Continuing through May 18, 2014

The French Revolution’s “Declaration of the Rights of Man” did little to improve quality of life issues for women. Men retained numerous powers over “the weaker sex,” including complete control of community property and the right to have their wives jailed for the crime of adultery. Activist and playwright Olympe de Gourges, author of the “Declaration of the Rights of Women,” challenged the practice of male authority to no avail. It would not be until 1945 that women in France won the right to vote. Seeking solace from stress and frustration wherever they could find it, an inordinate number of frustrated nineteenth century Parisian women of means joined “tea parties," injecting morphine behind locked doors after tea was served and the servants were sent out of the room.

A quote from the novel “Madame Bovary” by Gustave Flaubert, “She wanted to die, but she also wanted to live in Paris,” sets the tone for the intriguing exhibition, “Tea and Morphine: Women in Paris, 1880 to 1914.” Approximately one hundred prints, books and bits of ephemera collected from this period of social and artistic upheaval represent the extremes of joy and sorrow in the lives of angelic and debased, wealthy and destitute women. They are variously portrayed by scores of male artists and one American woman living in Paris, Mary Cassatt.

Edgar Degas’ engaging print, “Mary Cassatt in the Louvre,” depicts the artist viewing antiquities. But it was Cassatt’s visit to the immensely influential 1890 exhibition of Japanese woodblock prints in Paris that would lead her towards an increased interest in color and form as she adapted the ukiyo-e (the floating world) theme of women’s everyday lives into scenes depicting the modern French woman.

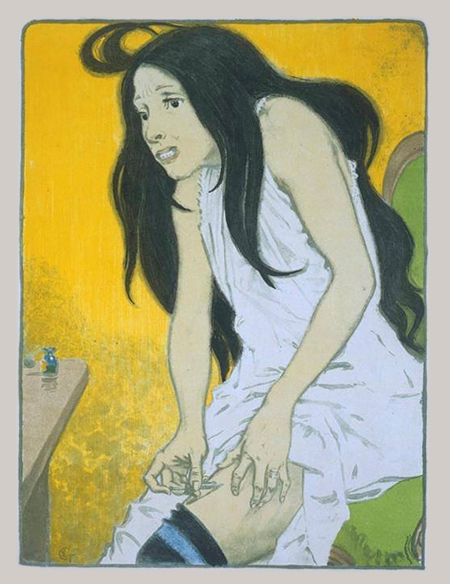

Cassatt’s delicate drypoint, “Tea,” is worlds away in style and subject matter from Eugene Samuel Grasset’s stark color lithograph, “La Morphinomane,” a shocking depiction of a disheveled, scantly clothed woman plunging a needle into her thigh. Morphine addiction and prostitution ran rampant in fin de siècle Paris, where poorly educated women had few means of support.

Paul Albert Besnard enumerates expectations for Parisian women in a suite of 12 etchings. Titles range from “Le Flirt” and “L’Amour” through “La Prostitution” and “Le Suicide.” Auguste Louis Lepére’s “Blanchisseuses, Jeunesse passe vite vertu!” addresses the backbreaking toil that laboring as a laundress took on young women. Herman Paul’s color lithograph “Rayons de Chaures” illustrates the divide between wealthy customers and the servile, poorly paid shop girls who attended them. Less physically tiring than the work done by laundresses, clerking remained one of the few positions open to women other than prostitution.

French women were “protected” from politics and other worldly concerns by a legal system based on Roman law and championed by the Catholic Church. Though they had come under attack during the Revolution, Church architectural icons such as Notre Dame remained standing with a significant majority of the population declaring themselves to be Catholic. Artists like Maurice Denis, a leader of the Nabis and prophet of beautiful icons, supported the Marian fetish with lithographs such as “Madeleine” and “La Dame Inexorable.” Henri Jean Guillaume Martin’s color lithograph “Woman Crowned with Thorns” announces its religious undertones right in the title. The caring mother in Pierre Bonnard’s “Scene de Famile” typifies imagery in a room dedicated to the depiction of self-sacrificing women who would meet with the Church’s approval. The space functions like a side chapel, protected from the likes of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec’s “La Debauche.”

But the Church began to find it difficult to retain its power in an increasingly secularized and industrialized society. Scientific studies, including Jean-Martin Charcot’s psychological theories of hysteria, were disseminated in the 1880’s, offering an image of the femme nouvelle as startling as that of Eugene Grasset’s acid thrower. Extremes in the lives of Parisian women more than a century ago retain parallels in today’s society, heightening the relevancy and allure of this edifying exhibition.