Printmaking and comics—both have suffered the scorn of artists and the public alike. There was a time when artists, curators and collectors alike looked at prints as the province of “dull, pipe-smoking, corduroy, deep type artisans,” as artist Larry Rivers once described it. And comic books were nearly wiped out in the 1940s thanks to conservative proselytizers, such as Fredric Wertham, a well-known psychiatrist who told a senate subcommittee that they “contribute to juvenile delinquency.”

Raymond Pettibon is the progeny of that history, and in fact, may embody its paradoxes and attributes better than most. He claims that he never read many comic books as a child and still “has trouble” reading them now. Yet, as he points out, “my style is based on reproduction somewhat, even when it’s illustration style or etching,” says the 52 year-old. “And I like using [a comic book style], but more as a model than anything else.”

That has resulted in a formal approach that is now instantly recognizable—the simple, almost awkward line drawings, the sordid, erotic, comi-tragic situations, and the outright collision between high-and-low, figurative and non-figurative, and obsessiveness and detachment. To pick two examples out of thousands: a man lies in bed clutching a woman twice his size. He says, “I had to watch her grow and grow while I stayed the same.” In another a scrawny figure floats in a yellow field with blood oozing from his ribcage. The caption reads, “The discussion of the imagination as metaphysics has led us off a little to one side.”

“I don’t know about my skill,” says Pettibon, who has won the Whitney Biennial Award, and received solo shows at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, MoCA North Miami, MACBA in Barcelona and the Whitney in New York. “The drawings can still be pretty clumsy, but in a way I’m fine with that.”

In person, Pettibon could easily double for one of his own characters. Born in Tucson, Arizona in 1957, he stands over 6’ 3” tall with a bear-like frame and faint Irish features. Those who know him say that he’s a gentle soul who wouldn’t think twice about giving you the shirt off his back. Yet at the same time, he wears the unmistakable stamp of a loner—all self-conscious mannerisms, diverting eyes and disheveled looks. In fact, his introversion is so pronounced that it often leads to extreme digressions and fractured thoughts—if only because his mind races faster than he can speak. Take this typical retort: “In relation to comics or cartoons or illustration… I’m taking it more from… that medium or style… my way of communicating… I don’t know… as a given… yet you can still mess with it and uh… you know… we’re all basically using the same typewriters.”

He lives in a three-bedroom surf shack a few blocks from the beach in Venice, which is so unkempt it’s almost laughable. Like the mismatched furniture, each wall seems to have a different color and some are covered in the sort of scribblings you might find in a men’s room—paint splatters, naked women, and graphic phrases like “I’m a bitch baby mama.” Boxes of baseball bats, tennis rackets and baseballs stand in the doorway, as if they were purchased on a whim, brought home and quickly forgotten.

But it’s the sheer volume of books that seem to command the most attention. Not first editions mind you, or even art books for that matter, but thousands upon thousands of cheap paperbacks, whether it’s Philip K. Dick, Karl Popper or Mickey Spillane. “Take anything that you like,” he says matter-of-factly. “Or I could give you a box if you want.”

Given such chaos it’s hardly surprising that he prefers to work en masse rather than on individual drawings. Today his best work often takes the form of an installation, which can either be in a strict linear form where one drawing leads to the next, or in a collage effect, with hundreds of drawings shown all at once. For him, the idea of leap-frogging from one image to another is much closer to the way the mind works, which of course could be construed as an autobiographical impulse. “There is a very fractured personality [in my work],” says Pettibon. “Or sometimes multiple personalities.”

“If Pettibon weren’t as great a writer and reader as he is an artist,” writes Bruce Hainley, “all of this would fail.” Indeed it would be difficult to name another artist of his generation who’s equally conversant in the Scythian wastes of authors like John Ruskin, Gaius Valerius Catullus and Saint John the Divine as he is. But he actually reads those authors—and far more.

