Continuing through February 15, 2014

David Adey painstakingly creates works that involve elaborate and self-imposed criteria that govern his studio process. The results of such restraints are detailed and highly elaborate objects that address aspects of the human condition and psyche. Playful and a bit bizarre, the aesthetic is surprisingly refreshing despite the unusual bits of media he utilizes. Whether it’s discarded coffee cups, cold war technology, or fashion ads, his message is consistent and continues to get stronger. The message is about our ambivalent relationship to technology.

Adey made a strong impression three years ago at the Orange County Museum of Art's 2010 California Biennial (now the California-Pacific Triennial) with two pieces entitled "Pump" (2007-10) and "Flock" (2010). A Dr. Frankenstein-like contraption, "Pump" used a horse respirator to breath life into a football punctured with hundreds of screws. The football slowly deflated in the piece, bringing the screws closer together as it tightened momentarily before the life support system rejuvenated it again, returning the inoperative football to its ideal state. "Flock" differed aesthetically but was no less intriguing. Forty miniature ceramic lambs complete with neon halos were powered by an elaborate wiring system on a portable dolly. Much like rubber umbilical cords for power, the wiring system was bulky and reminiscent of technology carts to be seen in public schools around the country. In both works, a lifeline of support is obvious, but a systematic mad scientist ideology is utilized.

In this new series we see a continuation of these artful contrivances, but the themes are magnified. A carryover is noticeable in "Fill My Cup." A small communion cup is the base of a sculpture that rises from the ground like a reverse pyramid. Composed of found containers, the cup that is intended to hold sacramental wine instead has another cup placed within it that is just a bit larger. This pattern continues with disposable drinking cups from Starbucks, a Ben & Jerry’s ice cream container and a KFC bucket. It ironically ends with a trashcan on top. Supported by a three-tiered scaffolding system, the compulsive and fixated process seems to point toward the need for more, bigger, and perhaps better stuff. Yet the emptiness and support necessary for such a tower of need and greed is humorous.

The majority of images here are collage-based pieces composed of digital prints that are meticulously cut out and pinned to foam panels. Last year's "Gravitational Radius" is one of the earliest examples of this direction. From a distance, the sunburst image is concentrated in the center with various hues and tones of yellow and brown. Made up of hundreds of small shapes that are clustered towards the middle, they slowly break up as they reach the edges of the circle. Upon close inspection of the shapes, we learn that they are images of bits of flesh that clipped from celebrity magazines. A host of arms, legs, hands, and assorted fleshiness gradually change color as they stretch outward. Much like a completed puzzle, each one seems to be in the right place, with all fitting together perfectly. Carefully pinned to the foam board like preserved insects in a museum of science, or even a bizarre cabinet of curiosities, the shapes have the quasi-scientific aesthetic mixed with evidence of Adey’s neurotic processes. The work is a gross and overwhelming collection of a pop culture fetish. Its message is all the more alarming in that these images are deconstructed both physically and conceptually from their original state. The very real models become less obvious to the eye when nothing but their skin is featured. By combining hundreds of these body parts, they disconcertingly become one piece of fleshy tissue that is being pulled inward by a mysterious force.

Adey continues this idea with his own body in "Hide." Starting with a complete three-dimensional scan of his entire body, he unfolds this organic form using a patterning system so it can lay flat on a two-dimensional surface. The result is an irregular shape that is made up of hundreds of small triangles that connect and look like the most complex origami instructions ever composed. Picking apart the most defining physical attribute of our humanness, the grid of triangles is strange to comprehend, yet it displays that there is a pattern with a very complex geometric design to the human form. Much like fractals, it’s a mathematical infrastructure that removes the recognizable aspects of his body.

The concept of constraint is essential to understanding Adey’s work. Each piece has a particular set of rules that govern the choices he makes. The gut reactions that many artists make within the artistic process are not acceptable. If a change is necessary, Adey will return to the original guidelines and adjust the parameters that allow for different decisions, but those new guidelines must then be enforced throughout. In the limitations of Adey’s work we find the meaning and perhaps the most defining aspect of the subjects studied.

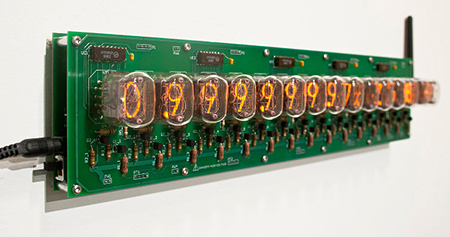

The most extreme example of Adey’s constraints is "Omega Man (Trillion-Second-Countdown) #1." Utilizing Russian-surplus nixie tubes, which basically is a fancy way of saying old electronic counters, he stages a countdown from 1 trillion seconds to zero. Built with a backup battery and linked to satellites, they will not misfire or lose count, even if powered down. Counting down before our eyes, Adey was able to enforce his restrictions on a work of art that will complete its action in about 31,000 years. Adey has the wit to engage our attention and the imaginative depth to hold it. Just be sure to check back every few thousand years.