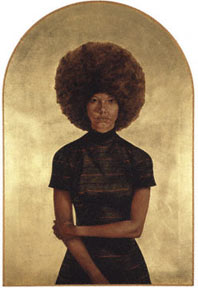

Barkley L. Hendricks, "Lawdy Mama," 1969, oil on canvas, 53 3/4 x 36 1/4'.

During the 1960's and '70s the line between high and low culture, popular and privileged art was cast into doubt. This gave rise to the postmodern deployment of hybrid strategies that integrated the most visually and intellectually dynamic elements of both. If the emergence of Pop art most familiarly denotes this historical shift, artists contributed to what became a sea change in a variety of ways that sometimes were not apparent until decades later. Barkley L. Hendricks has worked and taught in the academic environment of Connecticut College for over 35 years, quietly establishing a legacy that may set him into this larger historical narrative in some specific and distinctive ways.

Hendricks' work in this show, “The Birth of the Cool,” represents postmodernism at its trickster best. One has to work to detect the paintings' historical and/or art historical references, as well as their sometimes couched semiotics that comprise a socio-political commentary. Barkley, who is African American, presents mostly realist portraits of black people he has known or observed while growing up in North Philadelphia during the late 1940's and 50's. Not coincidentally, Miles Davis' recorded his landmark Capital Records album titled “The Birth of Cool” in 1949 and 1950. This was a seminal work that moved jazz beyond be-bop, and Barkley's art shares with Davis' music a similar sophisticated smoothness, stylish elegance, surface allure, pristine playfulness and introspective thoughtfulness and sensitivity.

For example, in “Lawdy Mama” (1969) a woman with a large Afro hairdo stands against a matted gold background. As readily as the image might refer to a photograph snapped in a dime store photo booth, the arch-shaped gold leafed canvas references a late medieval altar panel. The woman is elevated into a modern day saint or madonna.

The artist addresses race and racism throughout this survey, not in a self-righteous or preachy manner, but with inventiveness, subtly and via an accessible and colloquial inner city visual vocabulary, that from another point of view also comes to stand as historical 'documents' of the era in which they were made. “What's Going On?” (1974) composes an ensemble of hip and trim young men adorned in ‘70s-style creamy white leisure suits, each one gazing askance in different directions. But lo and behold, the artist has also slipped in an identically clad female incognito among the men, while another woman standing among them is nude and very dark skinned. Naturally she jumps out as the most conspicuous member of this group. Even so, this second woman goes unnoticed by the others. If this alludes to the importance for all people to feel comfortable and natural in their own skin, it also throws a brick at the cliché of the hyper-sexualized black man and woman. The title borrows from Marvin Gaye's classic album that addresses the problems seen in America from the point of view of a newly returned Vietnam War veteran. In the absence of self-consciousness among the members of this ensemble, the painting suggests (with another nod to 1960's/'70's thematic values) that we are all to one another brothers and sisters, not predators and prey.

Consider as well “Tuff Tony” (1978), a portrait of a black teenager wearing a t-shirt with the initials of a high school, ‘MCHS,’ printed on it, as well as the word 'swimming' appearing beneath them. That Hendricks also deserves recognition as a conceptualist, rather than strictly a portrait painter becomes clear by virtue of the fact that people don't often associate young black men (or women, for that matter) as champion swimmers, and this strategy, again, throws viewers' perhaps overly relaxed reading of the image into question.

Indeed, there is an heroic energy, vivid imagination and intellectual vigor at work throughout this show that strives to restore, quite literally to sight, the divine uniqueness of each of Barkley's subjects. If chronic racism indeed made contemporary America, in the recent words of Attorney General, Eric Holder, “a nation of cowards,” then Barkley's art serves both as this statement's salvo and its antidote. For it is impossible for anyone not to see themselves in the faces of spirit and joy, intelligence, hope and pain with which Barkley has graced his subjects in these paintings with such apparent generosity and ease.

Published courtesy of ArtScene