Continuing through July 3, 2014

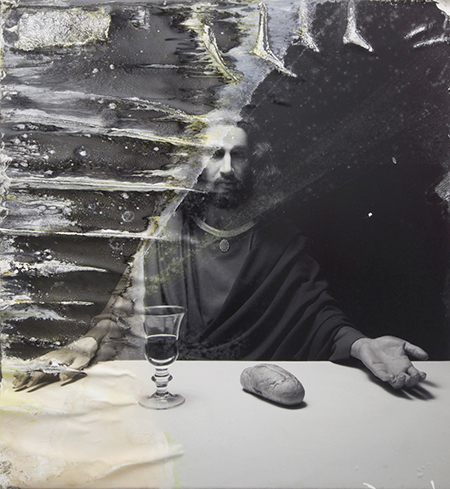

The ambiguities of artistic representation and the mysteries of time pervade Hirsohi Sugimoto’s stunning, mysterious photographs of figures from wax museums and taxidermy specimens from museum dioramas; movie theater interiors, their screens bleached by cinematic light during long exposures; and placid but enigmatic stretches of ocean. These themes recur in his current show, which takes its title from an artwork that some museum should do whatever it has to do to acquire “The Last Supper: Acts of God,” a five-panel polyptych stretching twenty-plus feet that dominates the main gallery. Depicting a Japanese waxworks version of Leonardo’s famous but decayed painting, doomed from its start by the artist’s insistence on using oil on the plaster walls of a monastery’s refectory, the work sat in Sugimoto’s basement from 1999 to 2012, when it was damaged by Hurricane Sandy flood waters, leaving streaks, stains and ripples that the artist took as completion by “the invisible hand of God.”

These marks of aging parallel, for him, the insults of time, neglect and inept repair visited upon the original, in Milan — perhaps the most graceful philosophical-aesthetic embrace of accident since Duchamp (the modernist’s Leonardo) decided that cracks in his Large Glass completed it. They also recall the real or fake antiquing damage in works by E.J. Bellocg and Joel Peter Witkin, visually distancing, but nonetheless poetic; call it the Shroud-of-Turin Effect. The figures themselves are creepy, like the relics of martyrs, but hyper-expressive.

A seascape, “Sea of Galilee, Golan,” is accompanied by wall text — for moderns who skipped Sunday school — recounting Jesus’ walk on the waters, and Peter’s foundering due to a momentary crisis of confidence; o ye of little faith! A third body of work, "In Praise of Shadows," reflects Sugimoto’s love for “the ancient past” at least in respect to artificial light. Lighting a candle by an window, where it would flicker and waver in the breeze, the photographer created these five silver-gelatin works by making long exposures for the entire “life of [each] candle.” The resulting abstract vertical white forms with ragged edges of the flames path suggest aureoles, mandorlas, pillars of fire, and other luminous symbols of the numinous.