Continuing through August 17, 2014

When a towering sculptor, like Auguste Rodin (1840-1917) drew on paper with pen, ink, pencil, or other graphic materials, his powerful hands were continuously carving form in space as if manipulating pliant clay or obdurate stone. Sculptural form is impossible to fully capture in drawing. Yet, Rodin conveys a sense of volume, in-the-roundness, human flesh and muscle despite the medium’s flatness. For Rodin, the human body was a source of never-ending inspiration. Human anatomy was living sculpture - exquisitely designed, mobile, and changing in endless configuration, different with each person, never repetitious. Because of the freshness of rendering each figure, Rodin’s desire to work with the human form was never satiated. It was his obsession. Sculptural form not only helped him see drawing with an expanded vision, his innovative forms contributed a new vocabulary to the works of master painters of his day.

In 1897 the House of Goupil published a limited edition of 127 Rodin drawings inspired from Dante’s "Divine Comedy." The Goupil Museum in Bordeaux, France now possesses no. 38 of this edition, entitled "The Drawings of Auguste Rodin," also known as the "Feinaille Album," the name of the artist’s patron. The current exhibition also includes 29 plates after drawings executed for the unfinished masterpiece, "The Gates of Hell,” along with essays and other works on which Rodin devoted many years to rigorously perfect.

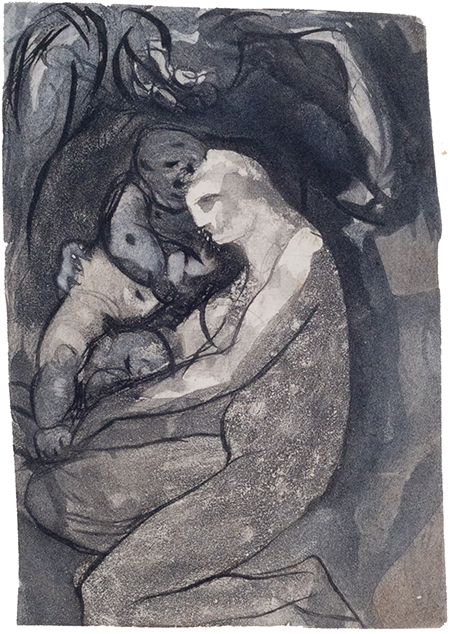

In these pen and ink drawings on display, Rodin’s passions and drive to push his work forward gave the world a new perspective on what drawing could be. Sculpture not only perfected his drawings; but drawings such as these helped him to push his sculpture to new heights. In the process of planning, preparing, carving, building, and completing a figure or a head, Rodin drew. In the current exhibition he uses blacks and gray washes, thin lines, and limited open white spaces. Rodin conveys powerful tension in each figure or between figures.

The human form occupies much of each drawing. Put into a tight space, almost reaching the paper’s edge, figures seem to exert all their strength attempting to release themselves from an imposed bondage. Capturing the fluidity of the human body, first in clay or stone, to become bronze, shadows are inevitable as changing light bounces off solid mass. Rodin masterfully transfers sculptural elements to the graphic — solid heft in three-dimensions became a two-dimensional drawing of line and shape. The sculptor had an uncanny ability to also work with the nature of non-dimensionality, to take what can be touched to convey the ephemeral, namely light and atmosphere. Beyond subtlety of effect, this element adds hidden qualities of the human soul.

From the exhibition, we derive a more intimate view of Rodin’s personal philosophy, work process, and genius. We see how Rodin struggled within himself to convey essential truths, as he sought to portray humanity through the perfection of the human being and the human body. His people are partially clothed or nude; graceful yet scrawny; or downtrodden yet heroic. In both his sculptures and drawings, Rodin attempted to come to grips with conflicts within himself, his profound sense of freedom and his innate view of human goodness, in contrast to the prevailing morality of the day — God punishes and people suffer in this world in order to enter an eternal existence in the afterlife.

Together the City of Los Angeles and the Los Angeles Department of Cultural Affairs, along with the City of Bordeaux and the Muse͑e Goupil celebrate that Bordeaux has now become the 50th Sister City of Los Angeles This remarkable exhibition should please many.