Continuing through January 19, 2015

“Home and Away” celebrates the two-month fellowship that Japanese-American artist Ruth Asawa spent at the Tamarind Lithography Workshop in Los Angeles in 1965. Despite the brevity of her time at the Workshop, founded in 1960 by June Wayne as a way to rescue the dying practice of fine art lithography, Asawa had rare and unique to access to all seven printers and produced 54 editions, experimenting with technique, palettes and processes. Twenty-three lithographs serve as the subject for “Home and Away,” organized by Assistant Curator Melody Rod-ari. While Asawa is most recognized for her crochet wired sculptures and public fountains in her native San Francisco, her printed works are more than a chapter in the rich narrative of a pioneering artist; they are testament to Asawa’s belief that family and art making are bound by a single thread.

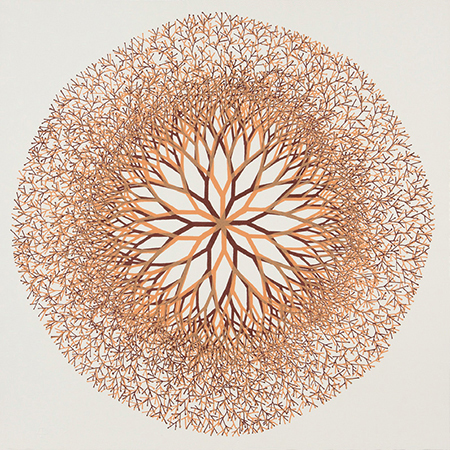

Many of her prints were fueled by a love of family, as a way to connect with them when the artist was away from home. Asawa arrived at Tamarind with sketchbooks filled with photographs of her six children and parents, as well as sketches and watercolors inspired by the flora in her own garden. The lithograph is a medium rich in texture and dense in uncertainty. The delicacy of the medium eloquently reflects the fleeting nature of her subjects — aging parents, growing children and flowers in various stages of life. The medium speaks to human frailty and makes it possible for Asawa to capture the delicacy of ephemeral petals that possess a perennial fascination.

Inspired by a photograph taken by Imogen Cunningham, “Umakichi” depicts Asawa’s father in three different “states.” While each print uses the same image, a bust shot of a balding man with softened features and a floral amulet draped around his neck, the reversal technique is used to brighten and obscure the man’s face. In the first state the face is fully exposed, as if illuminated by a flash bulb, revealing a pair of youthful eyes and a closed smile. The colors in the second state are reversed and the black ink obscures the visage so that it becomes saturated in a melancholic veil, an allusion to his ailing health.

Asawa’s eldest daughter Aiko is the subject of another lithograph, also based on a photograph taken before the artist departed for Tamarind. Working with printer Kinji Akagawa, Asawa achieved a rich texture and tonality in what is otherwise a simple composition, her daughter in profile. While little detail is supplied in the imagery, the balance of bleeding ink and fine lines translate into a portrait of a stoic and maturing girl. Like “Umakichi,” “Aiko” was printed using a single stone but captures a complexity between the bleeding ink used for the hair and the delicate lines used to represent the lace around the handkerchief worn over her head. The lithograph feels more like a watercolor than a print and speaks to Asawa’s ability to command the medium with palpable ease.

This collection of Asawa’s lithographs is indeed part of the larger story of Tamarind’s achievement to preserve an important tradition of printmaking. But these prints, produced during that brief period in 1965, also prove Asawa’s thesis that no matter where we are, whether it’s “home” or “away,” we are never absent from that which makes us whole.

Published courtesy of ArtSceneCal ©2014