become so."

Davis, not surprisingly, sees today’s pluralistic (and chaotic) artworld, in which no aesthetic theory prevails, as the reification of Warhol’s concept of art as business, disseminated and given intellectual cachet by Danto:

"As a viewer, you had to speculate more and more about the artist’s intention in order to make sense of what was going on. Finally, since you could not say that one artist’s 'feeling' was really better than any other’s, it became clear that there was no common artistic project, no shared criteria to judge by. You could be interested in Raphael and Caravaggio, or you could be interested in comic books and Brillo box packaging, or both — whatever floated your boat."

“The age of pluralism is upon us,” Danto says towards the finale of the “The End of Art.” “It does not matter any longer what you do, which is what pluralism means. When one direction is as good as another direction, there is no concept of direction any longer to apply.”

The art establishment, far from withering away, as Danto predicted, has greatly expanded: “The pluralistic art world has, it turns out, been all about the diversification of the business of art.”

“It does not matter any longer what you do.” If America has never been particularly enamored of its cultural heritage — remember L.A. dealer Irving Blum, flanked by models, posing with yachts and Rolls-Royces? — does the “affectless” quality (to use Robert Hughes’ word) of Warholian corporatism simply bedeck traditional American Babbittry and philistinism with cool, ironic 60s marketing panache? (Are Warhol’s celebrity portraits of Mick and Bianca and the Shah of Iran defensible as philosophy except via the most tenuous rationalizations? Even Warhol would have smirked.) If Warholism injected adrenaline into the business side of art, it may have also administered a near-fatal anesthetic to the aesthetic aspect, helping to create the current anything-goes climate. If everything is art, as many attest, exercising empty rhetoric based on the so-called “institutional theory of art,” and utopian wishful thinking, is anything art?

I believe that it may be time to examine with a fresh eye, in Danto’s own ecumenical spirit, the legacy of this critic, perhaps as influential and instrumental in the growth of postmodernism as Clement Greenberg was in the earlier triumph of modernism. It is evident now to everyone that art and some artists have embraced commercial values to a large extent, at the expense of visual experience. If art once represented for many of us the last arena of free thought, psychic integration and the communication of the deepest parts of our authentic selves, then why have we, in exchange for a dubious freedom (from what? to do what?), abandoned our birthright, and become mayfly anti-artists? Given the intensely subjective nature of art-making, there can be no single answer. Cynical, frivolous self-indulgence, however, unmoored from reality, and adorned with theoretical bafflegab, is no royal road to self-expression; it’s a diversion and a dead end. It’s time for critical thinking — and self-criticism. Where do we come from? What are we? Where are we going?