Continuing through April 5, 2015

Now that we have left behind that era of art called “contemporary,” or the art of the post-war period, it is about time to contemplate the twilight of the aging contemporary art stars and take note of how their work has matured. Chuck Close has built an extensive and deep oeuvre built on a small idea writ large: the modern face. I use the word “face” so as to stress that the word “portrait” is not the precise term for what it is that Close actually does. A lazy analysis would slouch towards the portrait, which, properly understood, is a holistic idea of an individual that both idealizes and symbolizes a persona. Close always eschewed the inherent idealism and spirituality of the traditional notion of portraiture and teased out the fact that a face is not a portrait: a face is a physical fact. It can be argued that only through printmaking was Close able to fully realize the concept of the face — the materiality of an object defamiliarized through scale and literally remade by the actual hands-on processes that echo the additive process of molding.

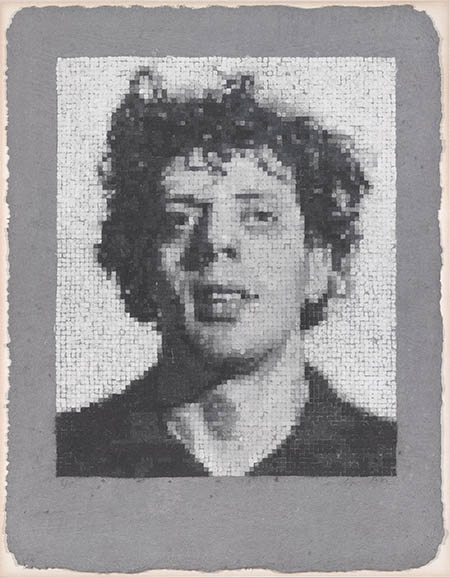

The Schnitzer Collection of Close's prints addresses the paradox of a physical object conveyed in two dimensions through a time-consuming and complex process of manufacture. Close can be perhaps better understood as a process artist whose preference for the grid and tolerance for repetitive motions is not unlike that of Eva Hesse. The key to the conceptual play between the double mediation of the photograph of the painted face and the shift to “making a face” is found in “Keith," a giant mezzotint of 1972 on view at Pepperdine. Made in collaboration with Kathan Brown of Crown Point Press in San Francisco, not only was this the artist's first print, it was also the biggest print of its kind at the time. Measuring 52 x 42 inches, the face so big that it had to be printed in pieces — on a grid. Although to a discerning eye, there are imperfect passages around the nose and mouth, problems caused by Close himself, this imposing feat of printmaking set the stage for the rest of the artist’s career.

Thinking of the different instruments that create tones and harmony in music, Close adopted the grid as a motif that allowed him to think of each square as a unique instrument, understanding how different colors act independently up close and in concert from a distance. This highly complex orchestration of parts creating a whole became a necessity after “The Event” that changed his life — a collapse of his spinal artery in 1988 that left Close paralyzed from the neck down — forced him to paint with the brush strapped to his hand. Intellectually he was made ready, through his printmaking experiences, for collaboration with now necessary assistants, for working from very small to very large, and for turning minute marks into big objects. “Alex" (1993) was the first print Close made after his rehab, and this reduction print, made by six assistants who cut away on linoleum blocks, is nearly eighty inches tall. In contrast to the usually placid expressions of Close’s friends, the face of Alex Katz, based on a photograph taken two years earlier, bears an expression of pain and puzzlement. But his niece Emma, smiles out of a complex grid printed as a ukiyo-e woodcut made in collaboration with the Japanese woodcut artist Yasu Shibata.

The grid, which was an unavoidable “flaw” in “Keith," tilted to a diagonal and became a field of dancing colors that in the case of “Emma" took eighteen months to complete. Perhaps the most personal touch is seen in the fingerprint image of Close’s daughter, Georgia, who has been his subject for decades, maturing along with her father. Compared to other fingerprint works, “Georgia" is relatively small, just under three feet tall, but, when one compares the size of the artist’s finger tips to the total face, the sheer magnitude of care needed for the precise angle of touch and the intensity of pressure on surface becomes clear. The familiar face of a young tousled-haired Philip Glass in “Phil" appears in many guises of printmaking techniques, including the painstaking paper pulp process. A print of this size, almost six feet high, takes no less than six hours of labor by half a dozen assistants who literally build a layered print, made from liquid pulp, which dries and solidifies into a face. Far more animated than the group of impassive and stoic self-portraits would suggest, Close makes work with wit, defying the anachronistic look of digital pixels, not to mention with a refutation of Warhol’s use of printmaking as indifference — these prints are made by hand and with a personal touch.

Published courtesy of ArtSceneCal ©2015