Continuing through January 5, 2014

When she was entering Israel in 2012 for her second lecture tour and residency, Berkeley artist Christa Assad was detained for interrogation for five hours at Israeli customs. This was regrettable considering she is a third-generation Syrian-American from a Christian family. Her art, building on pottery conventions, was commenting on Middle East conflicts, and subsequently encouraged by her hosts at the Association of Israel’s Decorative Arts/Watershed Center for the Ceramic Arts in Givat-Haviva. Nearly two years later, she has attained another high point in the current body of work comprising "Proceed with Caution."

Possibly distantly related to the embattled Syrian leader, Bashir Al-Assad, Christa Assad nevertheless is criticizing suffering and violence incurred by the Syrian government, although she hastened to point out to me in an interview that the rebels have also destroyed Christian churches and, in at least one case, beheaded a priest. All this comes across vividly in the new work, a mixture of sculptural shapes such as traffic caution cones, cinder block shapes, gas masks, helmets, machine guns and hand grenades, all executed in exquisite glazed and unglazed porcelain and stoneware with painted-on scenes of urban military disasters; helicopters; crouching snipers and grenade throwers, among other images. Black and white against the creamy clay, the images are sourced from news photos, then altered or expanded by Assad. One cannot tell which side the fighters are on, which constitutes part of their appeal to the Israelis.

Like a number of other American ceramic sculptors, Assad arduously toed the line of conventional functional pottery for a decade or more before her current arrival at sculpture. With studies at conventional ceramic departments such as Penn State (BA, 1992) and Indiana University (MFA, 2000), Assad also spent years at Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, University of Leeds (UK) and at the West Virginia University program in Jingdezhen, China, the birthplace of blue-and-white porcelain. In the process, she gained amazing technical expertise to create her disturbing artworks. Until now, she has been exclusively exhibited within the ceramic world ghetto of peer-curated university group shows, national professors’ convention pop-up shows, and conservative function-oriented publications.

Amusingly, the traffic caution cones echo the wrap-around decoration of vases and pots, but with stark scenes of rebels and soldiers fighting, especially in “Deadly Dance,” “Chemical Caution,” and “Denial” (all works are 2013). Cylindrical paint-cans and poison-gas containers double as vases to decorate. “Three Gas and Tears,” “Warscape,” and “RPG ABC” are unusually powerful. “Sniper” has a full tableau of a male figure wearing a gas mask holding a machine gun. “RPG ABC” refers to rocket propelled grenade, a weapon of choice among rebels in Syria, Lebanon and Gaza. The scenes are abbreviated and schematized in some cases, all the easier to make urgent shorthand references to cataclysms and conflicts.

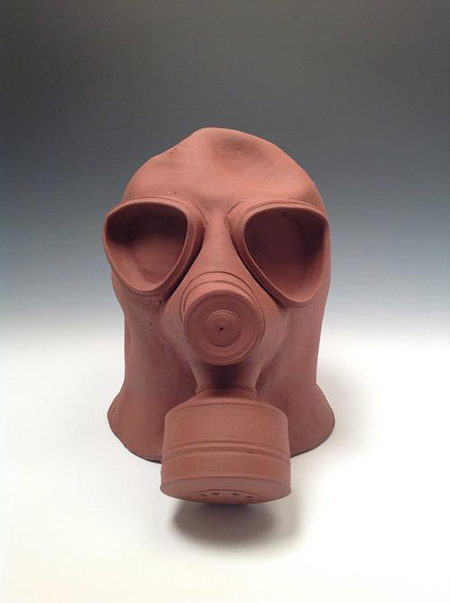

The cinderblocks, hand grenades and gas masks are more sculptural. Using the shape of a makeshift building element or destroyed building fragment, the concrete cinderblock, Assad cleverly turns it into a building surrogate, using the ends and sides as hiding places for shooters or people fleeing violence. Blacks modulate into soft grays; whites are dirty and dusty. “Large Grenade: Antique White” is nearly two feet high, a cartoon grenade, while others, such as “Bright Gold” and “Gunmetal” are six inches high. A few, like “Baseball Grenade Teapot” and “Grenade Teapot” are aesthetically derived from her earlier functional work. At the same time, all the shapes in her sculptural show are, on another level, images of useful objects as well.

Scariest of all, the gas masks are drawn from a variety of historic examples, a strategy that lifts them out of a topical, easily dated, realm, a key pitfall of political art. World War II, the Korean War, Germany, and the Russian materiel found in Syria all stand in as models and are sometimes left unglazed so that the rich fired earthenware or porcelain gleams through. “Animal Instinct” has a bloody war scene on its back side. The giant eye openings, flattened snouts and filters give each work, averaging six to nine inches high, an eerie appearance that, given recent events in Syria, is timelier than ever. Assad’s art will outlast Assad, the dictator, to be sure, because her references are ambiguous enough, sadly persistent in this century, and bound to be considered models for younger artists as how to make socially conscious art that at its best transcends the narrow and unfortunately forgettable headlines of current events.