It is great to see that John Baldessari has received the National Medal of Arts. He did, after all, play a huge role in shaping a generation of artists who appropriate and recontextualize media derived photographic imagery, which is today widely practiced. But, while Baldessari is an acknowledged pioneer in this area, there is another artist who justifiably deserves a posthumous Medal of Arts for using such imagery in a manner that I see as being both impactful and profound. That artist, a contemporary of Baldessari, is Wallace Berman, who tragically died in a car accident on his 50th birthday in 1976.

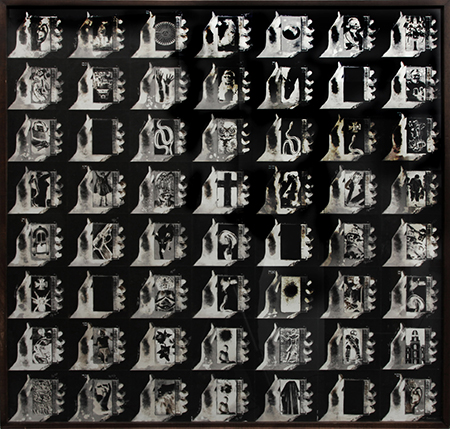

Berman is today generally credited with being a key figure in the birth of California assemblage and a guru to the Beat Generation. I would like to see a medal awarded to him, however, for his Verifax collages of the 1960s and 70s, which many consider to be his most important body of work. Not only were the Verifax collages innovative in their day, but they continue to hold our attention (a few were recently included in summer group exhibitions at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and Michael Kohn Gallery). More importantly, the Verifax collages were incredibly forward looking — even prophetic — in their precursory usage of the visual language that has become the ubiquitous communications standard for 21st century life. Well ahead of his time by almost a half-century, Berman employed a grid structure in his Verifax collages that compartmentalizes emblematic imagery, a prototype of sorts for what is now a common feature of computers, phones, tablets, and televisions.

In the early 1960s, at around the same time that artists such as Andy Warhol and Robert Rauschenberg were experimenting with screen-printing, Berman began using a now obsolete photocopy machine, the Verifax copier, to replicate photographic images that he could print and organize into modular grids. Unlike the Xerox copier that supplanted it, the Verifax version had the capability of producing images from negatives in addition to positives (which today is easily done to photographic images digitally using Photoshop). Although Berman tried both approaches, printing from negatives afforded him a novel aesthetic opportunity. In that the images resemble X-rays, they convey a quality of spiritual light that was particularly well suited to the artist's interest in mysticism and the Kabala.

Influenced no doubt by the serial imagery of many of his contemporaries (Warhol's soup cans, for example, debuted in 1962 at the Ferus Gallery, where Berman had exhibited in the late 1950s), Berman filled each module of his grids with a repeating image of a human hand holding a transistor radio. On the face of each radio the artist planted a symbolically loaded image culled from the photographic lexicons of everyday life, science and religion. Crosses, dark voids, Indic mandalas, Buddha figures, church facades, the U.S. Capitol Building, the Milky Way, reaching hands, human ears, stop watches, locks and keys, roses, mushrooms, skeletons, coiling snakes and sports and rock-and-roll icons can all be found arranged in varying compositions within each of Berman's grids, accompanied by a random scattering of Hebrew letters that have no specific meaning. According to the Kabala, God created the universe by uttering the Hebrew alphabet, the first letter of which is the Aleph, which Berman wore proudly on the front of his motorcycle helmet.

Berman's incorporation of the transistor radio as a repeating motif in his Verifax collages is particularly significant because, in the 1960s, popular music had become a primary source from which youth received their daily cultural buzz. When viewed within the context of the Beat Generation's search to find spirituality in everyday existence, the collages offered a compelling visual shorthand that could supersede traditional religious scriptures in posing questions about humanity and morality. In his own unique way, Berman created a contemporary bible using pop-culture lingo, thereby making timeless questions accessible to those weaned on popular media. In so doing, he was responsive to a cultural zeitgeist in which color television was brand new and everyone was talking about Marshall McLuhan's "Understanding Media." Like Baldessari, Berman was one the first contemporary artists to communicate in a language that was totally in sync with the new cultural paradigm of the time.

At present we are living in the most rapidly changing time period since that fast-moving decade when Berman introduced the Verifax collages. And this is markedly evident in the radical changes within information technologies. More and more, these advanced systems are using a Berman-like grid for almost every device that provides us with information or entertainment. Yet, while Berman's Verifax collages can stimulate meditations on being or issues of conscience, today's digital devices function as interactive gateways for travel along a seemingly infinite number of pathways. Whereas Berman's imagery seems to say "This is our universe, these are our options," our current electronic media simply announce, "These are your options, pick one.”