In writing to Yinka Shonibare, MBE to gain his support for the first exhibition of his work in the Western United States, Julie Joyce, Curator of Contemporary Art at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art, likened the colonial history of Santa Barbara to “geological layers.” Recalling childhood visits to the Mission Santa Barbara, Joyce describes appreciating the stunning vista that open up around this, the “Queen of the Missions,” but recognizing also the overtly strategic importance of the location. Joyce insists, “It was not just a place of spiritual reverence and retreat; it was a military outpost. From the Mission you can see exactly which ships are coming in and out of the bay. Santa Barbara reveals its colonial history on many different levels. Some of these layers also cover it up, if you think of the architecture or the Old Spanish Days festival.”

Shonibare’s work also deals with revealing and concealing or, one might say, constructing and deconstructing power relations of the colonial period in the present day. This circular structure is reflected by Shonibare’s use of wax print fabrics, commonly identified today as African batiks. In fact, Joyce explains, the original process was invented in Indonesia. The Dutch and British decided to industrialize the process with the goal of selling the machine-made products back to Asia. The Asian markets, however, proved to be unimpressed by the new mass-produced fabrics. Joyce concludes, “The trading ships would dock in Ghana and because the batiks were still very exotic to the African royalty in the beginning, the fabric became quite popular.” Adding a final twist to the already convoluted history, Joyce points out that there is also some relation to the slave trade since the fabrics were being shipped from Europe to Africa on routes that were originally established by slave ships.

Now the fabrics are produced in West Africa and sold around the world in communities of the African Diaspora, from Brixton to the Bronx. Joyce says, “The fabric plays a big part in Shonibare’s questioning of social constructs and stereotypes. When he adopted the subject matter of the Victorian era he was just starting out as an artist and looking at these fabrics and listening to Margaret Thatcher in the 1980s proselytize the ‘return to Victorian values.’ In the United States we might not have picked up on this, but in the UK it was quite ironic. In public the Victorian era may have seemed chaste and virtuous, but in private, as we know, it was quite corrupt, to say the least.”

The new exhibition at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art, which runs March 14 − June 21, 2009, provides an ample overview of Shonibare’s work. Called “A Flying Machine for Every Man, Woman and Child and Other Astonishing Works,” it includes eight different projects comprised of more than a dozen different figures outfitted in Shonibare’s signature Victorian costumes made from Dutch wax print fabrics. The most recent work, A Flying Machine for Every Man, Woman and Child, was made in 2008 for the Miami Art Museum. The installation assembles a stereotypical nuclear family of four clad in wax print costumes, each astride a unicycle attached to an overhead propeller. Headless and of indeterminate race, as all of Shonibare’s mannequins are, these four were created as a comment on migration and immigration. Shonibare, who was born in England and moved to Nigeria at age three, is well aware of the play between insider and outsider status. Deciding to accept the title of MBE (Member of the British Empire) that was bestowed upon him by the crown, Shonibare is able to question the meaning of national identity from within.

In a 2003 interview with Anthony Downey for BOMB magazine, Shonibare said, “As an artist, I won’t take a moral position; I think it’s important not to work for any one side politically.” Instead, he explains, his aim is to put into action a series of questions or options for the audience to consider. Even the varying attitudes of the Flying Machine family present these different options: the stately, shoulders-back posture of the father figure contrasts significantly with the imbalance of the mother who attempts to wrest the machine back under control as her feet have slipped from the pedals. Joyce describes her interest in bringing Shonibare’s work to Southern California as highly motivated by these kinds of questions. She says, “Miami faces some of the same issues with immigration that we do and they’re very serious issues. Shonibare’s work speaks to that not only in terms of referencing colonialism, which dealt with economic and geographic expansion but also migration and slavery. Immigration touches on these issues in big ways. I feel that makes [Flying Machine] particularly relevant to Southern California.”

Also on view is Shonibare’s looping video work Un Ballo in Maschera (A Masked Ball). Here the exquisite costumes come to life in a dance that stages and repeats the 1792 assassination of Sweden’s King Gustav III. The unpopular King, both a victim and a perpetrator of cultural domination, was a Francophile who was especially fond of the theater and masked balls. While he overextended the country’s military in battles of conquest with his neighbors and led a decadent courtly life worthy of the French crown, Gustav III horribly neglected his own people. Angered by the King’s opulence and disregard for his domestic duties, an assassination was orchestrated and Gustav III was killed amid the confused revelry of a masked ball. Also citing a Verdi opera based on the event, Shonibare’s Un Ballo in Maschera adds yet another layer of reflexivity to the already highly theatrical situation. Shonibare’s actors proceed in silence, accompanied only by the whooshing of their thick wax print gowns and their labored breathing, waltzing forward and back. Reminiscent of the famous 90-minute long take of Russian director Alexander Sokurov’s Russian Ark filmed in the Hermitage Museum, Shonibare’s Un Ballo in Maschera seems to proceed uninterrupted, staging and restaging the historical event ad infinitum.

The Santa Barbara show reflects the diversity of media in which Shonibare works, including a photograph and a large sculptural vitrine from the La Méduse (2008) series, as well as the costumed installations and video. Joyce says, “Knowing that this would be his first Western US presentation, I thought it was very important to contextualize the work.” The La Méduse group also speaks to the Museum’s generalist holdings, which are particularly strong in the areas of 18th- and 19th-Century French and British paintings and drawings. Shonibare’s La Méduse reinterprets Géricault’s Le Radeau de la Méduse (The Raft of the Medusa) from 1818−19, which depicts the aftermath of the wreck of the French ship La Méduse off the coast of West Africa. Shonibare’s Méduse flies tattered batik sails and the small model raft is violently rocked by white-capped waves. Frozen in the approximately six-foot vitrine, history seems even more perilously trapped in time than in Géricault’s famous painting.

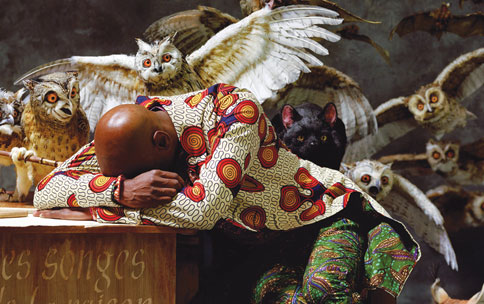

Shonibare’s 2008 color photograph, The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters (Asia), embodies many of the questions that are raised by other works in this show. Part of a group depicting each of the five continents based on Goya’s 1799 series Los Caprichos, this photograph shows a man (a self portrait in the Goya original) with his head down on a desk, his face shielded by his arm. Dressed in Victorian costume made from cotton batik, the dark-skinned man is surrounded by wide-eyed nocturnal creatures. Each image in the five-photograph series represents a man of a different ethnicity seated at the desk. Though only one of the five is on view at Santa Barbara, viewers here are often led to question the man’s identity. As Joyce explains, “The people he chose to represent the five those continents. In particular, Asia is obviously someone of African descent.” She stops, reconsiders, then adds, “Or, maybe not so obviously.” As Joyce’s own second-guessing makes clear, in Yinka Shonibare’s work nothing can be taken for granted. Identities, social groups, and power relations are methodically taken apart and reassembled in new ways that constantly force viewers to reevaluate their own role in viewing and attributing meaning to Shonibare’s characters.

This article was written for and published in art ltd. magazine ![]()