In December 2012, the veteran art critic Irving Sandler wrote an open letter to fellow art critics in "The Brooklyn Rail;" in it, he posed fourteen questions about our curious craft/trade/passion. I have previously considered the first three questions in this space, without nursing any illusions about achieving definitive answers; but art is too important to leave to art generals who seem increasingly averse to making critical judgments — in this, the ostensible Age of Critical Thinking! Sandler’s fourth question: Has art criticism been marginalized in the art world consensus? Is it influential in terms of what readers think and do?

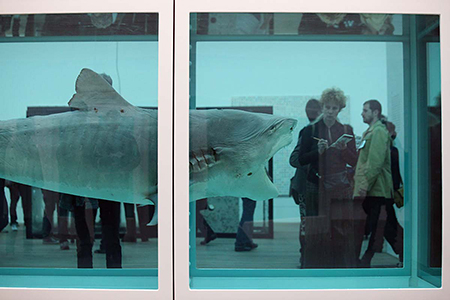

The art world’s dubious business practices have been well documented in recent years, as in Don Thompson’s "The $12 Million Stuffed Shark: The Curious Economics of Contemporary Art." (The selachian Hirst metaphor is apt, of course.) In this feeding frenzy, or Hobbesian war of all against all, art criticism aimed at the intelligent general, non-specialist reader has declined, giving way to art journalism, heavy on facts and light on analysis or perspective. Even such limited, bland coverage seems endangered, as publications count their pennies and cut what they perceive as their losses. Contemporary life, including the realm of art, has become so specialized and, with the internet, so adept at feeding a data-inundated public exactly what it wants and nothing else, that the notion of a civilized polity capable of reasonable discourse has all but vanished. So has the polity itself. Are there signs of a resurgence of the commons? Wait and see.

The decline of general-readership art criticism echoes the withdrawal of contemporary art from the intellectual commons into an echo chamber of competitive transgression. Now, the radical transgressions introduced by generations of artists during the past century to century-and-a-half made sense when kings and priests and generals ruled the world, and art was an alternative mode of thought, subversive, radical and utopian. As time has passed, however, art has become a field of competitive display, with aesthetic shock and awe goals in themselves (and readily marketable to art audiences trained in reflexive neophilia) rather than remaining engaged with reality, even at an aesthetic remove or two.

Meanwhile, the kings, priests and generals, as well as corporate bullies, continue doing as they please, undaunted by an art world that merely talks a good game, and in fact serves, to a large extent, the courtier class. Does anyone who attends art fairs today really believe that the smorgasbord of undifferentiated sensation and sensationalism serves any real purpose? Uselessness is now cited as a defining characteristic of art, and irony is pretty much mandatory, as it is in the general culture, dominated by ‘hip’ advertising. If art criticism is marginalized, it may be because art itself is marginalized to the production and consumption for elites, by upwardly striving bourgeois bohemians, of amusing, entertaining tchotchkes.

Is art criticism influential in terms of what readers think and do? Sandler undoubtedly means criticism that critiques, and does not just provide ad copy for the trade. Art criticism (or journalism — and it should be noted that that even mighty Clement Greenberg preferred the term of ‘art writer’ to ‘art critic’) is in danger of sinking into arcane jargon or giddy puffery, depending on the venue’s intended audience.

Can art and art criticism reach out to a wider audience, and aim for meaning rather than meaninglessness? In the opinion of this art lover, they must, or become irrelevant and decadent. Ronald Reagan used to say that he left the Democratic Party because the party left him. Whatever the truth of that statement (and I question his populist sentiments), it does provide an analogy for contemporary art’s desertion of reality in favor of William Butler Yeats’s“ circus animals ... all on show.”

“Players and painted stage took all my love,

And not those things that they were emblems of.”