Continuing through June 29, 2014

Speech that touches upon descriptions of the divine frequently employs the imagery of light. Without cataloging a litany of examples from Christianity and Judaism, not to mention Hinduism and Buddhism, it is hardly surprising that this is equally true with regard to Islam. In fact, one of the names of the Koran is an-Nur, the Light. Thus, the following text from the Koran proves, well, illuminating:

"God is the light of the heavens and the earth. The parable of His light is, as it were, that of a niche containing a lamp; the lamp is enclosed in a glass and the glass shines like a radiant star; the lamp is lit from a blessed tree — an olive tree that is neither of the east or the west — the oil whereof is so bright that it would well-nigh give light of itself even though fire had not touched it: light upon light."

This single bit of metaphorical text recalibrates our notion of "Nur: Light in Art and Science from the Islamic World." The text, of course, is a description of mystical illumination. It describes a light that confers brightness despite its lack of a literal “oneness” with the source of fire that is “not touched.” If you look for similar explanatory materials relating to the show at the museum you will be disappointed. This is particularly lamentable since most Americans only know the Muslim faith via its relationship to the events of 9/11. “Nur,” then, should not be overlooked; that would be a missed opportunity since the show can teach us much. That being said: For a show celebrating light and its concomitant ramifications, it is daunting that museum goers are forced through what feels like a fluorescent tube to enter the exhibition. It’s not the gorgeous light of North Africa or Spain; it, instead, is offensively tacky and reminiscent of a buying spree at Home Depot. However, if one is willing to endure this less than august entrance and engage in a bit of investigation regarding one of the three Abrahamic religions, this exhibition delivers treasures that, despite a flagging presentation and lack of information, can still delight.

In fact, the Sufis — adherents to Islam who many scholars feel offer a merging of heart and intellect with regard to the divine that outstrips any equivalent in the West — turn to symbolism and imagery to apprehend the divine. Thus, a show of Islamic art is of tremendous import. And the DMA has put forth a collection about which they have crowed mightily. They have counted pieces, measured them, and described materials and points of origin with alacrity. But will those who view the show leave with an expanded understanding of a faith that is often met with furor or even violent repugnance? The resounding answer is “yes” — if they are willing to look, read, and reflect.

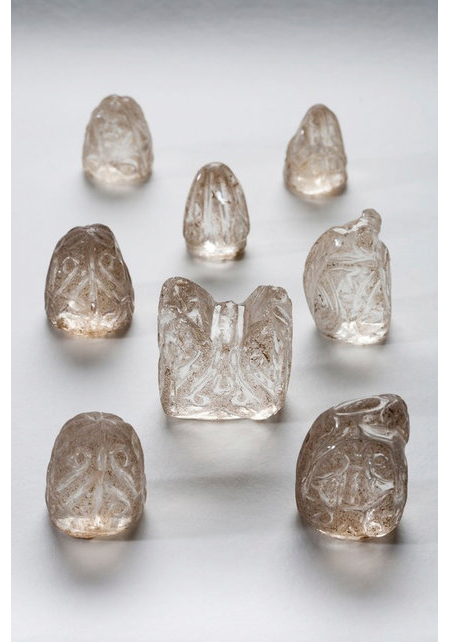

For instance, the show displays astrolabes, images of the zodiac, medical arcana, calligraphy, bowls, urns, and miniature paintings. However, these items, bereft of contextual information, do little more than deliver a glancing blow when it comes to understanding the expanse of Arabic learning. As one example, Muslim scholars either saved the surviving Greek canon from destruction or, at the very least, offered commentaries on it that made Aristotle and other notable scholars far more accessible to the West than would have otherwise been possible. This is a mere aside, yet it provides valuable context that would have enhanced the public’s ability to appreciate and apprehend it.

However, go and experience the artifacts on display. Don’t count them or care over much about their size or point of origin. It is far more important that you’re in the presence of objects that intimate a large, brightly lit world. And dare we say it? A transcendent one. In his work, Mishkat al-Anwar, al Ghazzali interprets the Sura of Light quoted in the second paragraph of this review. He explains that the Creator alone exists or has being. Everything else “has being not in itself but in regard to the face of its Maker, so that the only thing which truly is is God’s Face.”

The corollary within the context of the show is that everything comes to us as a redacted version of a divinity most aptly described as an iteration of light. After all, both confer the glint of beauty and a means by which everything that is can be oriented in the world. To understand this notion — or, more precisely, to inhabit this mindset — requires a new way of seeing. The DMA has delivered to the public some glorious objects to scrutinize. So why are they so terse when it comes to celebrating them? They tout the size of the show with vengeance but fail to give us compelling reasons for loving it. After all, most of us can count. So sheer numbers don’t really offer a new vector into what is an otherwise, for most, an opaque culture. There are 150 pieces in “Nur." The Louvre owns about 14,000 artifacts housed in their Islamic wing. Airfare, hotels and left bank dining are expensive — and “Nur: Light” is close at hand. So give yourself over to it in ways that are deep and thoughtful — in lieu of merely mimicking awe regarding its “staggering” scope.

Learning about Islamic culture may be daunting to many people outside the Muslim community. However, what is a demanding task for some is an electrifying gallop for others. In either case, allow yourself to enter into another culture and you won’t become lost. Rather, you’ll come to know your own tradition better.