In my last column, I began identifying abstract artists active in the 20th century who had the ability to create work that can potentially engage viewers in meaningful ways, something which much of the current formulaic art known as Zombie Abstraction fails to do. In citing the abstract and semi-abstract AIDS memorial paintings by Ross Bleckner, I was pleased to credit a socially concerned artist who manipulates paint and image skillfully while producing convincingly emotive works.

Another avenue for building relationships between abstract paintings and those who view them can be observed in the recent revival of optical abstraction. In 2007, in fact, when I was in the formative stages of developing an exhibition on the subject, "Psychedelic: Optical and Visionary Art since the 1960s" (2010), I was both surprised and bedazzled by the amount and range of such work that I encountered at the Miami art fairs. Up to that point, many had still considered the Op Art phenomenon of the 60s to be a passing fad. Yet several of the pioneers, including Richard Anuszkiewicz, Bridget Riley and Julian Stanczak have sustained long and successful careers. All are still producing work that can entrance, uplift and mentally transport anyone who might be open to it. And younger generations of artists have found ways to do so while also incorporating conceptual or emotional vantage points that are largely absent from the more scientifically approached optical works of the 60s. Two boomer generation artists who succeeded magnificently in the 90s in this regard are Fred Tomaselli and Sharon Ellis.

Tomaselli is of course the better known of the two, having achieved considerable and justifiable acclaim for using materials innovatively while introducing a "feel-good" kind of art that exceeds the joy-level of a Matisse. Around 1990 Tomaselli began incorporating hemp (aka marijuana) leaves and pills into his paintings. Inlaying these drug culture materials into wood panels and then coating the surface with resin, the artist created elaborate patterns that yield an allover energy, somewhat akin to that of the riveting swirls in Jackson Pollock's best drip paintings. Many of the early examples resemble celestial visions, with clusters of pills and leaves suggesting constellations. Circular formations look like lit-up Ferris wheels that spin optically before our eyes. In contrast to Bleckner's poignantly somber galaxies of the period, Tomaselli's starry-night vistas are downright celebratory. Engaging empathically in these works can instill euphoric sensations in a viewer and, as the artist himself has often pointed out, one can achieve a virtual high without suffering any of the disorientation or undesirable after-effects that can be brought on by ingesting the drugs used to produce the paintings.

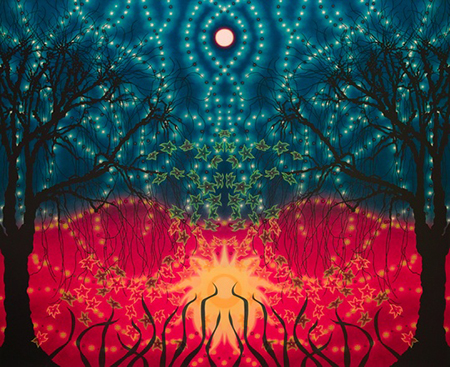

By the mid-90s, Ellis was exhibiting radiant abstract paintings that are inspired by nature but are anything but descriptive. Drawing upon a number of visual language sources, including 60s-era psychedelic posters, Disney films, chaos theory, computer fractals, and Rorschach ink blots, Ellis developed a unique vocabulary for visionary landscapes, one which she has continued to employ over the years. In her earliest works, she would begin by fabricating marbleized paper and then tracing its undulating patterns onto canvas. Next, over a period of several months, she developed her compositions intuitively, applying slow-drying alkyd-based paint, layer upon layer. In the completed paintings, brightly colored monochromatic backgrounds become the staging areas for foregrounds composed of overlapping clusters of nature-inspired patterning. Because alkyd is a synthetic resin, the surfaces of the paintings are pristine and shimmering, which brings a luminous quality to the imagery and makes it all the more compelling.

Another artist who by the late 90s placed high importance on providing captivating experiences for viewers was the late Al Held, who began as a second generation Abstract Expressionist, passed through a minimalist phase, and finally came to explore geometry, first tentatively in black-and-white before concluding that spatial illusionism "is one of the major contributions of Western Culture." By the late 90s, Held had become fascinated with physics, much as Frantiçek Kupka had been decades earlier, but with new information available. Of particular interest to Held were chaos and string theories, from which he surmised that the cosmos is made of many universes that are interconnected and constantly expanding.

In paintings produced towards the turn of the millennium, Held became amazingly inventive, creating mammoth cosmic visions in which complex structures are networked within non-gravitational multi-directional spaces. In examples such as "Aperture III" (1997), Held offers viewers a lot to engage in and discover. With several points of entrance into his hypothetical universe, as well as numerous pathways along which our eyes can travel, we are invited to journey along or through the painting's many corridors, leading us towards a vista of radiant light, far off in the distance.

[Part 3 of this essay will appear in June—Ed.]