The internet giveth; the internet taketh away. Digital communication has served as an enabler for everyone (perorate in your pajamas at all hours!), which is miraculous in a time of declining art journalism in general-interest publications. The downside of this mass empowerment is that amid the Babel of voices (some, frankly, silly and self-serving), thoughtful opinions can be an oasis in the desert. John Seed, a painter and professor of art at Mt. San Jacinto College in southern California, has been since 2010 a regular contributor to Huffington Post (johnseed.com). If HuffPo posts a fair amount of fluff, Seed is always worth reading for his thoughts on contemporary art, a subject not usually associated with seriousness or common sense or plain speech. His recent parody of contemporary artspeak as foisted on a reborn Michelangelo or Titian (Artist's Statements of the Old Masters) is a classic – a briskly funny art-world equivalent of Mark Twain's deflation of James Fenimore Cooper's stagy, prolix style. In an essay titled "James Fenimore Cooper's 'Literary Offenses," "The Deerslayer," Twain concludes, is not shapely Art so much as "literary delirium tremens."

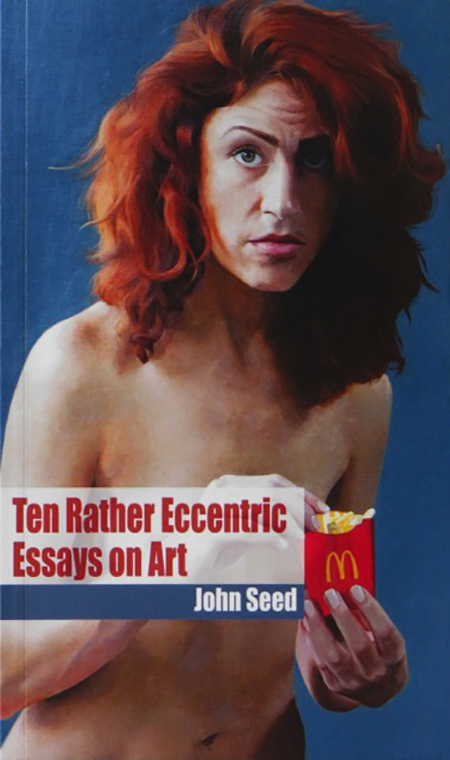

Now Seed has published a small selection of his Huffington pieces, entitled "Ten Rather Eccentric Essays on Art." It is concise and concerned about the state of art today, but far from dogmatic or theoretical, since Seed considers himself an artist rather than art historian or academician. Nevertheless, this quick 52-page read raises issues that all artists need to consider, and even modestly posits a few solutions, or at least adjustments to current practice.

Seed begins by placing eccentricity in context with a quotation from the 19th-century English philosopher John Stuart Mill: "The amount of eccentricity in a society has generally been proportional to the amount of genius, mental vigor and moral courage it contained. That so few now dare to be eccentric marks the chief danger of the time."

Mill's time was marked by a concentration of power at the top, as ours is. But, you say, surely we live in a time of unparalleled artistic creativity and eccentricity. Are we, really, or have we simply institutionalized and fetishized art that has no stake in society or the future of the planet – that actually colludes with One-Percenters, in a sense, washing them clean with the blood of cult heroes? (Before Christianity's rather tame symbolic rites, Mithraists purged away their sins by standing beneath grates holding slaughtered bulls. Yes, we art writers have to know this stuff.)

Seed argues for art's continued relevance fifty years after art cut the cord with the past and ventured into the brave new world of experimentation without limits, resulting in today's fast-food art. In "I Don't Deconstruct," Seed declares his shockingly heterodox allegiance: "… my intention is to write about works of art and artists simply because I like them. The human being behind every work of art interests me quite a bit, but the categories, schools of art and doctrines that they might be connected to really don't. I take the approach the Dalai Lama suggests, looking for what I have in common with people – and artists – before I consider how we might differ in our views.

In "When Appreciating Works of Art, Being There Is Always Best," he stresses the importance of seeing the real art object, and not just the ubiquitous stamp-sized jpegs that are both blessing and bane, citing John Dewey on the necessity of the aesthetic experience, "a product, one might almost say by-product, of continuous and cumulative interaction of an organic self with the world. There is no other foundation upon which aesthetic theory and criticism can build."

In "Toward Eclecticism," Seed champions subjective personal taste as the royal road to aesthetic discrimination. His brief, modest manifesto – "I like anything that is good." – belies the effort we all make when developing a discriminating eye (and not just a theoretical ear) and the value of an open, non-doctrinaire attitude. Seed: "Being eclectic means always being open to acknowledging that something good can appear outside of any system you have set up. Eclecticism is infinitely flexible and paradoxical …" He reiterates his predilection for the human and eccentric in "On Taste, Richard Serra and the Green Eggs and Ham Syndrome:" "Your taste is who you are. My taste and I are both human, flawed, and always evolving." In "An Alluring Woman with Fries and McDonaldization in Art," Seed interprets Nadine Robbins' painting, "Mrs. McDonald," as depicting the corporatization of contemporary life, and the co-optation of once-adversarial avant-gardism by the worlds of fashion and entertainment. "I like artists who are inefficient and whose motivations are human, fallible, and unpredictable to the point of being quixotic."

It's time for the art world to re-examine the premises that have predominated in recent years, including, in my opinion, its doctrinaire neophilia, or academicized avant-gardism, and an assumption that art is fundamentally made for the delectation and flattery of elites, a claim that Tolstoy made in his prescient 1897 "What is Art?" Seed's rather provocative book is an excellent guide for the art-perplexed, and an excellent introduction to these timely topics.