Continuing through October 19, 2014

The art in “Deco Japan: Shaping Art and Culture 1925-1945” is not completely unfamiliar to Seattle residents. Kagedo Japanese Art has sold examples for years, long before it became fashionable to show the hitherto unfashionable objects of the contested interwar period. And one collector, the late Howard Kottler, artist and ceramics professor at the University of Washington, amassed a huge collection of Noritake porcelains of the period that are better than any Robert and Mary Levinson, the sole owners of the current exhibit, ever acquired in their travels, a few of which are on view here.

Of all the national venues — New York, Albuquerque, and Palm Beach — none is so appropriate a container for “Deco Japan” as Bebb & Gould’s art moderne building in Volunteer Park. It debuted in 1932 as the original Seattle Art Museum, and was almost exclusively dedicated to Asian art at the time. In fact, an exquisite silver cigarette box with a linear, splashing fountain design is brilliantly echoed in the museum’s pair of fountains that grace the north and south ends of the severe, yet curved, façade. Newly restored, they were fully operating the day I visited.

After the 1925 Paris “exposition des arts decoratifs” (hence the nickname “art deco”), the geometric, elegant style spread throughout the world. Japanese artists were already in on the ground floor; several even served as jurors for the extravaganza. Japanese expatriate artists returned home full of new ideas and proud that Japan was not only an acknowledged influence on the new style in Paris — lacquer, repeated textile patterns, metalwork and subject matter drew on Japanese sources — but was open to non-Japanese influences that soon became hallmarks of nascent Japanese deco. Egypt, China, Europe, Latin America and the U.S. pop up as sources in this provocative exhibition.

Why has it taken so long to chronicle and appraise Deco Japan? Because, until recently, the era was tainted politically, called by one historian a “dark valley of cultured decadence and militant nationalism.” This is a shame because, not only are the 200 paintings, prints, photographs, sculptures, clothing, and household objects bright and beautiful to contemplate, they bear none of the tacky political imagery of German and Italian deco from the 1930s.

In Japan, a kind of glamorous department-store fascism propelled the success of the movement as more and more middle-class Japanese could afford the cachet of completely superfluous, high-end knickknacks. The lovely bronze, silver, lacquer and cloisonné representations of a fighting rooster, flying fish, dragons and the phoenix are covert symbols of military power that were instantly clear to the affluent homeowners who bought them. The virility of the cock; the aerial feats of the fish; and the powers over both earth and air of the dragon and phoenix reinforced consumer taste and shifting state mentalities, frequently demonstrated through official exhibitions, often with the addition of royal patronage. In 1927, a French architect was hired to design the Teien Palace for the imperial prince.

Divided into categories such as “over and under the sea,” “the cultural home” and “the Floating World transformed,” the intimate, polygonal galleries allow plenty of space for even the tiniest of gold-and-silver trinkets such as sparrows, butterflies, birds and beetles, along with cast-glass desk clocks, elaborate hibachi holders and numerous lidded boxes of lacquer or metals. On the latter, decorations of birds and fish gave way to bold “rising suns” that invoke the era’s imperial flag. Their version of the swastika, the rising sun was perfect for extended geometric bands on vases, screens and display stands that originally accompanied such special items.

Compared to the militarily symbolic animals, a more benign imagery of lobsters, peacocks, tortoises and even parakeets suggests the happier, less anxious times of the 1920s. Besides the splashing fountain parallel, there is also a bronze “Recumbent Camel” (c. 1938) that is apposite to the two Ming Dynasty life-size seated camels at the building’s entrance. Surely guardian symbols of western China’s exotic expansion into Central Asia in the 15th century, they now remind us of new problems among restless Chinese Muslims in Xinjiang, the same area. And the banana flowers on a monumental room-divider screen also suggest Japan’s military tentacles reaching to the South Pacific.

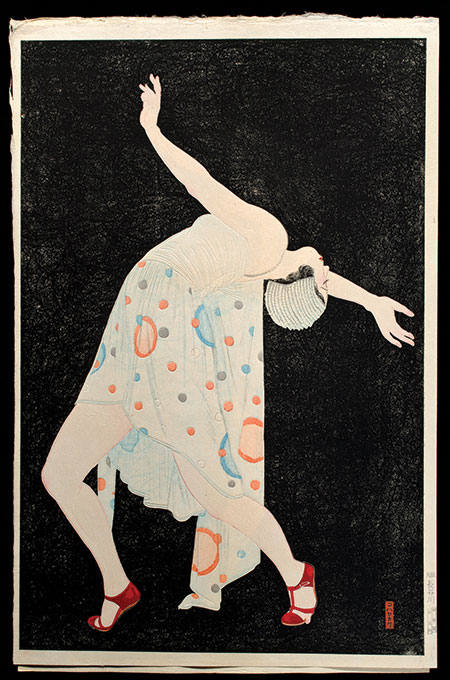

Few Asian countries experienced as rapid an embrace of foreign influences as did Japan before World War II. “Deco Japan” reflects this beautifully. Unlike SAAM’s normal exhibits of the rare antique Asian art favored by connoisseurs such as the museum’s founder, Richard E. Fuller, “Deco Japan” is aimed at average folks, anyone who likes to dance, go to a nightclub, get a short haircut, see a movie, or write a letter; exactly what Japanese people did before the cataclysm of war.