Continuing through March 28, 2015

“Joseph Goldberg: Sky and Stone — Encaustic Paintings and Sculpture” affords new viewers a chance to see a great artist in our midst and long-term admirers a confrontation with memory, déjà vu and artistic achievement of the highest order. Just as good as Agnes Martin or Robert Ryman, Goldberg, a reclusive painter who lives in a desert shack in remote eastern Washington, is completely unknown outside the region. These deceptively simple oil-and-wax paintings must be viewed up close, giving them plenty of time to soak in. The effort is well worth it.

Now 67, Goldberg is one of the only Northwest artists to be closely associated with contemporary poets and critics, loosely known as the Roethke School (named for the University of Washington professor, Pulitzer-prizewinning poet and certified mental patient, Theodore Roethke), all of whom avidly followed the young painter’s mysteriously beautiful work and saw affinities to their own: nature as subject; artist as shaman or intermediary; emphasis on and tolerance of bizarre and irrational behavior in others; and finally, a garrulous solitude that appreciated writers as artists and, in his early years, artists as writers who occasionally wrote poetry — and kept diaries.

The vast empty, gleaming space within the jagged, irregular edges of each painting has its own topography, tint and, as often noted, mineralogical or “jeweled” overtones. (“Jeweled Earth” was the title of Goldberg’s 2007 Museum of Northwest Art monograph by another poet, Nathan Kernan.) The artist, who grew up on a ranch near Spokane, Washington, discovered indigenous petroglyphs as a child; he did not need to be led to them by Washington State University archaeology students, as Clyfford Still did 30 years earlier in those same caves. Both artists borrowed the Native American aspiration for transcendence and grafted it onto the viewing experience of a painting, constructed, intervened by and made possible by the artist and his magic wand.

In Goldberg’s case, the magic wand is the blowtorch that burnishes the encaustics stretched over Belgian linen. Long before it became wildly popular as a focus for well-meaning hobbyists, Goldberg pioneered Jasper Johns’ and others’ breakthroughs to a much quieter and spiritual end. From a purely tactile and chromatic, optical standpoint, the paintings defy photo-reproduction altogether — another reason Goldberg is still unknown east of Spokane or Boise.

All the same, I would say the “Sky” and “Stone” series are well worth the visit: deeply satisfying, if with few surprises; impressively austere; but still puzzling after all these years. This is Goldberg’s most conceptually cohesive show ever and much of the credit must go to Kucera for his example of severe, reductive taste. He’s done his best to turn Goldberg into a minimalist when even Kernan, the New York poet, considered him better aligned to post-minimalists such as Eva Hesse and Pat Steir — which in itself was a preposterous stretch.

The “Sky” paintings are all the same but each a different color and shape. Fusing drawing (the ragged edge, like a piece of paper) and painting (the taut but liquid surfaces), these are almost more sculpture than painting. The gallery's white-cube lighting tends to flatten the works, which literally change color in natural daylight over the course of the day.

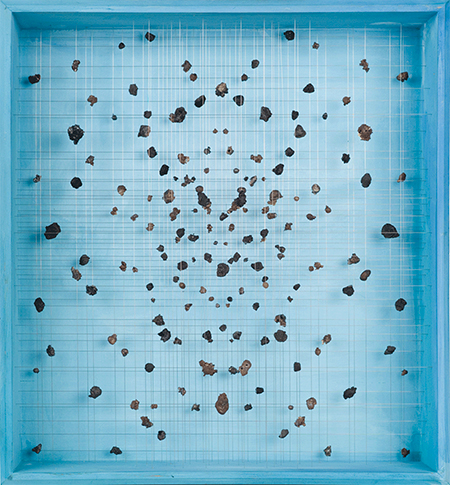

The sculptures that became drawings, the “Stone” series, are a surprising redux of works from 1973, done at the age of 26. “Entanglement,” “Cluster,” “Moth” and “Adrift” (2011-14) affix tiny “coke cinders” to grids of stainless steel wire, like miniature examples of 1970s artists Agam or Harry Bertoia. The containing boxes seem approximately two inches wider and taller than before, averaging 12 to 20 inches high. Otherwise, they are a revisiting of an idea definitely worth resuscitating. More than the self-effacing, subtle depths of the encaustics, with the boxes, one is acutely aware of the meticulous assembly, concentration and craft required. They repay visual attention with strange pleasures.

So is Goldberg the last living Northwest “mystic” or outsider genius of geometric, Kucerian minimalism? On the one hand, how he can make such intense labor and construction disappear into the hint of a midnight summer sky is astonishing. On the other hand, the highly expressionistic systematizing of the boxes suggests Goldberg is coming back to earth to connect with another side of his talent: cool and diagrammatic, periodically emitting an intangible kind of crystalline light. So how about neither and both?