Irving Sandler’s fourteen questions to fellow art critics and writers, published in Brooklyn Rail in late 2012, have proven to be stimulating reflections on various aspects of art and art writing. I have been tackling them in this space from time to time. Question Six: How would you define yourself as a critic? Reviewer? Essayist? Theorist? Artist-critic? Blogger?

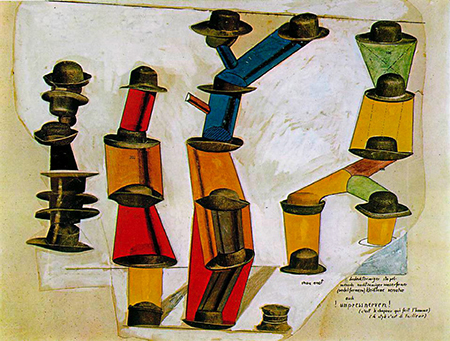

Almost everyone in the art world wears more than one of these hats, of course. Most artists have more than one job for their entire careers — unless they’re successful at transforming their creative work into a paying job, or business, a consummation devoutly to be wished, one would think, but one with a couple of considerable drawbacks: is making and flogging your very own brand of aesthetic widgets creatively and emotionally satisfying? Succeeding in the art business without really trying is just about impossible, but isn’t maintaining market share in aesthetic widgets a kind of slavery unworthy of free, creative people? Cue up Robert Morse and Sammy Smith singing “The Company Way,” from How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying.

Staying true to the ideal of self-realization while surviving economically dictates a lot of compromises in the uncertain and constantly-shifting art world. Most art critics are not paid a living wage — five dollars a review in Clement Greenberg’s day! — and teach or do other art-related work. I began writing reviews of Bay Area art exhibits in 2000 as a way of indulging my passion for art while withdrawing from art practice (at least temporarily, in a strategic retreat). Art writing allowed me to support and encourage artists of merit who were ignored or under-recognized, and to try to influence art discourse that had become too arcane and issue-oriented, and not focused enough on craftsmanship, how objects looked and how they transmitted emotion and personality. Art had too frequently become propaganda for certain political positions, but with a winking eye toward the market commodification it professed to despise. While supporting both political art and art as a collectible object, the de-aestheticization of art promulgated during the Theory Era seemed completely wrong-headed, and in time this has come to be clear. David Levine’s and Alix Rule’s canopycanopycanopy.com article on International Art English and John Seed’s huffingtonpost.com parody of the academic artist statement are by now well-known, or should be. There are a number of Artist Statement generators online as well; artist bots writing for, apparently, collector bots.

Returning to Sandler’s question, and the hat metaphor, I’d answer that I am primarily a reviewer, which is for me a cross between journalist and critic. ‘Journalist’ implies a generalist focus; ‘critic’ connotes a fixed aesthetic standard against which artworks are measured. Both of these approaches are valid if not carried to the extremes of, respectively, ‘fun’ populism and art snobbery.

All artworks have underlying ideas and theories, but their fashionableness or even factual truth are not and should not be the sole criteria by which we judge art. One of my English teachers in high school said — shockingly, at the time — that we do not judge great literature; it judges us. If we cannot see, say, the Sistine Chapel, which Willem DeKooning called “just about the greatest thing ever done,” because of the sins of the papacy or the postmodernist disbelief in human reason (among the tenured classes, no less!), then maybe we get the bad art we deserve. Repeal Gresham’s Law in art. Let’s take art seriously again and keep it real and vital.