Continuing through August 23, 2014

When the figurative paintings of Eric Fischl came onto the scene in the late 1970s and gained prominence through the 1980s, he challenged the art world’s prevailing taste. He rejected convention with both irreverent content and technique. His dazzling evocations of light and shadow added to the overall tensions of scenes that were emotionally charged. It was style and content, rather than technique that propelled viewer reactions.

Always fond of exposing realities usually kept hidden, the provocative pull of his psychosexual dramas proved compelling. His lack of fear at tackling sticky subjects led to enigmatic depictions of family dysfunctions, suburban unhappiness or adolescent sexuality. Fischl always allowed the element of uncertainty to play a major role. Speculating on what was happening or about to happen created ambiguous and unsettling tensions, particularly since his unique perspectives placed spectators uncomfortably at the center of the scene. Viewers were not merely voyeurs; they felt part of the action. His current exhibit spans most of the last decade, focusing between two-dimensional work and sculptures.

Through the years Fischl has polished his technique, working in a variety of mediums and consistently striving to reach emotional cores. His explorations into the nature of light have not only taken new forms, they continue to remain critical to emotional resonance. His recent series of cast resin collages and translucent glass sculptures reveal how light behaves when it penetrates surfaces. In the collages, for example, light passes through transparent and opaque layers to illuminate figures. Fischl’s impulse to delve into the human condition remains paramount. In a series of watercolor beach scenes, he lays bare individual isolation. Forms rendered with a broad brush are dominated by arabesque rhythms and the radiant play of light on sand and water. Though figures are part of a crowd, they don’t interact. The sense of existential isolation is palpable. Fischl continues his explorations of body language through a series of bronze and glass sculptures. His sentiment that we are each solitary beings is further evidenced in “Congress of Wits,” in which five bronze figures appear to be dancing to their own individual tunes ... together, yet disconnected.

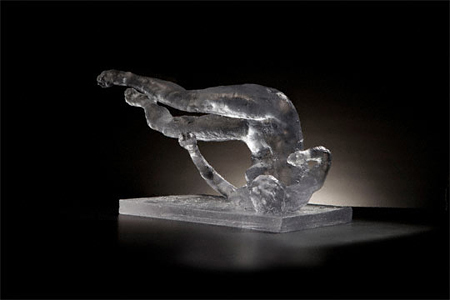

Fischl has been compared to Degas, who believed in launching a frontal attack in order to create discomfort … to be a provocateur so to speak. Indeed, he does manage to establish dynamics that destroy equilibrium. This is particularly evident in bronze and glass life sized sculptures of individual women. Like Degas’ women, they assume uncomfortable positions, such as squatting, kneeling and arching. The most provocative is the life sized glass figure, “Tumbling Woman 11.” Naked, with arms and legs flailing above her head, she is rolling on her back in a state of constant motion. Fischl’s stated attempt was to depict that “we are not in a state of equilibrium.” Controversy erupted, however, when a bronze version of that sculpture was placed in Rockerfeller Center in New York City. In spite of Fischl’s intended concept, the female figure brought to mind visions of people leaping to their deaths during the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Center. Seemingly unaware of the raw nerve he hit, Fischl was apologetic, stating that he was merely attempting to express the vulnerability of the human condition, that he had not wished to offend. It is a prime example of how artists think about and create their own realities.

Published courtesy of ArtSceneCal ©2014