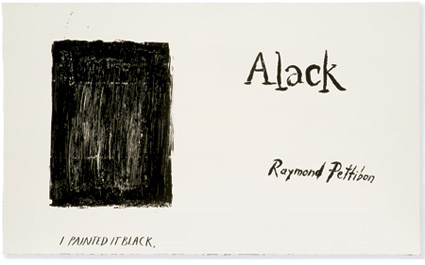

Nowhere is that more apparent than in his latest book project with Hamilton Press. It’s called “Alack,” which Pettibon says is a variation on the word ‘alas.’ (“But with more resignation,” he adds.) It will be printed in an edition of 20, and will feature 25 “appropriations” by Pettibon, meaning each page features a page of text torn from great essayists from the past, including Honoré de Balzac, Paul Gustave Doré, Pliny the Elder, Henri-Benjamin Constant de Rebecque. As is typical of Pettibon, he also added a caption or line of text, which works in concert with the subject matter. And that subject matter tends to revolve around the notion of darkness—whether directly or indirectly. John Ruskin’s art criticism circa 1850 for example, includes a glossary defining “blackness,” while on another page Pettibon features a page of notation concerning Geraldo Rivera’s sensationalist TV show, “The Mystery of Al Capone’s Vaults.”

Yet little of that is legible since Pettibon has blacked out most of the pages with an inky wash. “I actually had mixed feelings about putting these washes over the text,” says Ed Hamilton, one of the legends of LA printmaking. “I wasn’t sure about covering up something that I thought was so beautiful in the first place.”

Perhaps it’s a fitting image for our time: the black-washing of the past and the widespread denial of the world’s thornier issues by today’s youth. But Pettibon claims he started the project “years ago,” with very specific inspirations. One was the black paintings of Ad Reinhardt (who also did cartoons on the side) and the other was a pair of religious texts, one by St. John of the Cross and the other called “The Cloud of Unknowing” by an unknown Christian Mystic from the 14th century. “They’re basically about the idea that a good Christian should [embrace] this dark cloud that exists between the worldly and the spiritual,” explains Pettibon.

Darkness of course, has always been an integral part of Pettibon’s aesthetic, ever since he was the political cartoonist for UCLA’s Daily Bruin in the 1970s. His early work in particular, was full of suicidal women, deviant pederasts, blood thirsty Manson-ites and leather-loving Nazis. Many have attributed that to his relationship to LA’s early punk rock scene (his brother Greg, was the founding member of Black Flag and SST records, and Pettibon provided album covers, graphics, flyers and posters for dozens of bands.) But Pettibon has always been vociferously derisive of punk, especially in his drawings, which usually portray scenesters as pathetic losers. That’s partly because Pettibon believes that any type of groupthink, whether its punk rock or frat boys, is something to be avoided.

Yet if there’s still a dose of misanthropy in his art, which there is, it’s perhaps due to his love of early pulp/noir traditions, as well as his own healthy cynicism. Spend any time at all with him and you’ll come to know a devout recalcitrant who accepts the knottier vexations of American life—with its paradoxical corruption and stupidity. That doesn’t mean he illustrates his chest thumping with overt

messages, as so many political cartoonists do. But rather, he sees his role as a documentarian of sorts, letting his characters embody the most difficult travails of life without sermonizing. “I work more in the vein of the Roman satirists like Horace or Catullus,” he recently said. “They would name names just to put it on record, that this is how things were.”

That can also lead to some utterly touching, quiet, achingly beautiful moments now and then. In fact, many collectors prefer to seek out his images drawn in the mid-to-late 1980s, when he was first realizing some of his most prevalent themes, such as surfers, trains, baseball players, cold war espionage, and economic themes (the latter has been sorely overlooked in studies of his work). Such images tend to forgo histrionics in favor of a more delicate touch, which is also true of both, his recent themes dealing with nature, the human body and the planet, and his recent work on “Alack.”

More importantly, it’s Pettibon’s love of books that remains at the heart of his aesthetic. That makes him increasingly rare in a world defined by electronic media. As he admits, he’s a “better writer than anything else.” Ultimately, he aims for a poetic quality in his work that might be closer to the metaphoric or elliptical quality he often finds in great literature. “That’s my favorite work,” he reflects, “when there’s a poetic, or at least a lyrical, quality to it.”

This article was written for and published in art ltd. magazine ![]()