Art collecting is a facet of the larger world of collecting in general. My recent research has revealed a variety of explanations and observations about the nature of collecting, some of which I would like to share with you here. From the Renaissance forward, collecting has involved a matrix of artist, collector and possibly agent or dealer. Each has a performative role to play whether maker, purveyor or consumer and each has had his or her say about a topic at once liberating and confining; fulfilling and frustrating; exhilarating and exhaustive.

Karl Marx put it succinctly when he noted that collecting "is a definite social relation between men that assumes in their eyes the fantastic form of a relation between things."

Amplifying such an idea, Roger Cardinal (who coined the term "outsider art") holds that to begin to collect "is to launch individual desire across the intertext of environment and history. Every acquisition… marks an unrepeatable conjuncture of subject, found object, place and moment."

The history of art patronage is also the history of collecting. Long before galleries existed, royal and aristocratic patrons contacted artists directly or worked through intermediaries to commission specific artworks. Sometimes this worked well; at other times such pre-conditions were rebuffed by the artist. Both Bellini and Leonardo said no to Isabella d'Este (1474-1539), but Perugino and Titian eagerly snapped up her jobs. Amusingly, Isabella had warned Perugino not to "add anything of your own invention" before he completed "The Battle Between Love and Chastity" in 1501 for her "studiolo," among the first private art museums in Europe.

So is it the collector's hope of posthumous posterity that fuels such obsessions? Or, more crudely, the hope of collecting for investment purposes? The late Bagley Wright, former Seattle Art Museum board president and interim director, assembled with his wife Virginia a collection of postwar American art valued in the hundreds of millions of dollars today. In a preface to the 1999 SAM catalogue of their collection on exhibit, he addressed French philosopher Denis Diderot's snide 1767 remarks about people collecting so their children can inherit and sell things at "twenty times the initial value."

"I'm sorry, Monsieur Diderot," Wright retorted. "Collecting is a much more complicated matter than you seem to believe. It is difficult to understand why sensible people become obsessive collectors buying paintings when they have no more wall space… I can only admit to a passion that has held us in thrall for a long time." Over the years, the Wrights were offered an escalating $8 to $80 million for "Thermometer" (1959) by Jasper Johns. It will remain in Seattle with all the other treasures they are gifting to SAM.

Delving more deeply into the psychology of the collector fascinated 20th-century art critics and art historians. Cardinal held that "the collector's taste is a mirror of self." Psychoanalyst and art historian Werner Muensterberger reminds us that collecting is "inextricably bound up with an inner need for ever new supplies for the enhancement of the self," but also warns that collecting derives from "vulnerability and a subsequent longing for substitution, closely allied with moodiness and depression."

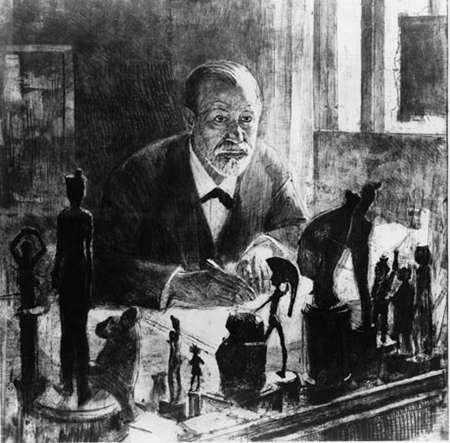

Time is another reoccurring trope in discussing the collector. As W. D. King put it, "collecting is a way of linking past, present and future" and called it "my refuge from the present, as from the past." Marilyn Karp later argued, an artwork "evokes the culture in which it was created." This does not explain contemporary art collectors' emphasis on the present, but with the passage of time, such presentness evaporates, leaving the artwork as another relic or artifact to be contemplated or, as Sigmund Freud did with his desktop collection of ancient art statuettes, fondled while eating his sandwich for lunch.

At the extreme end, Robert Opie and Russell Lynes respectively proclaimed collecting as "being mad" and "a galloping disease." As one wag put it, the difference between collecting and hoarding is money. William Randolph Hearst was never called a hoarder because the cultural value of his pillaging of entire buildings and European architectural interiors was so high, far higher than the prices he paid. The fabled Collyer brothers in New York City, however, who died in 1947 when their collections of books and newspapers collapsed onto them, acquired largely worthless things.

Only philosopher Jean Baudrillard would define collecting as absence: "The collector partakes of the sublime… by virtue of his fanaticism. An object only acquires its exceptional value by dint of being absent… what we have begun to suspect is that the collection is never really initiated to be completed."

More charitable and therapeutic, Muensterberger concludes our brief survey by pointing out that "the objects they cherish are inanimate substitutes for reassurance and care… These objects prove, both to the collector and to the world, that he or she is special and worthy of them."