“The only thing that is constant is change.” So said Heraclitus, some 2,500 years ago, and not much has happened since to, well, change the wisdom of his observation. Sometimes things seem to change all at once, but most of the time it’s a slow process that sneaks up on us, it accretes little by little instead of in a striking flash. There are more important things in the world that are changing than this, but it’s intriguing that we may be at the cusp of great change in the signature system of the presentation of contemporary art that has held sway for the past fifty years or more. That is the gallery exhibition model, the “one-person show,” where an artist spends months, sometimes a year or more, in the preparation of a body of new work that is debuted at an art gallery, where it is offered for public view and sale. That exhibition has an opening that may be publicly advertised; the artist is usually present; and the exhibition remains up for about a month, to be replaced by the next artist represented by that gallery.

This model still very much exists; you need only look to the right of this column and elsewhere in VAS to see a group of such exhibitions advertised, listed, or being assessed by art critics. It’s still the dominant format, but intriguing fissures are beginning to appear within it, and its unquestioned sway is starting to erode. If I might personalize this, for many years the opening of the gallery season in Chicago, which took place on the first or second Friday of September, was the single most important date of the art year. By July I would be preparing a list of the 40-50 shows that were opening on, say, September 8, to distribute to my students on the first day of class. Galleries would show one of their most important artists in September, and when opening night rolled around thousands of art aficionados would descend on River North or the West Loop (the two neighborhoods with Chicago’s largest concentration of art galleries). Buses would bring in art students from places like Milwaukee, Champaign and Bloomington, and from 4 until around 10 pm the streets of the gallery districts would be packed with roaming bands of art enthusiasts ready for one more plastic cup of white wine, one more trek up a staircase to see — if you could see anything through the crowd — an artist’s intriguing new work. You’d run into old friends and pal around with new ones. The streets were an open-air convention, and you felt you were part of a community. It was exhilarating.

But that’s largely over. There will be no mega-opening night this year. I stopped circulating that list to my students three or four years ago. There will be openings, of course, but fewer, with less emphasis on them, and less an attempt by our art dealers to coordinate them. It won’t feel particularly different than when exhibitions open in April. Why? What does it mean? Why do I have conversations with dealers and (sometimes former dealers) who tell me having a brick and mortar gallery may not be necessary any more, that if you can get into three or four good art fairs a year and have an excellent website and maybe a desk in an office somewhere, you can do as much business as you did in a ‘real’ gallery without the crushing weight of a salaried staff, rent, unending expenses (that white wine isn’t free). Depending on foot traffic it’s the least efficient way of growing a gallery's business. Why do dealers who still have brick and mortar spaces tell me they are doing more than 75% of their business out of town, solely from their websites and connections made at art fairs? Why are they having fewer exhibitions at their galleries, leaving them up longer, and having them feel lax and somewhat of an afterthought?

I’m a long way from declaring the death of the gallery system. It’s doing exactly what it should be doing, it’s adapting to new technology, new collecting patterns, new demands by its audiences. It’s not dying, it’s changing. But I don’t know into what, we’ll find that out together. One of the reasons it’s still relevant is that artists like it, they enjoy having an exhibition, seeing their name in an ad, having their chums show up, it’s exciting to stand in the midst of your work and accept congratulations for a couple of hours. Without exhibitions there can be no reviews, or at least not as I understand them. While dealers may not care that much about reviews (I’ve had many tell me the only part that matters to them is the image accompanying it), artists do and some who have seen their galleries drift toward being fully virtual have moved on to other and sometime auxiliary representation. We’ll see. But it’s out there, and you can smell the fear — is the brick and mortar art gallery akin to the brick and mortar small independent bookstore, already an endangered species?

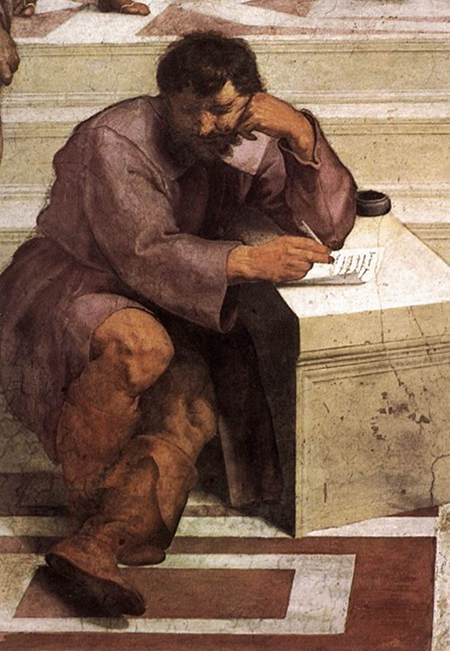

Heraclitus is always represented as the weeping philosopher. I like to think his tears are rooted in his conviction that nothing is eternal, nothing is stable, reality is not fixed, and this is always becoming that. It’s easier sometimes to wail about what is being changed, to see that only as something being lost, than to see the merits of what is coming in its stead. Change, like evolution, is sometimes violent and messy, with both winners and losers. I thought the gallery system, the business of a skilled professional who on site represented artists in the open marketplace of commerce and ideas (though almost every word among those last dozen or so needs to be qualified), was a constant and eternal aspect of visual art. I should have known better.