Continuing through August 29, 2014

I’m inclined to regard the Yorkshire landscapes that David Hockney has been turning out for the last nine or so years as possibly the finest body of work he has done, a distillation of lessons learned over a lifetime of observation and experimentation propelled by an ambition to make the fullest possible use of the European art canon.

That ambition, it should be noted, has its pitfalls. Hockney’s talent, for better or worse, has always been that of an extraordinarily adept pasticheur. You can see this from the very beginning of his career when he’s absorbing and cute-ifying Dubuffet and Bacon and Ab Ex. Later on he adds Matisse, Bonnard, and Pop’s flatness and graphic incisiveness to the mix. The combination serves him brilliantly in fabulating a vision of Los Angeles as an all-white lotusland bedecked with blue swimming pools and young male bubble butts. (According to the Tate website, “In California, Hockney discovered, everybody had a swimming pool.” Everybody.) Later still, he latched on to cubism and mined it for decorative motifs and compositional ideas. In all this, as Mark Hudson astutely noted in a Telegraph review, “Hockney’s strength was his lightness of touch in appropriating and juxtaposing diverse graphic forms.” He was, according to Hudson, “post-modern before the fact,” which is perhaps an indirect way of stating that as an inveterate painterly magpie he anticipated what in the ‘80s would become standard artistic operating procedure.

Lightness of touch has been both Hockney’s strength and weakness, imbuing his prolific output with an often irresistible charm and vitality but also allowing it to lapse into trite industriousness. What sets him apart from every other artist associated with Pop’s cartoony idiom is the sheer range of art historical references he has been able to accommodate. This canonical fluency allied with an enthusiastic embrace of the latest reproduction technology have enabled Hockney to continue to surprise himself and his audience.

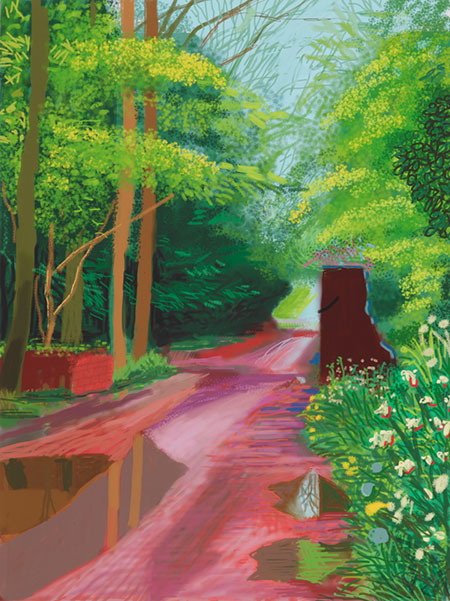

The works on display in this show, entitled “The Arrival of Spring,” were created on an iPad using a paint program called Brushes and then ink-jet printed using a process that allows pixilation-free enlargement. They include 16 images measuring 55 x 41.5 inches and four large-scale images measuring 93 x 70 inches.

Hockney’s interest in digital drawing goes quite a way back. He started on iPhones, joking that the devices were sketchpads to which he occasionally talked, then transitioned to iPads. Although diehard technophobes keep insisting that digitizers and virtual brushes can never achieve the subtleties and liveliness of physical media, Hockney’s drawings prove otherwise. If anything, the mobility of these devices, the endless layerings and erasures that their surfaces and software permit, the fine control over blending and transparency they grant, and the astonishing range of media they can simulate, open up dizzying possibilities for the draftsman who can overcome the medium’s off-putting lack of tactile feedback.

The actual subject of these drawings from 2011 is less the landscape they depict as the theatricality of drawing. Van Gogh’s careful pen drawings of tilled and tidied farmland tell us of his longing to achieve the idealized dignity of the peasants whose calloused hands constructed the landscape before the artist arrived to reconstruct it. Hockney’s invocation of Van Gogh’s stippling and hatching overlaid on passages of vaporous color, suggestive of proto-fauve Monet, argue instead the dandy’s conviction that contact with nature is but a means to find in it what art has already rendered picturesque. By now, most of us have encountered this proposition as a belabored postmodernist assertion of the omnipresence of mediation and artifice. For Hockney it is a built-in orientation that is at once the basis of his untiring productivity and its limit. Van Gogh went to the countryside seeking solidarity. Hockney goes to the countryside looking urbane.

“The Arrival of Spring” is exuberant eye candy, a section of Yorkshire countryside transformed into a series of backdrops for whatever tasteful fête galantes the potential owners of these works might care to stage in front of them. They engage by virtue of the sprightly intricacy of Hockney’s mark making, the delicacy and sophistication of his color, the virtuosity of his orchestration of textures and forms and his deft integration of lessons learned over a lifetime of formal exploration.

Published courtesy of ArtSceneCal ©2014