In our collective onward march toward cyborg-hood, we're fetishizing technology's impulses toward interactivity and customization. Even as we're increasingly regulated by digital technologies, we've become control freaks – and this control mania extends to our artistic experiences as well. The Internet radio network known as Pandora customizes our musical predilections, effectively giving us our own personal radio station. On our laptops, we set our screensavers and desktop images and delimit our preferred speeds of responsiveness for tapping and scrolling. Our smartphones are a smorgasbord of customizable images and sounds, while our automobiles remember our preferences for lumbar support and temperature. The iPhone 5C gives owners the pick of 30 different color permutations. TiVo and DVR allow us to record programs and watch them whenever we want. And indeed, there is the entire phenomenon of the "app" centers facilitating our access to information built around personal peccadilloes.

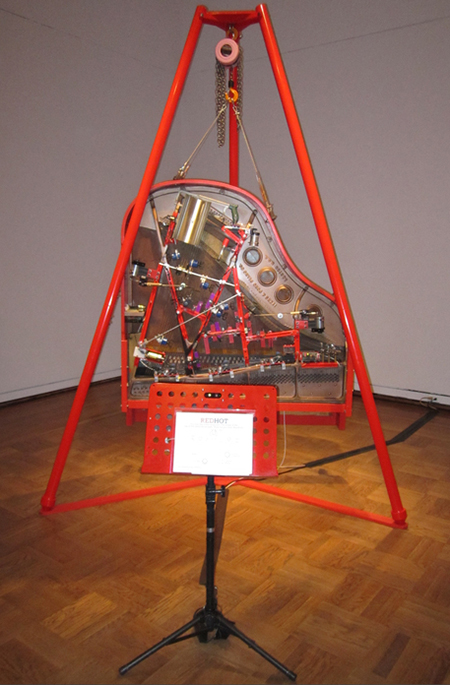

As we increasingly presume that technology will spoon-feed us the exact product of our desires, this feeling of entitlement bleeds over into the way we experience art. Here in the Northwest, a Seattle-based artist who goes by the single moniker "Trimpin" took home a $10,000 prize at last year's iteration of Portland Art Museum's biennial Contemporary Northwest Art Awards. A big reason he got the cash was the irresistible interactivity of the piece he contributed to the exhibition, a modified grand piano called "Red Hot." Whenever viewers waved their arms around in front of the piece in accordance with an illustrated diagram, the artwork would "respond" by plucking, scraping, and otherwise mauling the instrument's innards. Viewers received the gratification of dictating what the piece would do.

A similar phenomenon on the international front came courtesy of Random International's "Rain Room" at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City – quite literally an immersive installation in which viewers walked through a simulated rainshower without getting wet. The piece, as MoMA's press materials explained, "offers visitors the experience of controlling the rain … encouraging people to become performers on an unexpected stage." In late 2012 and early 2013, Ann Hamilton filled the Park Avenue Armory with another interactive installation, the art of a thread: an enormous white curtain strung up with pulleys that rose and plunged in response to viewers-cum-participants going back and forth on swings. The work, as The Armory's website touted it, was designed to "invite visitors to connect to the action of each other and the work itself." And last year at James Turrell's retrospective at LACMA, viewers were personally inserted, one at a time, into a spherical installation called "Light Reignfall," where they experienced a claustrophobically intimate communion with the piece.

Critic and curator Nicholas Bourriaud predicted this sort of phenomenon, termed "Relational Aesthetics," in his 1998 book of that title, while today's curators take it as a given. Earlier this year, MoMA curator Paola Antonelli told The Atlantic that museums had to become more "participatory" and deliver viewers the experience of "a kind of polytheism – you know, you make your own gods." To stay relevant, she concluded, museums "really have to help people do their own form of art."